In Parts I and II we looked at the movement of Federer and Nadal and how their footwork was a reflection of their game styles. Federer used reactive breaks in his legs perhaps more than any player in history. Nadal used the defensive V with an open stance to play a powerful brand of tennis from deep positions. In Part III we look at Djokovic and how he came to be the poster boy of modern-day court coverage.

One of the interesting things about Djokovic is that he doesn’t garner the same buzz or appeal that Federer or Nadal did. I’ve often thought it’s because Djokovic’s style is the most subtle.

It’s hard to put your finger on exactly why his game doesn’t generate as much excitement or fandom, but I think there are a couple of possible reasons. Firstly, I think his greatest work is often buried within points: instead of an emphatic winner of blazing speed, spin, or court craft, he more often chooses to pick a “bread-and-butter” target that will force an error from his opponent.1 This gives the impression that he makes others play poorly, or is just “making balls”, rather than doing something freakishly good himself. An excerpt from last year’s Tel Aviv Final analysis:

“Corner defense married with controlled depth and subtle change-of-direction may not make for good highlight reels, but it allows him to effortlessly tear apart quality top-20 opposition without getting out of mid-gears.”

Of course, being able to consistently hit forehands and backhands crosscourt and down-the-line in a rote manner at will is ridiculously hard to do—most pros are uncomfortable with at least one of the four shot patterns at the top level—but it’s difficult to appreciate as a casual viewer just how well Novak can play these butterfly patterns.

Second, his court position, shot speed, and overall strategy are also buried between extremes. He doesn’t move forward or take it as early as the most aggressive players, yet he also doesn’t stand as deep as Medvedev or Nadal. He doesn’t hit it particularly hard or heavy, and he doesn’t vary his speed and spins all that much either. Part of this is reflected in the notion that his game trends toward containment rather than creation: he wants to be able to get his opponent’s best shots back without conceding as much ground as Nadal or Medvedev, and he wants to be able to get their best shots back with disciplined interest.

Overall I think his movement plays into this lack of buzz (and I say that in purely relational terms with players like Nadal and Federer. His sliding exploits are highlights themselves).

In Part I, I explained how contradicting lines can draw your attention via contrast and bring harmony to clothing, and I asked the question if the same visual appeal applied to the body in motion. Federer’s scissor kicks and reactive breaks allowed him to hold the baseline and play with linear precision that made him the gliding doyen of tennis; Nadal played powerful, parabolic shots on the defensive V with that iconic uppercut forehand. However, of the Big-3 Djokovic has the least amount of “contradiction” in his movement and style. Especially with his forehand, when you watch Djokovic you will see that he mostly employs an open-stance forehand with a shoulder finish. There’s more of a “sameness” to his stroke and shot type. Everything unwinds in a counter-clockwise fashion: feet, legs, hips, shoulders, racquet, both arms. I once described him as a “revolving door”. The left-arm finish can almost look uncontrolled at times:

But as I’ve said of Medvedev before, what happens to the body after the shot has been struck has no influence on the shot itself.

Shown in isolation in the gif below you can see how everything unwinds counterclockwise—there’s no contrast—and Djokovic manages to jump forward and across as he hits this ball, almost like a skier changing tack.

I can’t help but wonder if, in addition to his sliding, the way he hits these wide-open-stance hop forehands was influenced by his junior days as a skier back in Serbia. Look at how both toes start and finish in sync. An excerpt from Active for Life:

“After watching Djokovic beat Rafael Nadal, uncle Goran Djokovic, himself an accomplished skier, is equally quick to credit Novak’s abilities to his time on the hills, saying, “When he’s sliding on the court, this is like skiing. People say, ‘How is it possible?’ Because of that. It’s simple.”

The foot and leg work are remarkably similar in terms of technique.

And so it may be that Djokovic’s on-court movement was subconsciously influenced by the Serbian slopes:

“After exercising our muscles or our brain in a new way…we can do so no longer at that time; but after a day or two of rest, when we resume the discipline, our increase in skill not seldom surprises us. I have often noticed this in learning a tune; and it has led a German author to say that we learn to swim during the winter and to skate during the summer.”

— William James, The Principles of Psychology

This open-stance forehand has become the norm on tour as Federer’s cross-step became phased out, and I think this reflects an overall trend where the ability to absorb and recover has been rewarded more than the ability to press and attack. Cast your mind back to the ‘V’ patterns Federer and Nadal used well. What I think Djokovic did, was strike a balance between both. By being the best exponent of flexible, wide, open-stanced shots off both wings, coupled with his flatter trajectory, Djokovic was able to play a paradoxical brand of “defensive offense” or “offensive defense”; he was often most dangerous when pushed wide where he could use the opponent’s pace and angle against them, and he was most often tied down and thwarted when starved for pace and height through the middle.

Of course, these are generalizations; all players play on all the V’s, but it’s helpful to apply this brushstroke when discussing the Big-3 and what they trended toward.

And on the topic of generalizations, another aspect that sets Djokovic apart is his relatively agnostic preference for forehands or backhands compared to Fedal, who both looked to venture into their backhand corners more often—and to more extreme degrees—to hit their forehands.

Below is a Hawkeye movement heat map from the 2012 Australian Open final (highlights) between Djokovic and Nadal (Images from Reid and Duffield (2014)).2 I think this showcases how well Djokovic was able to direct his backhand with authority crosscourt or middle into the Ad-side—into Nadal’s forehand!—because Nadal prefers to attack with his forehand when running around his backhand on the deuce side. Nadal’s ability to hit his forehand up-the-line was always a barometer of how well he was playing, and it was an important shot if he wanted to beat Djokovic because it got him out of this holding pattern. This also reveals why Federer had difficulty against Nadal: as a righty with a single-hander, it was hard—too hard, usually—to flatten out his backhand off the Nadal forehand.

If you tease apart the rally data from that match (courtesy of tennisabstract.com) you can see how effective and important the backhand down-the-line was for Djokovic.

Djokovic hits more than twice as many backhands down-the-line and/or inside-out than Nadal.

Djokovic also finds more inside-out forehands than Nadal. This is why a great backhand line is so handy; it opens up a huge amount of forehands for you on the next shot.

In his semifinal win over Federer, Nadal won a whopping 60% of points with the cross-court forehand. Against Djokovic in the final, that stat drops to just 40%!

There’s a trove of other data points you can comb through, but just watching the highlights, you can see how few and far between the inside-out forehand was for Nadal (and when he did find it, he looked far more dangerous), and this is the magic of Djokovic. He can press you in both corners and just do it for hours. He doesn’t let you play your game because he has all four rally balls—forehand and backhand, cross and line—on tap, and this is what allows him to camp closer to the middle.

In more recent slam performances I’ve highlighted how he’s exposed many youngsters early in matches with his off-backhand (vs Alcaraz in Paris, and Tommy Paul and Stefanos Tsitsipas in Australia) against forehand-hungry players.

This “off” backhand, which seems to careen away from the player with unbelievable precision, is perhaps the most underrated, or least discussed, aspect of his game. What he lacked in forehand dynamism from the center he made up for with change-of-direction backhands:

Given the vulnerability of running forehands in general, recently I’ve come to think this off-backhand shot is perhaps the next best thing a player could have after a great forehand.

Of course, no Djokovic movement piece would be complete without mention of his sliding exploits (a phenomenon explored brilliantly by Matt Willis here). The sliding backhand especially is his trademark shot; a combination of speed and flexibility that makes him sponge-like from the corners. I won’t comment on that aspect too much here because Matt did such a thorough job of it, but I like this excerpt (emphasis added):

“This is one of the things that makes Djokovic so superlative when it comes to his ability to slide and move. While a few of the other double-handed backhands like Zverev, Medvedev, Nadal (from 2005-2010) et al can or could slide well to their backhand side on a hard court (certainly better than most single handers at least), Novak’s balance on both forehand and backhand slides is on another level entirely. He can be offensive or defensive from either wing on the full stretch, and his spring loaded recovery thanks to strong but flexible legs negates positional advantage better than anyone. This all contributes to Djokovic being the hardest player to hit through, on a hard court, that has ever lived.”

We’ve seen a generation of players post Big-3 comfortable sliding on forehands and backhands, but as already mentioned, none match Djokovic’s overall level from both sides. The below point showcases two things: (a) How far prime Federer would run around his backhand to hit forehands (to a degree Djokovic never did/does); and (b) Djokovic’s ability to slide and hit with depth and precision on the full-stretch from both wings.

That he wins the above point with a running forehand touches on another theme I’ve been noting (here, here, here, and here) which is Djokovic’s case as possessing one of the all-time great forehands. Names that most often come to mind: Federer, Nadal, del Potro, Gonzalez, and Sampras for starters. Even in today’s crop most talk about Tsitsipas, Thiem, Berrettini, or Alcaraz. All offensive merchants with point-ending power capable of conjuring winners from all parts of the court.

It’s the winner that is memorable to both the fan and statistician.

There is no statistic for “shots made that most other players would have missed”, nor do we measure how effective the depth and pace of a ball is despite not being a winner (although there are stats being made that are very favourable to Djokovic’s case).

But I’d wager Djokovic’s forehand return is more consistent and more deadly than all of those players, he misses less than all of those players, changes direction on the run better, maintains better depth, and is most dangerous when you give him power and angle to use. This subtlety all feeds into his lack of buzz and fandom (again, relative to Nadal and Federer).

With respect to his flexibility, having a greater range of motion in your legs allows you to play open-stance shots at greater speeds and widths, because you can get your outside leg far enough away from you to then push against/slide against and maintain your balance without tipping over.

Evolution of the wide forehand, from top to bottom:

a 1990s Sampras plays a classic running forehand where he hits and keeps running through the shot. A technique I touched on in the Federer movement piece

a 2000s Federer plays an open-stance running forehand with an additional cross-step afterward.

a 2010s Djokovic plays an open-stance hop forehand where he both jumps and lands on the outside leg planted very wide, slides, and then is ready to push back immediately.

Of course, there is also a level above this again where you hit the shot as you enter a full-stretch slide on the right leg from the left leg push:

So while the recipe for being an all-time great has trended toward having a “sword” of a forehand and a “shield” of a backhand, Djokovic has bucked the trend a little, making his forehand more “shield-like”, and his backhand more of a sword, and placing himself closer to the middle of the court. From there, it’s clear that there was less of an “open space” to attack compared to forehand-hungry players, and ironically, by developing a better backhand, he often ends up hitting more forehand winners than his “better” forehand opponents (this was true in the Australian Open final in 2012, for example, but also more recently against Tsitsipas in the Australian Open final this year).3

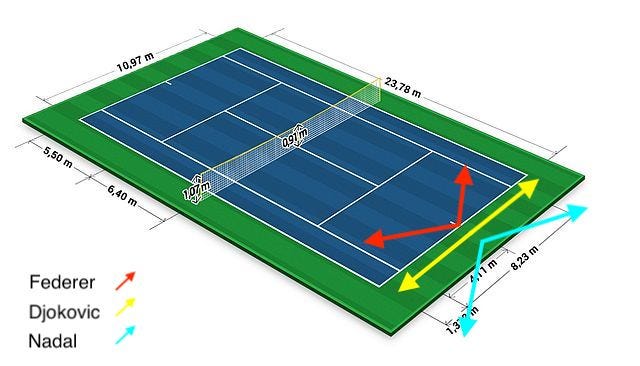

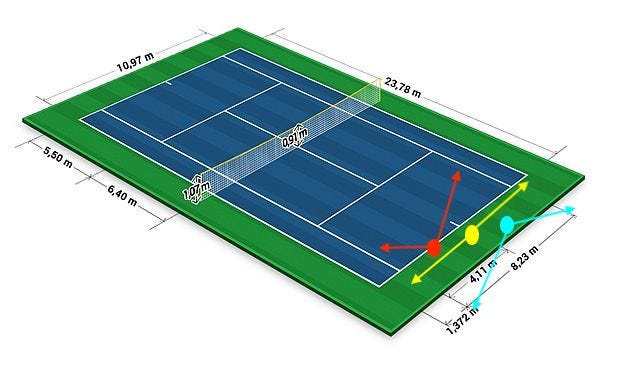

Perhaps it’s a better generalisation if we adjust their maps with their forehand preferences:

Ultimately, each of these three players brought something unique to the game not only with their shots, but with their movement. All-time greats tend to do that. Alcaraz has done something similar again with his “north-south” movement, as I touched on in his Barcelona final win back in April.

I hope you enjoyed the series, and if you have any questions feel free to drop a comment. I’ll be back soon with a piece on lag, or a lack thereof later next week.

Of course he still has a huge body of work showcasing end-range winners, but think more than others (Federer, Nadal, Alcaraz) he doesn’t finish as many points with emphatic displays of forehand power/spin/drop shots etc.

Reid, M., & Duffield, R. (2014). The development of fatigue during match-play tennis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48 Suppl 1, 7–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-093196

This isn’t to say that Djokovic’s backhand hit more winners than his forehand, or that Djokovic preferred to attack with his backhand instead of a forehand. I’m just pointing out that, relative to Federer and Nadal, Djokovic ran around his backhand less, and hit more attacking backhands.

Great analysis as usual, few questions.

1. "This also reveals why Federer had difficulty against Nadal: as a righty with a single-hander, it was hard—too hard, usually—to flatten out his backhand off the Nadal forehand." Will this scenario be an issue for every right-handed one-handed backhand player because where Fed had this issue I don't remember Wawrinka, Blake or Thiem having this problem unless I recalled wrong and if so is this problem of flattening out Nadal's ultra heavy forehand at you towards his forehand always going to be a critical issue for a right-hand one-handed BH player? How could they combat this problem?.

2. Thanks to you and Matt Willis' "Sliderman" you recommended I have come to understand the prominence especially on the backhand side of sliding, recovering and just movement in general and how at it's extremes Novak's displays on his BH can be superlative. However Novak is a wielder of the two-handed backhand, is the stuff he does with his two-handed backhand both technique-wise and movement/recovery/sliding-wise possible to translate to a one-handed backhand? Is anyone doing or did what Novak does with his two-hander with their one-hander on the tour right now or back then and if not how would you direct such a person wishing to nuance their one-hander in such ways?

3. I know from your last piece and you mentioned it here that you are working on the topic of lag/lack thereof and I was wondering if in that piece you would cover the following. Why is it that even if you have a large crop of forehands following the "Ferris wheel" approach you get variations of why some do well on some court surfaces and some not??? Always surprised me after finding your thread and reading "the death of the forehand part 1" for the first time why someone like Wawrinka struggles on the grass but Federer not at all yet Wawrinka exploits the clay and hard courts so much better than Fed could (maybe not hard court but clay court definitely)?. Or why such a large "WTA style" takeback in the hands of Robin Soderling made so much damage on the clay despite a "large takeback" but a shorter compact swing like Fognini's is almost unheard of getting him to the semis or quarters (aside from his 2011 run) in Roland Garros?. Where is the line drawn where the "Ferris wheel" forehand stops becoming an aid with its more quieter swing and less moving parts and now a "personal deviation" is more of the factor that top dogs like Roddick or Sampras consistently made Wimbledon finals where Wawrinka hasn't made one Wimbledon final despite him having a devastating forehand and vice-versa with Roddick and Sampras not ever making Roland Garros final but Wawrinka winning one?. Are Djokovic and Agassi's forehands maybe the best in terms of surface versatility (slam wins on every surface/consistent threat on every surface all the time and not a one-time luck win like Federer Roland Garros 2009) and if so why if they all had the Ferris wheel forehand?.

PS: Are you Zoid from Talk Tennis?.

Hi Hugh,

Wondeful analysis as always and great conclusion to the series overall.

One question to make sure I understood this piece and other ones good. That comparison between Sampras’s, Fed’s and Novak’s footwork reminded me of Alcaraz’s movement between Roland Garros and Wimbledon. At the french (and on outdoor HC for now) from your piece he was looking closer to Fed’s and at Wimb way closer to Nole’s. Given the added moving part that constitutes his inverted head start that can make a cocktail for running FH errors but when he cleaned his footwork that’s when he put on his best performance from that side.

If so, given the fact Djokovic uses it on all courts and it’s becoming a norm, don’t you think Alcaraz would be able to make the change on all surfaces too? That would make his FH the perfect tradeoff and goat in the making imo. Perfect combination of lag and control (with his ferris wheel and extended wrist he already has a deadly combo as unlike shapo’s for example, he can attack and absorb relentlessly unless you REALLY stretch him).

Anyway, even with those small efficiencies (that + the setup on his backhand) I think it ain’t enough to consistently exploit as Wimbledon was a reminder imo. He has 4 great patterns.

PS: Also loved the addition of a meme to illustrate your point. As you said many times, the greats adapt.