The Movement of the Big-3: Part II

buying time—defensive V—backfoot pivots—deceleration

In Part I we looked at some of the unique aspects of Federer’s movement and how it interplayed with his game and overall legacy. In Part II we look at his nemesis: Rafael Nadal.

One of the unique features of tennis is that while the ball must obey the lines of the court, the players can largely operate outside them. Yet, the idea of being aggressive often implies a court position close to, or inside, the lines. McEnroe, Sampras, Agassi, and Federer were all forecourt merchants that excelled at stealing time by stealing meters. The basis of their aggression was as much about their court positioning and weight transfer into the court as it was about their swings and ability to flatten out their shots. From a birds-eye view, attacking was akin to some two-dimensional Pong-like exercise where players strung together a couple of geometrical straight lines, the closer to the net the better.

Nadal completely changed that.1

To understand Nadal we need to find a perspective that gives the viewer an understanding of how his movement was in service to buying time and playing with height and spin. We need a Royal Box seat lower to the court to appreciate this:

From this lower perspective, we can see how Nadal’s vertically inclined game meant his movement was in stark contrast to Federer's. Whereas Federer employed the scissor kick footwork to help him stay aggressive in a time-stealing, linear-hitting fashion, Nadal often used the reverse pivot to help him buy time in service of a parabolic brand of tennis. Note the reverse pivot footwork that he used so often:

All players use the reverse pivot to some degree but it’s not exactly an ideal way of hitting the ball if you want to dictate the rally. However, Nadal was an extreme player in several ways:

He was a physical specimen. Just a pure athlete with python arms. Probably the only player who should have ever worn a tank top on the court. He could just murder the ball for hours on end and, crucially, he was unbelievable from end range (as we will see in later clips).

He was also the fastest kid alive.

This speed could also be used in service to offense. Much like his coach, Carlos Moya, Nadal looked to run around his backhand and dictate the rally with his forehand, even while moving backward. Having this unique property—being able to attack or stay neutral while reversing—opened up a huge number of balls for Nadal to run around. I mean, Kukushkin literally hits this backhand slice into the corner, fading into Nadal’s body, on grass, and Rafa still minces it. I don’t think we will see that shot again in our lifetimes:

He mainly channeled his racquet speed into topspin, rather than pace.

And the real kicker: he was a lefty.

So Nadal was able to take this spin-oriented, defensive-moving version of tennis, dial the racquet-head speed and intensity up to 11, and play like that for hours on end. Even if you taught this style to a player from a young age they would need a monumentally big engine to pull it off.

One of the great points of the Fedal rivalry is the very first one from their 2005 Roland Garros semi-final. This was their first grand slam meeting, and it perfectly encapsulated both their styles and the contrast they brought all within the space of four shots. Federer, trying to step in and pressure Nadal with his serve-plus-one forehand, just had nowhere to hit when Nadal could shoot-to-kill from deep on the run, especially on clay. It was quintessential Federer. It was quintessential Nadal:

I mean, that’s just a ridiculous way to start a grand slam semi-final.

One of the things that made Federer such an effective offensive player was his ability to take the ball early. He could play on the front foot and then employ a huge amount of spin to bring the ball up and down, especially on his forehand (just like in the above point).

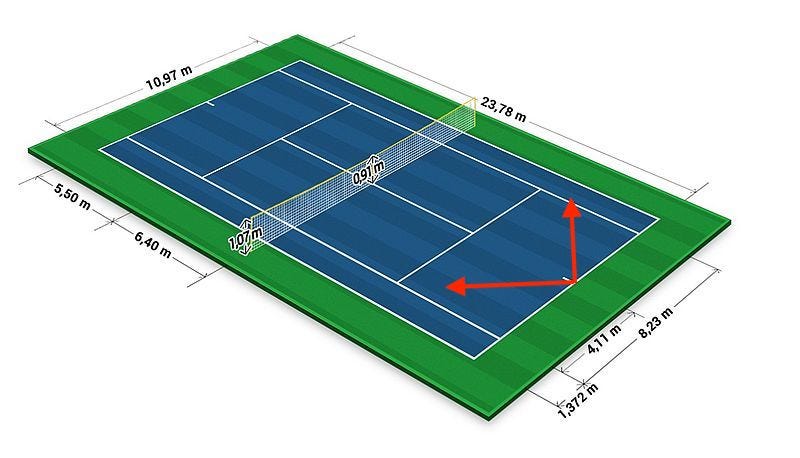

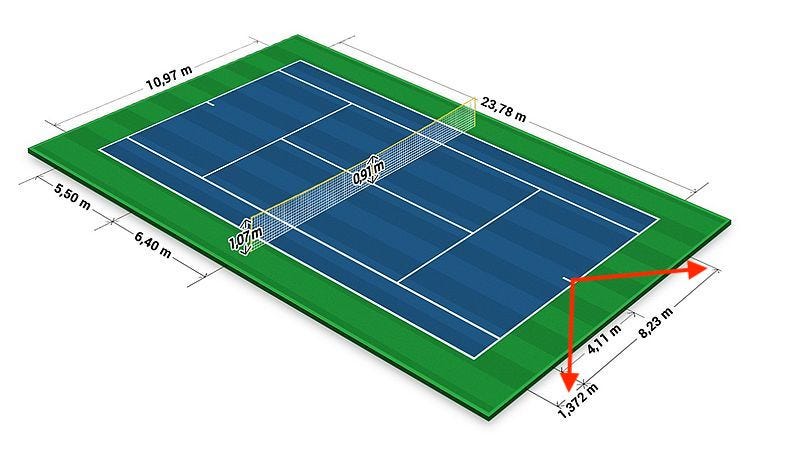

Coaches often talk about moving on an angle to cut the ball off, or moving on a ‘V’ when being aggressive. If you watch the above point again, you can see Federer move on the AD-side of the V to take on that forehand (as well as those scissor kicks we touched on last week):

But what I think Nadal did better than anyone in the history of the game, was play a powerful brand of tennis on the defensive ‘V’:

The defensive V is usually reserved for, well, defense. But Nadal had the ability to generate a huge amount of pace, depth, height, and spin playing on defensive backfoot V patterns:

He was the first player to adopt the super deep return position for hardcourt tennis, one that is now popular among a slew of players (Medvedev, Thiem, Ruud, Alcaraz, and Musetti are good examples). But none can match his danger from the extremities:

And this is really what sets him apart from everyone. He’s the only guy who’s ever been able to end rallies from far-flung corners—whilst moving backward—with incredible pace and spin from both wings. The Nadal-Berdych 2012 Australian Open quarterfinal is some of the best hitting you will ever watch. You’ll see Berdych employ footwork patterns very similar to Federer, but again and again, you’ll witness the defensive V work from Nadal. Here he crosses the centre of the court running over the ‘Melbourne’ sign (~3 metres behind the baseline) and then hits the passing shot from what must be 6 metres back.

And what you’ll also notice is that Nadal often uses the outside leg when playing defense (unless on a dead sprint).

And it wasn’t just the forehand. Nadal’s backhand also packed heat, again, from the outside leg in the below example:

That outside leg is crucial because it allows a player to decelerate quicker.

Deceleration

Almost no one talks of deceleration. It’s not sexy. Speed, spin, and power are what it’s all about. The more the merrier. This is what NFL combines measure, but pay less attention to braking:

“Barry Sanders, arguably the best running back in the history of the game, was renowned for his ability to stop and go at unreal rates. Ed Reed, an NFL Hall of Fame safety, could break on the ball in less than 200 milliseconds out of his backpedal, giving him the advantage over the QB due to his elite deceleration capabilities.”

— Joey Guarascio, Understanding How Simple Biomechanics Points Toward Eccentric Training

Nadal (and Djokovic) brought Sanders-esque braking to tennis; they could sprint to the ball, take a giant lunge with the outside leg, hit the ball, and then push off that outside leg and recover. For an in-depth read on the evolution of hardcourt/grasscourt sliding in tennis, Matt Willis of

wrote a great piece titled ‘Sliderman’. Here is a short clip of Nadal from his YouTube channel that highlights how the outside leg slide allowed for extremely quick recoveries:Haas steps in and hits into the corners, but by the time he was ready to hit the next shot, Nadal was almost in the middle of the court again having played an open stance sliding forehand.

And to make matters worse for his opponents, Nadal’s backward leaning and open stance movement meant he could employ more height than most when playing defense. This extra height bought him more time to recover, further stifling his opponents’ chances to build on their attacking shots. Here he uses an extra high and heavy ball to turn defense into attack one ball later:

I don’t think this brand of tennis is possible to grasp without looking under the hood and analyzing Nadal’s racquet.

Racquets

I’ve written before on how swings and racquets influence tactics and court position in a piece called Tradeoffs. Below is an image from a brilliant dataset from Stephanie Kovalchik’s website (www.on-the-t.com) from 2018 to 2020 ATP matches. Compare the first and second-serve return contact points of Federer (green) and Nadal (orange) on hard courts2:

You can see Nadal opts to take a deeper position compared to Federer. Nadal liked having the extra time to really take a big cut at the ball, and he could generate a lot of topspin to either hit it back high (which would buy him time to recover) or hit a dipping angle if a player tried to move forward on him. But it’s less that he liked having extra time as much as it is that he needed the extra time.

Nadal certainly has a pretty “extreme” racquet setup. An excerpt from tradeoffs:

Nadal also uses a relatively heady-heavy and high swingweight racquet, however his lead placement is far more “polarized”; the extra weight is placed at the extremes, in the handle and under the bumperguard. He also uses a much smaller grip that allows him to use his wrist more, and he uses a more open string pattern with a full bed of stiff polyester string. The small grip, open string pattern, and “hammer-like” weight distribution of his racquet is set up for spin (obviously). Taking the ball flat and early is harder by design. Of course he can still do it because he’s Rafa, but he was always facing an uphill battle on a hard or grass court without much life (bounce) in it against Djokovic.

You can actually buy something close to Nadal’s specs (allegedly) from TennisWarehouse. Their description:

What defines the Rafa Origin, however, is its 365+ RDC swingweight, making it very challenging to swing but giving it the needed heft to absorb and redirect the highest levels of pace. The high swingweight offers massive plow through power which is perfect for hitting punishing groundstrokes and serves. The flip side is that ripping heavy spin-loaded angles like Rafa takes additional care with both timing and technique. Those who can leverage this racquet's mass will find dangerous levels of pace from the baseline and rock solid stability at net.

So the bloke used a battle axe with a tiny handle. It was harder to get going compared to Federer’s (relatively) lighter scalpel. But standing deeper and moving back as he chased down balls bought him enough time. Below is one of Fedal’s most iconic points. This pass would bring up match point for Nadal in the fourth set tie-breaker from their 2008 Wimbledon classic (Federer then hits his own amazing backhand pass to save match point and eventually force a fifth set):

And if you’ve read last week’s piece on Federer you can now attend to both their footwork and see the contrast so clearly: Nadal on the open-stance defensive V taking huge cuts at the ball, Federer on the attacking V coming forward. It’s why watching their rivalry was so great; not only did they both bring an incredible overall level, but they did so with such contrast in their swings, movement, and tactics. Below is probably their most famous rally. Again, note the difference in baseline position and the types of stances employed.3

While Nadal has found success at all the Majors on multiple occasions, it was on clay where these qualities of his game were magnified, making him virtually unbeatable. If there has ever been an Everest challenge in tennis, it is without question Rafael Nadal at Roland Garros. Almagro’s prediction was not far off4:

I feel pretty confident saying Nadal’s clay feats will never be eclipsed in my lifetime, and I don’t think anyone will dominate a tournament like Nadal dominated RG.

That fall-away lasso forehand with the bicep is part of Nadal’s legacy; his style was every bit as exciting and unique as Federer’s.

However, on the tennis court, the Spaniard met his match when Djokovic came into his own in 2011.

In Part III next week, we look at Djokovic’s movement and how it helped him dominate the game for the last decade.

Federer did use a lot of spin himself to attack, but not to the same degree as Nadal.

You can read that piece to see how it changed for grass and clay.

Important to mention that Nadal was also incredibly proficient at stepping in and taking the ball inside the baseline, but I’m trying to highlight some of the unique aspects of his movement with these defensive V examples. Nadal’s mindset is definitely offensive; he’s always trying to hurt you with his ball or hit a ball that can generate attacking options for him, but against Federer he more often was playing defense because Federer was one of the most aggressive players on tour.

Nadal at Roland Garros in 2008 was the most dominant slam I’ve ever seen. The scorelines are scary.

I love the idea of the defensive V, and how well Nadal could dictate even from back there. I think Alcaraz, despite having the speed to cover these balls, can’t quite produce shots with the combination of margin and aggression that Nadal could from these positions, which is why I feel like he plays spectacular defensive points that he often loses (though he is getting better here, like at everything else).

Great thoughts Hugh. I remember early in Nadals career, he played Agassi, Agassi said something like I don't know what he is playing out there, but it is not tennis. Other players now get Rafa like rpm's on the forehand, but no one has ever been able to consistently bend the ball around out there to expand the opponents court, east and west, like Nadal. Of course, it is most evident when he hooks his forehand wide into the ad court, I introducing his opponents to part of the court they usually are not at. Of course, he also used his hook to bring the ball back in when he was going down the line. Using a thicker beam high swingweight racquet, he got from Moya. Moya used to play with a more extreme version, a Babolat Soft Drive, leaded up to about a 400 swingweight.