“There are no solutions; there are only tradeoffs.” — Thomas Sowell

One of the most enjoyable aspects of tennis is the variety it can offer in terms of match-ups. McEnroe-Borg (Fire and Ice!), Sampras-Agassi, Nadal-Federer. These rivalries were as much adored for their contrast as they were for their quality. Watching two GOATs clash with different styles, tactics, and temperaments—and across different surfaces—probably satisfies some innate desire to categorize things. It’s part of the reason Fed and Rafa get more love than Djokovic—their styles are a little more salient, and how they win points is a little clearer to casual observers (this isn’t a knock on Djokovic). The iconic ‘Fedal’ exhibition match on a half-clay/half-grass court back in 2007 was a great PR stunt that celebrated their differences as their rivalry grew into something legendary, but tennis generally does a poor job explaining why certain swings/racquet setups/tactics etc. are more suited to certain conditions.

A swing is made up of certain elements that each require a choice, and these choices are tradeoffs. Let’s take the forehand as an example: Eastern, Semi-Western, or Western grip? High take-back or low take-back? Elbow high (a la Lendl, Sampras, and Kyrgios) or lower (Federer, Nadal, and Rune)? How long or short is the takeback? Wrist flexed or extended in the setup? Bent or straight arm on contact? All of these choices come together—usually nudged unconsciously—in to what we see as the player’s swing. Watch enough tennis and you’ll see each one as unique as a fingerprint. Each has it’s advantages and disadvantages. The video below from Top Tennis Training does a good job pointing out each of these subtle differences between Federer’s and Nadal’s forehand technique from the latter part of their careers.

Furthermore, the racquet itself also requires a tradeoff. An excerpt from “Technical Tennis: Racquets, Strings, Balls, Courts, Spin, and Bounce”:

“Hitting a tennis ball is an epic battle between player, racquet, and ball. The player ultimately wants to be able to swing the racquet as fast as possible and to change its direction in a split second, but he does not want the ball to be able to do the same thing to the racquet. He doesn’t want the ball pushing the racquet backwards, twisting it in his hand, or bending it out of shape and direction. But making it more difficult for the ball to move the racquet also makes it more difficult for the player to do so. For the player to achieve the most maneuverability, the racquet has to be light, but to prevent the ball from knocking the racquet all over the place, it has to be heavy. And if the ball is pushing the racquet around, power is lost. So, the player also wants the racquet to be heavy to get the most power. But if it is too heavy, he can’t swing as fast, and he loses power. What a problem!”1

And it’s a problem with no apparent solution. You can’t have your cake and eat it too.2 One only has to look at the Big-3 to see.

At the mercy of organizers

One thing that I think gets overlooked in the GOAT debate (if we only talk about the Big-3. It’s hard to compare eras) is that the very best are (were) still at the mercy of the conditions—and by extension—tournament organisers. Let’s take the Big-3 and look at their win-rate % across surfaces categorized by speed3:

Here we see Nadal’s win % steadily improves in a very linear and predictable fashion as the court gets slower. For Federer the reverse; as the surface slows his chances of winning go down with similar predictability. For Djokovic, we see that he enjoys the medium-paced courts and suffers the most on very slow surfaces, with a slight drop on very fast courts. Of course this doesn’t factor in bounce height, balls, altitude, etc. But considering the length of their careers and sheer number of matches played I think this pattern is a fair reflection of what their games are most suited to. Take a peak at their racquet setups and you start to understand what they prioritize as well. (The following racquet descriptions are simplified for the sake of brevity. If you want to get into the weeds of racquet properties and their effects/tradeoffs, as well as various pro racquet specs, check out impactingtennis.com).

Djokovic uses a heavy racquet with a high twistweight and swingweight. He uses a large grip and tighter string pattern. At virtually every decision point it seems he has gravitated toward control rather than spin. It’s set up perfectly for someone who wants to absorb; it would feel rock-solid on impact, and that’s exactly what he excels at—especially when returning. With his more extreme grips and board-like frame, what Djokovic can struggle with at times is generating pace or being dynamic off low and slow balls, and this is exactly the kind of player he sometimes struggles with (most notably Daniil Medvedev and Roberto Bautista-Agut; players who can move well and stay consistent without giving him angle or height to work with). It’s also why his win percentage drops off on the very slow surfaces as well (a significant chunk of this is due to Nadal. Ditto for Federer). He prefers to be attacked and to redirect pace and force errors out of opponents. It’s also why I think Wawrinka got the better of him often in big matches; Djokovic struggled to dictate points from Wawrinka’s slower chip returns to the same degree Federer or Nadal could, and Djokovic just couldn’t quite hit big enough or generate enough spin and angle to get Stan out of his comfort zone.

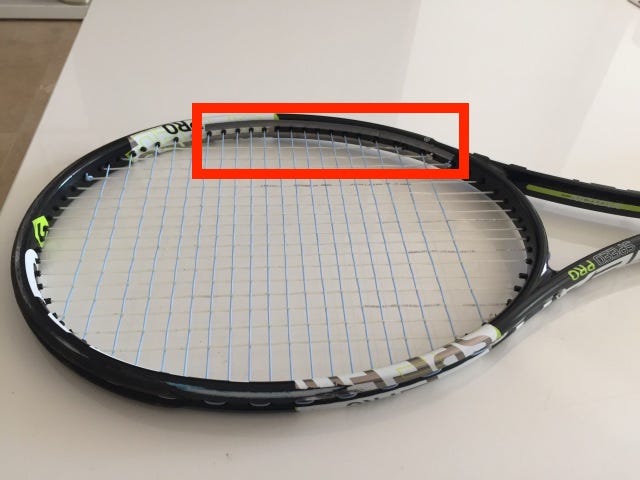

Djokovic’s racquet. Note the huge strips of lead tape on the side of the frame to increase twistweight. If he hits it off centre it would still feel plush. He also has lead hidden under the bumperguard as well. Note: this is an older frame and he has since changed specs slightly (lighter and longer frame now). Pic from TT forum poster “NikeUp”. Nadal also uses a relatively heady-heavy and high swingweight racquet, however his lead placement is far more “polarized”; the extra weight is placed at the extremes, in the handle and under the bumperguard. He also uses a much smaller grip that allows him to use his wrist more, and he uses a more open string pattern with a full bed of poly. The small grip, open string pattern, and “hammer-like” weight distribution of his racquet is set up for spin (obviously). Taking the ball flat and early is harder by design. Of course he can still do it because he’s Rafa, but he was always facing an uphill battle on a hard or grass court without much life (bounce) in it against Djokovic.

Federer’s racquet was also heavy, but his balance was more headlight, and this made the frame more maneuverable. It (partly) explains how he could hit those ridiculous flick backhands and forecourt shots off his shoelaces; with the more conservative grips he used he could employ shorter swings and stand further up the court. He used a smaller headsize for much of his career before switching to a more standard 97-inch frame around 2014. I believe there was a little lead tape under the bumper, perhaps only to help even the specs between frames. Compared to Nadal and Djokovic, I think it’s less suited for trading drawn-out baseline affairs (two-handed baseliners trend toward more even-balance frames).

How much do all these changes really matter? It’s hard to tell. My understanding is the polarized setups of Nadal and Federer may allow for a higher “peak” or “ceiling” in their level of play, but may be harder to use; they are harder to time the ball (an exaggerated example: think of swinging a hammer versus a piece of two-by-four). Again, from impactingtennis.com:

“Polarized rackets are good for spin production, but are harder to use, are less forgiving, and offer less depth control.”

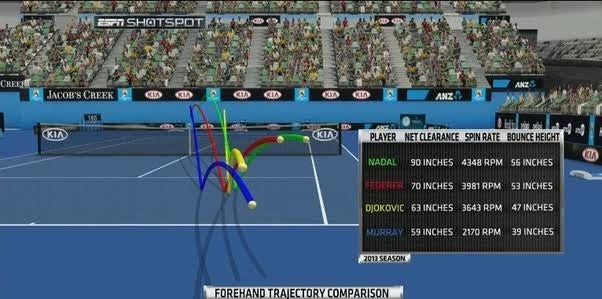

Forehand spin rates, net clearance, and bounce heights from the Big-4 ~10 years ago:

Technique dictates tactic

"Tennis played on the red clay of Roland Garros at the French Open seems to be a different sport than tennis played on the Centre Court grass at Wimbledon. The events, flow, and look of the game are completely different. And for good reason—the bounce of the ball is completely different on each surface, and it is the bounce that determines the game. That five-millisecond bounce dictates everything, including shot selection, tactics, strategy, stroke mechanics, grips, and training." Technical Tennis: Racquets, Strings, Balls, Courts, Spin, and Bounce

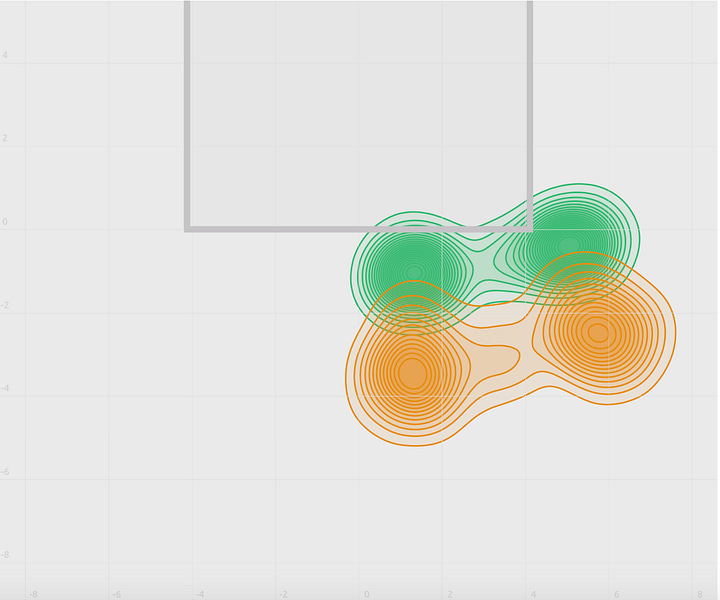

While Crawford and Cross point out that the bounce dictates the game, when we take a look at something like the Big-3 return positions (data points are from where they make contact with the ball) we can see how their swings and racquets also influence their tactics across various surfaces. These screenshots are all from a brilliant dataset from Stephanie Kovalchik’s website (www.on-the-t.com) from 2018 to 2020 ATP matches.4 Compare the first and second-serve return contact points of Federer (green) and Nadal (orange) on hard courts:

Nadal mixes his second serve positioning, but overall is always deeper than Roger. The ability to return from super deep positions is aided when you have a heavy topspin game—you can hit higher over the net and increase your margin (Ruud, Thiem, and Wawrinka all employ this. Medvedev is an outlier in that he is a flat hitter who employs this tactic). If you want an in-depth look as to why that is the case, check out

's piece here. In short, the deeper you stand the less margin you have hitting a flat shot over the net and into the court.

Now let’s compare first serve returns from the deuce court of Nadal and Federer for grass (left) and clay (right):

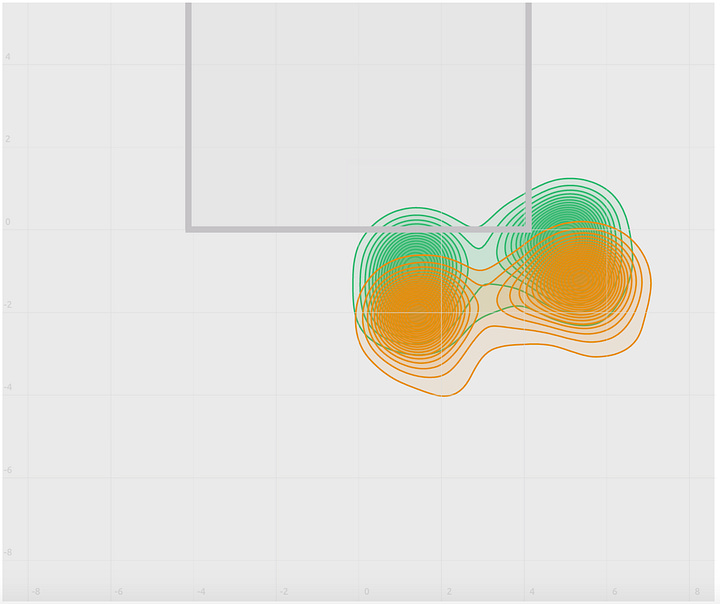

You can see that despite the differing conditions Federer barely changed position from hard, to grass, to clay to return first serves on the deuce side. His conservative grips, shorter swings, and headlight frame helped him play up and block/slice with less time (he sometimes dropped back on second serves on clay) but the pay-off of this tactic—in part—was a function of court speed. Slicing returns are safer and more effective on slick grass and hard courts compared to clay, and more aggressive rips are rewarded more on faster surfaces as well. In contrast, Nadal has shifted several metres back on clay. The extra time afforded him by dropping back helped him with his longer swings, and made timing the ball a little easier when hitting heavy topspin. He’s forced to stand further up the court on grass, and this rushes him a little and makes timing a fraction harder. Where’s Djokovic in comparison? He’s slightly deeper than Federer, but not as deep as Nadal. The same grass/clay split for Federer/Djokovic:

Djokovic’s game sacrifices spin for directional control. He can play up and more easily time the ball and get depth with his racquet setup. Despite a similar position to Federer, his tactic is distinctly different. Whereas Federer chipped and blocked serves more and then looked to attack up in the court with heavy spin and variation, Djokovic is known for his freakish ability to consistently hit deep middle returns. He’s the ultimate percentage player, applying pressure via depth and subtle change of direction, drawing errors out of opponents. Point example:

His position on the court might straddle Federer and Nadal, but overall he is slightly less offensive than both in my eyes. Coupled with a great serve, it’s been nigh unstoppable for the last decade. I wonder if night finals at the Australian Open have tipped the balance in his favor; the cooler evening conditions reduce speed and bounce—the very conditions that Nadal and Federer thrive in. Recall that Djokovic excels on the medium court speeds (he’s still very good on fast courts, but it narrows the gap). If the AO is a medium/fast court, the deep, late-night matches indicative of semi-finals and finals slowly sucks the speed and bounce out of that court.5

What does it all mean?

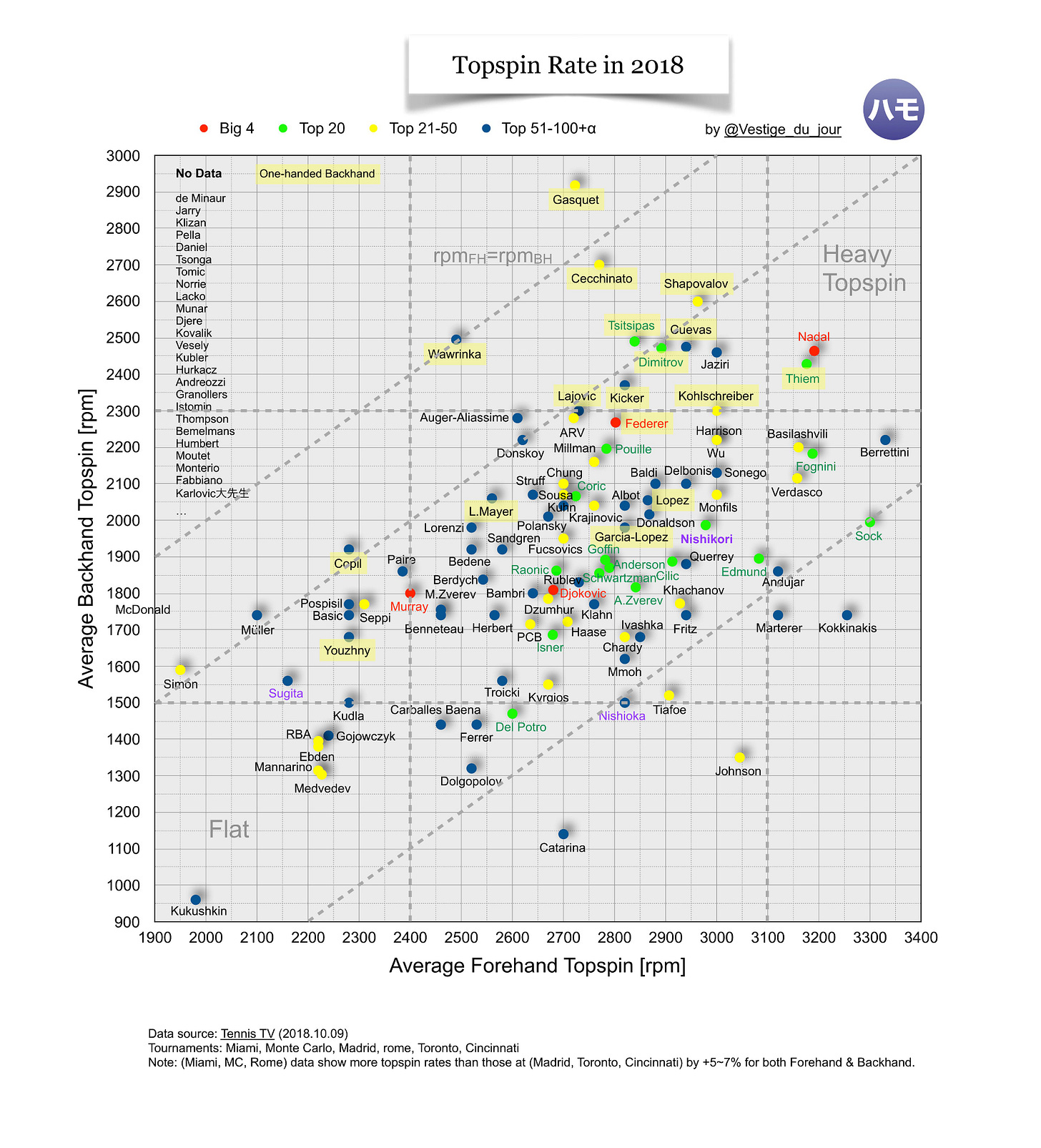

Most data that we get on TV is about ball speed and spin. More is often considered better, or at least glorified by TV commentators, and to a certain degree I think that is the case (more so on clay/slower surfaces). But while there is a strong relationship between player height and service speed, and service speed and service points won, it’s harder to quantify or draw the same conclusions for baseline rallies/groundstrokes. Movement, fitness, tactics, mentality, etc., all play a big part in winning baseline rallies. Observe the following topspin graphic from Twitter user Vestige_du_jour.

The most consistent players that come to mind—Medvedev, Murray, Djokovic, Nadal, Bautista Agut—are littered all over the map. The point is that while shot speed and spin are sometimes made known, and we get winner/unforced error counts on TV, it doesn’t really tell us how good or bad that shot is. TennisTV in partnership with Tennis Insights has started using shot “quality” as a combined measure of speed, spin, depth, width, and impact on opponent, which I think is far more informative and it is my hope something similar becomes the norm. A rock like the Medvedev backhand gets no love on speed or spin charts, but coupled with a huge serve it makes him a pain in the arse to beat. I’ve mentioned before in a prior piece:

“Many people talk of a shot having a higher “margin of safety” (height over the net) because it has more spin, but fail to recognise that it has usually come at the expense of a noisier swing; the swing has less margin for error in timing the ball. Medvedev has very little spin on his groundstrokes, but is extremely consistent because his strokes have high margins technically. These are nit-picky one-percenters, but one percent at this level is a huge difference.”

Similar to Medvedev, Djokovic also eschews speed and spin for control on the baseline.6 An excerpt from the Tel Aviv final analysis:

“While absent from this year’s US Open—won by the ultra-aggressive Carlos Alcaraz—the Serb put on a clinic in percentage tennis and showcased a style that has dominated the tour for over a decade. It is still the gold standard in my eyes. Corner defence married with controlled depth and subtle change-of-direction may not make for good highlight reels, but it allows him to effortlessly tear apart quality top-20 opposition without getting out of mid-gears.”

Frances Tiafoe’s coach, Wayne Ferreira, feels that player’s forehands today lack control despite the speed and spin they generate. An excerpt from a New York Times article:

“The reason forehands are worse today is because of the grip—you can create more pace, but you’ll have a harder time controlling it,” Ferreira said, blaming training and development that locks in these grips when players are young… “Players do very well hitting inside out forehands from the backhand corner, but because of the grip they don’t do as well hitting forehands on the run as they used to.”

While I think his Western grip thesis explains some of it, I still think the combination of lighter frames and whippy strokes is more to blame. Compare Djokovic’s forehand to Ferreira’s charge (Tiafoe) in the clips below (both players use similar grips).

Watching a United Cup match recently between Francisco Cerundolo and Borna Coric, the commentators (Robbie Koenig, John Fitzgerald, and Mark Philippoussis) mentioned at one point:

RK: “I think—just observing tennis over the last 15 years from the commentary booth—more often than not, what I see is its the lower ranked player who doesn’t maintain the level. The higher ranked player just keeps his level, rather than the higher ranked player raising his game. I think that happens a lot less often than what is spoken about. I think on the rare occasions you see two great player raising one another.”

JF: “Everyone’s best tennis is usually good enough, but it’s how long they can maintain that best tennis that has more effect”

MP: “And doing it at the right time, right?”

RK: “Especially with our scoring system”

As the 2023 season gets underway, the game is still the same one we’ve been playing for 20+ years—graphite racquets and poly strings. I still believe the best technique emphasises a reduction in lag/whip/flip on the outside. Djokovic, Nadal, Medvedev, Rune, Alcaraz,7 and Ruud put themselves in the best position to benefit as they hit technical landmarks across serve, forehand, and backhand that allow them to maintain that high level Robbie Koenig was mentioning (coupled with great movement). Of course, the game is more than just technique—talent, athleticism, mental strength, fitness, strategy, and work ethic are all instrumental—but I do think technique plays an outsized role at the very top of the game where margins are razor thin. Relying on this thesis of technical simplicity, Holger Rune is my pick of the bunch to push higher in the rankings again this year. He has such simple swing mechanics along with great athleticism, intangibles (drop shots, variation), and determination. It will be interesting to track his progress alongside others in his cohort, such as Alcaraz, Sinner, Auger-Aliassime, and Musetti.

And still there are then decisions like racquet length, balance, stiffness, grip size (Nadal’s is 4 1/4; Federer’s is 4 3/8; Djokovic’s is 4 1/2 or 4 5/8), string, string pattern, and string tension. All require a decision and all are a tradeoff.

John Yandell from tennisplayer.net (great site) often talks of the ATP “type 3” forehand that is more compact yet powerful, using a stretch-shortening of muscles. Within that type 3 I think there is still a tradeoff.

Data from Ultimate Tennis Statistics. This isn’t perfect as balls, weather, surface etc. are also factors that can affect bounce/spin/speed etc. UTS measures court speed as follows: “Court Speed - Court Speed Index (1 - 100): 80 * cube-root(Ace % * (Service Points Won % - 50%) * (Service Games Won % - 50%)) - 56, where statistics figures are adjusted with server's and returner's relative figure difference averaged by season and surface”

This dataset has hundreds of players that you can compare across surfaces, deuce and ad court, and first and second serves.

Wawrinka’s best results were on medium/medium-slow. He enjoyed playing Djokovic more when he had time and their night AO matches were some of the best baseline hitting you’ll ever see.

Of course, you need the fitness and movement to leverage consistent, slower shots as a counterpuncher; Berrettini shouldn’t change his forehand to something less powerful or spinny in exchange for control.

I love Alcaraz’s game, but feel his backhand can get him in trouble with his outside setup.

Hi Hugh, Another great post. Very interesting analysis of court speed. It seems that court speed was made more homogenous which favors Djokovic over Fed and Nadal. Fed suffered the most as higher court speed would have benefited his win record. I do have one nagging problem with deep returning. I still think that even a 30% mix of S&V nullifies this advantage. It is just too much of a liability to return from so far back. My hypothetical matchup is Sampras vs. Nadal even in today's slower conditions both at or close to their peak. I still think that Sampras wins most of the time on grass and hard courts. Nadal would HAVE to stand closer. Same with Ruud today. Just no way that standing way back will work long term. Alcaraz and Djokovic have already brought it out against Medvedev. It's a matter of time before any server immediately starts charging the net when someone stands back too far to return. They can also hit a sharp low slice serve that spins away or into the server but stays very low. Or even drop shot serve and then charge the net. In any case, I love the idea of tradeoffs!

Hugh, I love your discussions on forehand wrist position set up. I know you are a big fan of the wrist extended set up used by Fed , Nadal, Novak, Rune, etc, rather than the wrist flexion/curl/dangling set up used by Tiafoe, Khachanov, Musetti, Kyrgios, etc. It seems to me Fognini uses a completely neutral wrist set up, neither extended or flexion? What do you think? This could be an interesting compromise?