Note: I was having technical difficulties with loading videos today, so these might not work, in which case, just watch the match again. It was very good. But apologies if that is the case.

Novak Djokovic defeated Carlos Alcaraz 6/3 5/7 6/1 6/1 to reach his seventh Roland Garros final and 34th career slam final. What was billed as the match of the year certainly lived up to the hype for the first two sets, before Alcaraz cruelly succumbed to cramping early in the third. From there, Djokovic was ruthless and clinical in making sure there would be no second wind from Alcaraz.

First Set

Before the match, I tweeted a few thoughts on what Djokovic’s game plan would be:

We got a reminder of why Djokovic has amassed the most impressive resume in modern tennis in the early games. As I wrote last year after his Tel Aviv win:

While absent from this year’s US Open—won by the ultra-aggressive Carlos Alcaraz—the Serb put on a clinic in percentage tennis and showcased a style that has dominated the tour for over a decade. It is still the gold standard in my eyes. Corner defence married with controlled depth and subtle change-of-direction may not make for good highlight reels, but it allows him to effortlessly tear apart quality top-20 opposition without getting out of mid-gears.

Today certainly required top gear, and he showcased this most subtle of game styles in the early exchanges, forcing errors from Alcaraz with his ability to absorb and counter-rush the Spaniard, even off his own powerful shots:

It was interesting to see how well Djokovic not only handled the Alcaraz forehand when the Spaniard injected pace, but also how well he exposed it, especially with his backhand down the line.

What separates the Serb from the pack is not power, but directional control. Something I’ve touched on with Djokovic on the backhand, forehand, and equipment and swing trends in the most recent decade.

And that chink in Alcaraz’s armor—rushing his forehand side—has been there ever since he broke onto the scene. Following Alcaraz’s victory over Djokovic in Madrid last year, I wrote in the aftermath:

Alcaraz hit a lot of forehand winners (official stats had 35 winners and 38 unforced errors for Alcaraz’s forehand) and it was the shot that steered the fate of this match. When he is set he can unload on it with great power, and the real killer is how well he mixes in the drop shot (a new stat we will need at this rate). However, this forehand does have a chink in the armor: when he’s running to his forehand side it is far more erratic. I counted 24 misses on running forehands for just one winner (which happened at 4-4 30-30 in the third set of all the times. Talk about clutch). Although one match is too small of a dataset, I think it might be the playbook. As much as I love the Alcaraz forehand, his initial set-up with an inverted racquet head and high elbow mean he needs time to unload. It means the swing is a little ‘noisy’. It’s reminiscent of Thiem’s forehand when he first came on tour, and I think long-term drifting toward a lower elbow/modern forehand like Thiem did (and which subsequently allowed him to start winning on all surfaces against the Big-3) might make it even better.

And one year on, after his Barcelona beatdown of Tsitsipas this year, I wrote:

If there’s a silver lining for Tsitsipas it may be that getting Alcaraz running to his forehand provides him with a small crack that he can look to expose. The problem is, the tool required to open it involves a well-struck backhand down-the-line. That’s going to be hard. Maybe too hard.

Too hard for Tsitsipas. But it’s right in Novak’s wheelhouse.

Mark Woodforde: “Just an absorbing, compact return. Tsitsipas was taking big swings at those serves. Missing. Shapovalov was just way off the mark, could hardly connect sometimes.”

And it’s a shot that he showcased early on in his semi-final and final victories at the Australian Open in January.

In this newsletter’s initial essay, ‘Death of a Forehand', I asked the question if the technique of younger players—the ‘Nextgen’—had deteriorated from what was ideal with modern equipment, given there has been little technological innovation since the 1990s. Lighter racquets swung faster and kept more on the outside, or the “hitting side” seem more common and encouraged, and yet, I can’t help but think that under pressure they don’t hold up to the fuller and heavier “Ferris wheel” swings of the Big-3 et al.

While Alcaraz’s forehand is certainly more Ferris wheel than merry-go-round, I’ve often wondered if such a high elbow with an inverted racquet can be truly great on the run—light stick or not—or if he should make a Thiem-like adjustment to that side and shorten the swing overall. Today it certainly looked shakier out wide against Djokovic’s pressure, and Djokovic found it often, even when counterpunching.

As Woodforde said of the above point: “And I think the difference there again….who, this tournament, would have actually got out to that backhand and then sent it back with a little extra? That’s the greatness, the level, that Djokovic brings to this match.”

While the following quote was aimed at players before Alcaraz came along, I still think Davydenko’s general assessment is right:

“In my opinion, tennis is not making much progress. The players who are at the top now – not Nadal and Djokovic, but the younger generation –are not that good technically. I got surprised by that. It’s more physical – big serves, hitting hard–, but we still see that Nadal and Djokovic can control all this power over the new generation. They are still winning Slams and beating guys who are ten years younger than them, which is amazing. Anyway, I do not feel that the new generation is playing on an unbelievable level.”

Who is trying to emulate the Djoker’s absorbing style? Everyone seems intent on murdering the ball. I can’t remember Carlos hitting his backhand up the line with authority too often in this match. His swing is noisier and doesn’t get the outside of the ball as well as Djokovic's. A video below.

As the video states (~5:25), can Alcaraz handle that backhand technique? Absolutely, it’s a world-class backhand and he’s a phenom, “but there is a cost to everything, and the cost is going to be consistency and accuracy.” It’s not going to be as good as another phenom who swings it cleaner like Djokovic. And when put under scrutiny on the biggest stage, I’m more inclined to lean towards Djokovic’s performing better more times than not, as I wrote when discussing Rublev’s “mental” struggles:

The percentages are going to ever so slightly favour Djokovic, and it might not really pay off until the pressure rises, perhaps in a tie-breaker or fifth set, but when it does, these costs are amplified. The screams of frustration that bubble over after missing may convey a mental breakdown, but the origins of these ‘mental collapses’ are often baked into the technique.

And all of this isn’t to say that Alcaraz can’t be great with that technique. He already is great and will have a phenomenal career, but only to quell the hype around the narrative that gets trotted out so much that “he has no weaknesses”. Everyone has weaknesses. Tennis is a game of tradeoffs, and while Alcaraz’s backhand technique does lend itself to taking the ball early, I don’t think its current iteration will ever have the consistent timing of a Djokovic and Zverev backhand.

Second Set

This was one of the best sets of tennis I have seen in recent memory. Especially toward the business end when both men started to peak at the same time and we got multiple rallies of outrageous quality and variety as the young gun pushed a GOAT to his limits.

And we probably got the shot of the year:

But as Woodforde said after this shot: “You only get one point for that.”

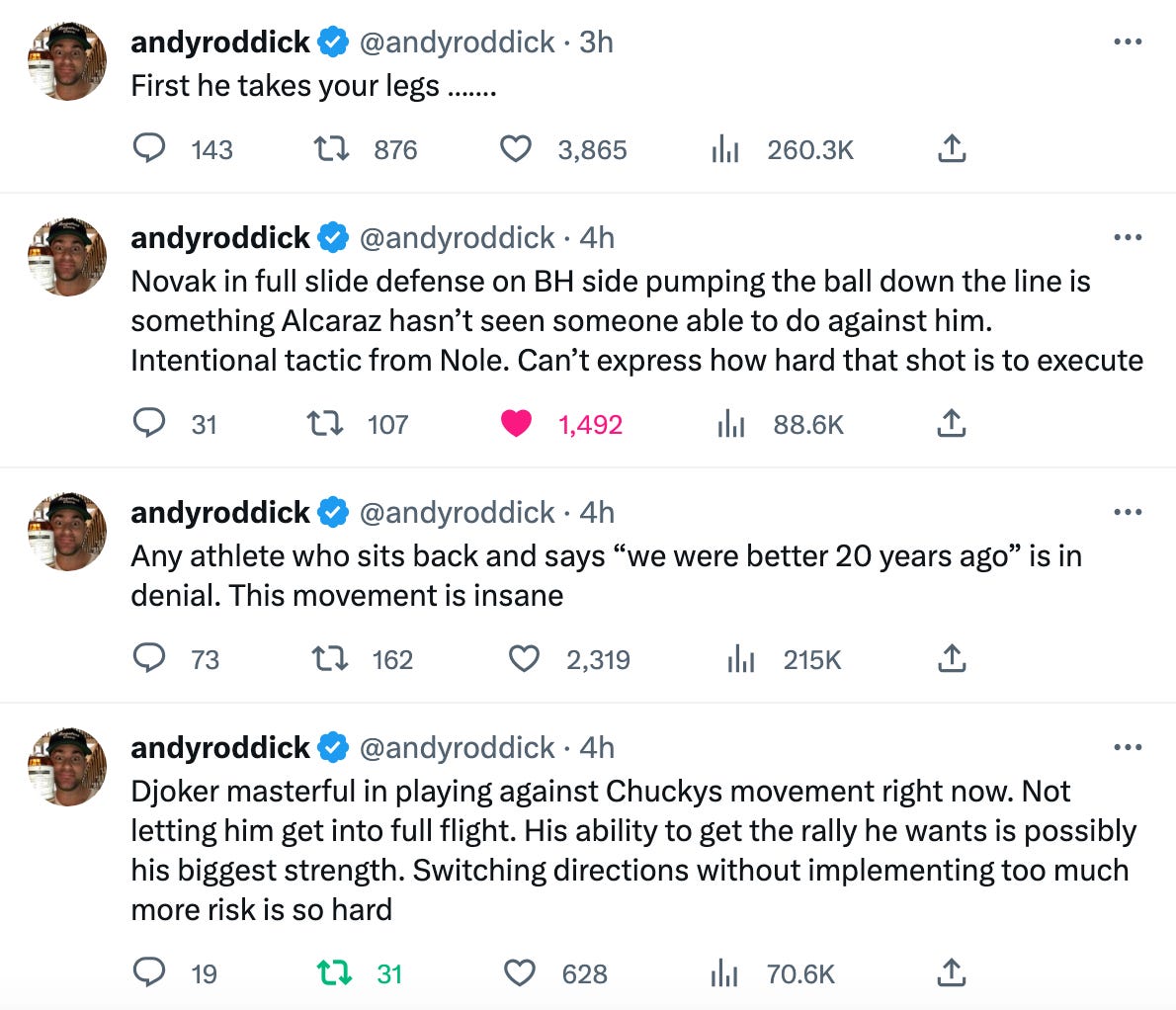

The very next point Novak went back to work, grinding out deep cross balls, extracting another forehand error from his younger, more explosive foe. All these takes from Roddick—a man who felt the full force of the Djokovic game in their later matches—are spot on:

The depth, the variety, the movement. “Tennis is the winner” of the point below, as an old coach of mine used to say:

And yet again, on the very next point, Novak grinded out another brutal rally that ended with him forcing another Alcaraz forehand error with his own deep cross-court forehand. One point is one point.

It’s funny to me that Djokovic—a guy who has a “guru holistic water healing lifeforce” vibe about him, coupled with slinky joints and swings—produces such an ice-cold, calculated style of play. It still requires a big engine to work over five sets, or at least an almost bottomless tank, and in the second set it looked like Alcaraz’s relentless aggression was starting to wear on the 36-year-old Serb. Ironically it was Djokovic who was shaking out his wrist at 3-4, looking like he was breaking down physically. The very next game, Alcaraz finally broke through with more relentless aggression (Oh look, we have sound now):

With Alcaraz serving for the set, the 15-15 point was some of the cleanest baseline hitting you will ever see. Just melting the ball like it’s Playstation:

Again, it ended with Alcaraz missing the forehand. Anyone who doesn’t think Djokovic’s forehand isn’t in the conversation of GOAT forehands just isn’t paying attention. Sure his +1 ability to be dynamic and generate isn't as good as Fed/Rafa and others, but his return, his absorption, and his redirection are second to none. It gets overlooked because winners are more memorable than an extra made ball, or a deep return that your opponent then misses. Both are worth 1 point. And so, Djokovic’s tendency to gravitate toward control over power in every facet of his game: his swings, his racquet setup, his tactics, has probably cost him some Instagram fans and highlight reels, but it’s earned him plenty of wins.

Another excerpt from a prior piece, regarding heavier racquets, with the initial quote from Duane Knudson1:

“In theory, a lower mass racket is easier to move and accuracy might improve given the more sub-maximal efforts that are used. However, a tennis player is likely to swing the lower mass racket faster; that, in general, means lower accuracy because of the well-known speed-accuracy tradeoff…A racket with greater higher mass and swingweight might help a player with long, erratic strokes and a tendency to over-hit strokes in rallies.”

If players are going to persist with these shorter/more outside setups then they must be used in service of taking the ball early and coming forward/moving up the court, which is what Alcaraz does and what an older post-2012 Federer looked like also. Staying back and trying to out-rally players with fuller takebacks turns the feature into a bug. I don’t think long-term you can win the baseline battle against the best exponents of the counterpuncher (Medvedev and Djokovic).

And once again—you can probably guess by now how Djokovic sealed his service game to get to 5-5—it was the forehand battle that the Serb won:

But I have no doubts Alcaraz is going to improve and find solutions to these chinks in his armor. It’s easy to forget that he’s only 20 and playing with more variation and courtcraft than most players could ever dream of. Not to mention that he is quite rapid:

Third Set

At this point I think the tide had swung in Alcaraz’s favour. The speed, power, and variation of the Spaniard were starting to wear down (by all outward appearances) Djokovic ever so slightly, and Alcaraz’s forehand was really humming. But in line with the theme, again:

A few points later and Alcaraz had forfeited his service game from arm, leg, and hand cramps. Replaying that second game of the third set, you can kind of see the drop in Alcaraz’s intensity after that point above. Alcaraz would win only 1 more game as he was resigned to limping around and slapping the ball.

It was a cruel finish for the tennis world, who—like me—were enthralled with the level these two brought for the first few hours. It was an incredible advertisement for the game, and one can only hope that Djokovic can bring this level for a few more years so we can see these two battle it out a few more times.

In the other semi Casper Ruud got the better of Alexander Zverev. I didn’t catch that one, but he’s certainly found form just in time and has a great forehand. It will be interesting to see how he tries to undo the Djokovic game. It’s hard not to back Djokovic in three sets; the backhand matchup is a tough one for Ruud. Nonetheless, I hope both bring their best.

Knudson, D. (2008). Biomechanical aspects of the tennis racket. In Hong, Y., & Bartlett, R. Routledge Handbook of Biomechanics and Human Movement Science.

Absolute wordsmith. Well done. I relived the match again thanks to you!

Amazingly insightful analysis, as always. You provide an extra level of understanding of this game that I find nowhere else. Keep up the good work and thank you so much!