Novak Djokovic defeated Andrey Rublev 4/6 6/1 6/4 6/3 to reach the semifinals of Wimbledon for the twelfth time. Rublev is now 0-8 in grand slam quarterfinal matches.

First Set

Djokovic, as has been the theme in so many of his recent matches (against Tommy Paul and Tsitsipas in Australia, and Alcaraz in Roland Garros), went into the dangerous forehand of Rublev in the early exchanges:

As McEnroe and Henman commented following the above point:

McEnroe: "The greats attack the opponent's strengths."

Henman: "And if you go into the strength, it opens up the backhand, which is weaker in comparison."

Rinse. Repeat.

And as is the case with Novak, it’s not the devastating speed of any shot in particular, but the compounding effect of two, three, or four balls strung together with annoying accuracy:

I’ve touched on Rublev’s backhand flaws in previous posts to highlight that his lack of grand slam semifinals has not been of mental origins, but are clearly grounded in his tennis. An excerpt:

“The screams of frustration that bubble over after missing the backhand may convey a mental breakdown, but the origins of these ‘mental collapses’ are often baked into the technique.”

Rublev sets up low and outside the ball and accelerates using a “flip”.1 This makes the backhand compact, but prone to mistiming the ball, and ultimately lacks the pace and spin that a higher and fuller takeback can get (as seen in the likes of Djokovic, Zverev, and Rune). Compounding these problems for Rublev, he doesn’t “push” the backhand with his right hand (like an Alcaraz and Agassi), but rather, tries to “roll” it with his left hand in search of topspin and control. Ironically, he would have less spin but more control if he was content to push the racquet rather than roll it.

Below we see a difference in the two outside setups of Alcaraz and Rublev.

Alcaraz has a much better power position: his racquet head is much higher, allowing him to build speed with gravity (a fairly consistent source of speed).

Alcaraz has the racquet tip finishing to the top right of the screen; he’s pushed/driven rather than rolled the shot.

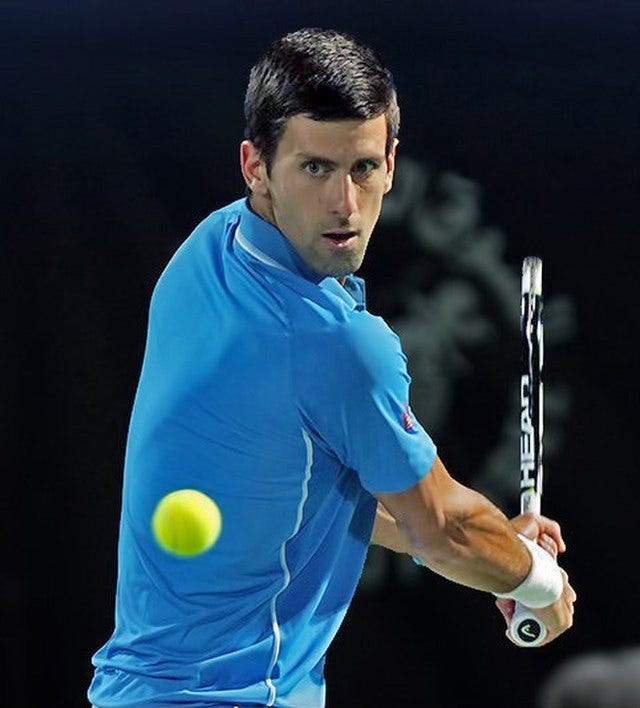

And what about that great backhand of Novak Djokovic? Well, he ticks all the boxes, unsurprisingly. He basically sets up perfectly in line when not rushed, uses a good power position, and has the head logo perfectly visible on the butt of his racquet, tracking the ball. There is nothing to undo. Just let gravity drop the frame, then push:

It’s the greatest backhand of all time.

Despite this technical mismatch, Rublev has been braver with the backhand in recent months, and he showcased his intentions to take it down the line early in the match:

Although Djokovic was looking in control and threatening in the Rublev service games, it was the Russian who drew first blood in the ninth game. Twice Rublev found width and pace into Djokovic’s forehand, the first time with a sweet inside-out backhand from the deuce return, before finding the short ball on break point with a strong forehand from wide. The ability to hurt a player from the corner was giving Djokovic a taste of his own medicine. You can see Rublev anticipate the forehand and split-step that way just before Djokovic hit it.

Second Set

The response from Djokovic was immediate. The very first point he went straight back to work, lasering the backhand line to extract another error (Now do you notice how sweet that backhand setup position is?):

Djokovic would then break the very next game off the back of some phenomenal defense:

The stretch forehand return, the sliding forehand squash fend, the trademark sliding backhand two-hander. Brilliance. And two double faults from Rublev. You just can’t do that at the start of the second set when playing a GOAT.

Double faults aside, Djokovic wasn’t just starting to turn the screws, it had been happening from the get-go:

But tennis isn’t just about winning points, but winning the important points. Rublev had that much going for him in the first set. But the backhand was starting to unravel:

And Djokovic was finding more gears. As I tweeted during Roland Garros, if you don’t think Djokovic’s forehand is in the conversation for GOAT, then you’re simply not paying attention:

Doesn’t matter if it’s Rublev, Alcaraz, or any other great forehand player, the guy can go toe-to-toe on forehands. He may not be as dynamic from the middle, creating pace and angle, but he is at his most dangerous from the corner and with pace to use. Rublev gave him plenty. The result (9.5 is ridiculous. I mean, Rublev has a sick forehand):

Third Set

Once again it was the ability to go line with control that was so difficult for Rublev to defend against. This is what a 9.5 forehand looks like. No, it’s not a blistering winner or ungodly spin, but it’s a change-of-direction ball on the run into the opponent’s backhand. That stings.

Rublev created a couple of break chances in the second game at 15-40. What does Djokovic do? He serves backhand both times (predictable to get a forehand with Rublev’s middle or off return) and then goes to the Rublev forehand on both plus-one balls. He gets two forehand errors.

And it’s this ability to hit spots—never with the most speed or spin—but with enough to build pressure that makes him so hard to beat. He takes your best shot and just makes you hit one more:

It’s the Rocky playbook, but for tennis, and right-handed, and without the stars and stripes:

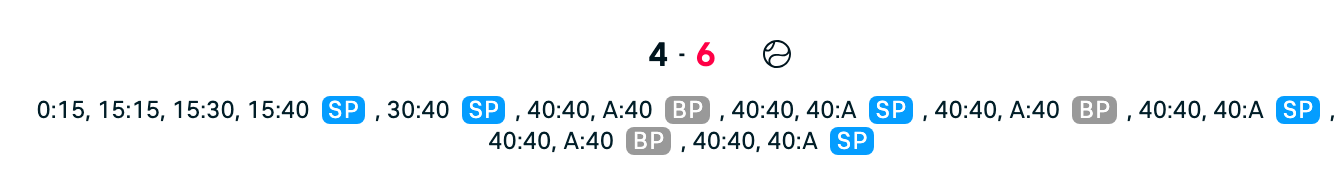

The tenth game of the set was full of drama as Djokovic attempted to serve it out. Rublev missed out on two break chances, with one of them involving a fortuitous net cord on a Djokovic second serve landing in. I mean, just the Flashscore point-by-point is pretty wild:

And although Djokovic held on there, Rublev could have taken heart that he was at least getting his teeth into some service games.

Fourth Set

It was more of the same in the fourth. If I have a criticism of Rublev, it’s his inability, or unwillingness (I’m not sure which) to add in other dimensions to his baseline game; some loopier groundstrokes, or better slices, or sneak volleys, to compliment his sheer forehand power. As it stands, he has one way of playing—tee off on forehands—and if it’s not working he looks tortured out there. The second serve continues to be a weakness as well. Great players adapt. But to be fair, the greats are also in a league of their own athletically as well; Djokovic has that ability to play subtle offence and mix in outrageous defense:

And to bring up match point:

The man is relentless.

The rap sheet

Can anyone stop him?

Next up he takes on Jannik Sinner, the young Italian who took a two-set lead against Djokovic last year in the quarterfinals of Wimbledon. I caught a bit of his match today against another power-hitting Russian, Roman Safiullin. Played under the roof, it was impressive ball striking. Just murdering the ball. However, you could level the same criticism at Jannik; there isn’t a counterpuncher’s bone in his body, and I feel long-term he needs to add in some defense and variation to become a more complex opponent. With that being said, Sinner seems to be serving a little better than this time last year, and he has been quietly solid in 2023 without a huge title. The body is always a question mark; he’s lithe and fragile, but so far everything seems okay.

I think Sinner has the game and the opportunity to really take it to Djokovic this time, and I’ll be looking forward to catching that one come Friday.

tennisplayer.net talks of the “dynamic flip” in the slot on the forehand. While it is effective for forehands, having two hands on the grip for a backhand severely limits the range of motion a player can achieve. You’re not really getting rewarded for lagging the racquet on a backhand, and it only hurts your timing.

Thanks for the analysis! Regularly look forward to these!

About Novak's forehand... as brilliant as he is overall it irks me that his forehand to my (layman) eyes seems somewhat underpowered often in random middle of the court rallies where you would think he could/should be hitting with more oomph; approach shots, and with low bouncing shots coming at him. Sometimes he hits the forehand in a way that may lack a certain pace or depth and I ask myself why he couldn't hit it with more oomph at that particular moment. In his FO matches with Nadal or his GS matches with Wawrinka he would often hit these tame balls despite having time and then immediately get blasted away.

What is the story behind that?

Various factors for those missed GS opportunities during 2012-2014 aside I think had he been more aggressive and harder hitting in some of those matches he could have 3 or 4 more GS by now.

Fascinating as always. Love reading your posts.