Wimbledon Week 1 Notes

holstered backhands — the eastern bloc — return numbers — the roast of Tsitsipas — Alcaraz is a genius and we're all idiots — Dimitrov's slice (of bad luck)

So much for that “ordered” draw I wrote about in the preview, huh? Gotta love sports.

13 men’s seeds were ousted in round 1, an open era record matched only by the 2004 Australian Open. Six more fell in round two, leaving only 13 seeded players from round three onwards.1

Here’s what I’ve been seeing and thinking about during week one of The Championships.

Fonseca Watch

Hailing from a country of 200 million people starved of a tier one prospect for more than twenty years, Fonseca was always going to be hyped on his way up. I’ve been very bullish on the teen ever since I saw the combination of forehand and backhand weaponry on display; the kid has all four shot patterns and brings the heat.

But what makes me continually double-down on the young Brazilian month-after-month are the marginal gains we keep seeing: the serve tweaks he’s made in the last year (he touched the 140s this week), the willingness and execution of his block return on forehand, as well as the slice backhand and net play.

This week, many of his backhands here at Wimbledon featured that lowered, Sinner-esque takeback that gets the racquet and hands quickly holstered at hip height. Fonseca already had that adjustment when rushed, but I felt he was doing it to a more extreme degree on the grass.

That’s kind of what Alcaraz is doing these days with his backhand: making it adaptable. And that’s a feature of great players, as I wrote after the 2023 Wimbledon final:

Sport is often compared to the brutal and competitive elements of nature and evolution, the “survival of the fittest” and all that. Turns out that is a misquote.2 It is actually better summarised as “the one that is most adaptable to change.”

And it this quality that I think defines the great players. Djokovic shared as much in his post-match press conference:

…I haven’t played a player like him [Alcaraz], ever, to be honest. Roger and Rafa have their own strengths and weaknesses…Carlos is a very complete player. Amazing adapting capabilities that I think are key for longevity and a successful career on all surfaces.”

Other elements Fonseca adapted for Wimbledon: sliding into the corners on grass

I think Matt is correct in this assessment:

I loved the body-serve serve-and-volley play against a tall guy taking big cuts with limited movement:

And while he fluffed a backhand slice on match point, overall that shot was hit pretty well for a teenaged two-hander raised on a diet of South American clay:

Why is all this important?

We’ve seen a generation of players who by-and-large stayed the same player from 20 to 27: Zverev, Medvedev, Tsitsipas, Rublev, Khachanov, Shapovalov, Fritz even, as he hasn’t developed a great net game or slice, or sliding into corners (although to his credit he is blocking returns up on the baseline this year, and that is proving very effective. More on that later).

They were unable to meaningfully add intangibles to their games (e.g., a transition game plus volley for Medvedev; slice and block return backhands for Tsitsipas; variation and net play for Rublev/Fritz; consistent execution of forecourt aggression and net play from Zverev) or address their weaknesses sufficiently (Rublev second serve; Tsitsipas’ backhand; Zverev’s forehand).

That’s hurt their ability to stay at the top and/or win big titles, because the guys beating them (Djokovic, Sinner, Alcaraz, Nadal before as well), on top of being very good athletes and elite baseliners, have all shown the ability to adapt beyond the bread-and-butter: Djokovic with his forehand aggression/serve accuracy/slice backhand/net play in his mid 30s, Sinner improved his serve/movement from the corners/forehand drop shot/willingness to move forward, Alcaraz is the poster child of adaptation, Nadal improved his slice backhand/serve tweaks/net game/not to mention multiple forehand setups.

If you can’t show signs of adaptation and experimentation, it’s difficult to keep up because the game evolves; new players will expose you in novel ways.

So far Fonseca is showing the signs of someone continually willing to adapt, and while the first-step explosiveness is the biggest hole/priority in his game, I’m betting he can improve that meaningfully too.

Fonseca leaves Wimbledon as #32 in the live race to Turin.

Digging Deeper on Return

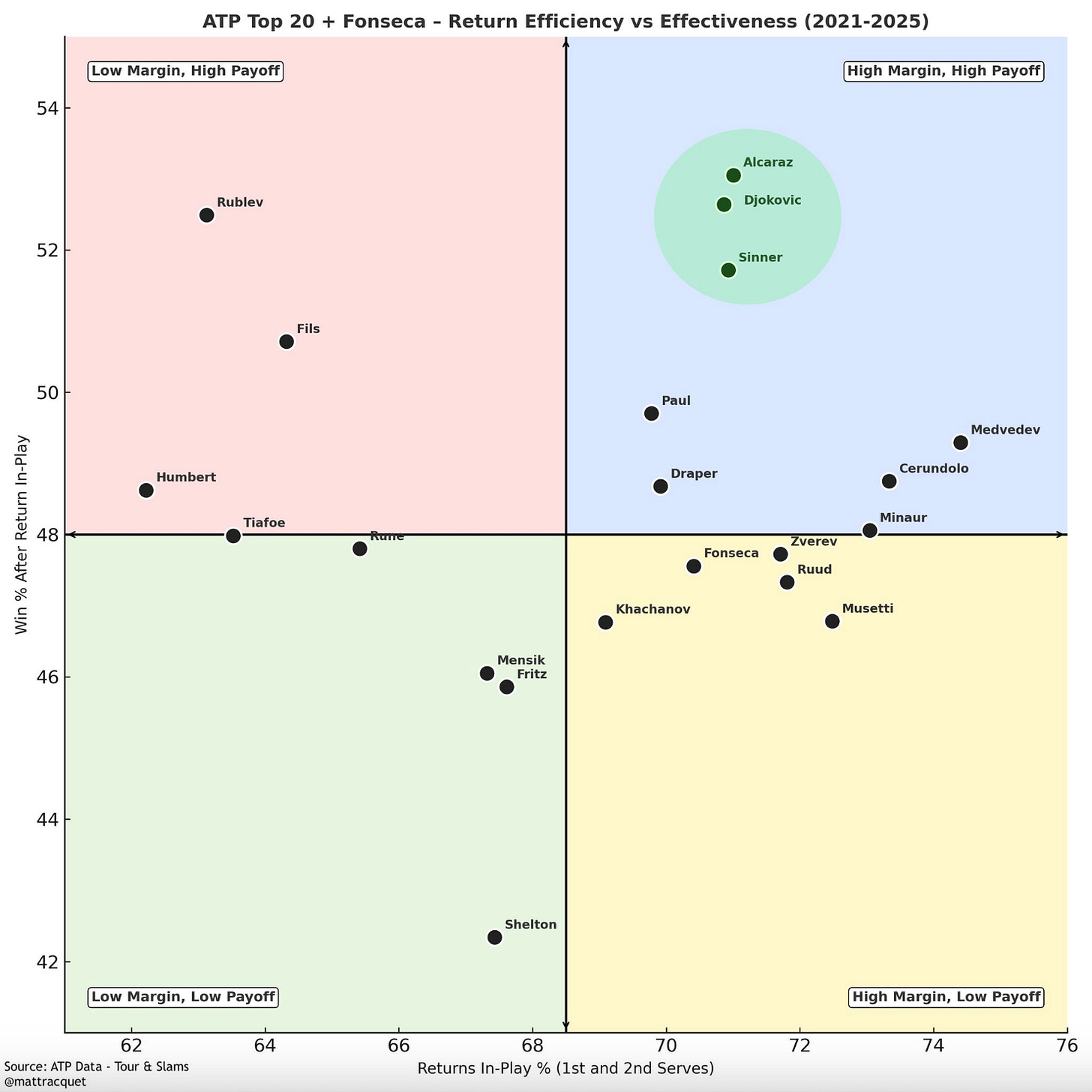

Shout out to Matt Willis again for plotting this returns-in-play % against a player’s win % after making said return. Matt also added Fonseca in here too for context.

What to make of this?

Well, you can see there is a movement divide that bleeds into playstyle: Humbert, Rublev, and Tiafoe don’t have the best end-range athletic capabilities (or swings suited for deeper positions) so they hug the baseline and play an aggressive style from the return but tend to make less returns (Tiafoe is one of the most-aced guys in the top 50), whereas Medvedev, Zverev, Ruud and Musetti tend to return from deeper positions (or block the ball when closer, in the case of Ruud and Musetti) and make more returns, and win about the same number of points once in the rally despite their deeper positions (except for Rublev, who, when making returns is elite at winning points).

Unsurprisingly, the three best players in the world are grouped closely together, tending to make a lot of returns and winning a lot of those points as well. That’s going to happen when you’re an elite ball-striker and mover.

But there’s also players grouped together for different reasons. Fritz and Mensik are hugging in the bottom left quadrant there, and I suspect both would be in the top right if they could combine Mensik’s movement with Fritz’s forehand.3

Speaking of Fritz’s forehand, Gill Gross spoke at length (watch here) about Fritz’s block forehand return that he has brought out numerous times this year.

Specifically, Fritz is using an eastern forehand grip (index knuckle on bevel 3) to block the ball back, rather than a continental grip (bevel 2) for two main reasons. The first is that this right hand grip is the same grip he takes for his two-handed backhand, meaning his right hand has no grip adjustment to make when returning his backhand or block forehand, which allows him to stand so close to the baseline and still find good contact angles against the biggest servers. The second is that using a more eastern grip to block the ball reduces the backspin and makes it a flatter strike. It’s less a chip and more just a conservative forehand block that gets back on the returner lower and faster.

On the very first point of his Wimbledon campaign, Fritz was nearly cut in half by a GMP howitzer attempting his baseline-hugging strategy:

149 mph. Travelling ~24 metres. Fritz had 0.4 seconds to react and hit the return. Blink and you’ll miss it.

Not to be perturbed, the very next deuce-side point Fritz showcased the upside, putting GMP on defence immediately off a carbon-copy body serve:

Here’s another sweetly timed winner against a net-rushing GMP, who barely has time to recover out of his serve. The ball is past him before he even gets to the service line.

Fritz came through that match in a nail-biting five sets, weathered another 6’8’’ guy in Diallo the next round in five sets, and then beat ADF and Thompson to extend his grass record to 12-1 this year.

It’s exciting to see this kind of adaptation from Fritz; a guy who loves to just play bread-and-butter power baseline tennis. I’d love to see him build off this and improve the transition game (which is looking better from what I’ve seen this week), because then you’ve got someone who could better leverage all that attacking capability.

He takes on Karen Khachanov in the quarterfinals on Tuesday.

Goran Roasts His Own Player

Goran Ivanisevic had strong words for his new charge, Stefanos Tsitsipas, following a Wimbledon retirement in round one.

“Physically he’s a disaster”

“I didn’t expect him to do well. He’s just not in form — mentally or physically. His situation is clear: if he changes certain things on the court, and above all off the court, he’ll be fine. He’s too good a player not to be in the top 10. But if he doesn’t manage to change those things, then he doesn’t have a chance.”

He also mentioned to Clay Tenis that he was hoping to make technical adjustments to Tsitsipas’ slice: a shot I’ve been highly critical of from a technical standpoint before:

“His biggest issue is his backhand, especially the slice. Technically he needs to adjust the grip a bit, and also work on his return.”

For a deep dive into Tsitsipas’s topspin backhand weakness, you can read my recent piece here:

Technical weaknesses with the Tsitsipas backhand

Note: Lots of gifs and a long piece. Best viewed with good internet and a big screen.

Another Alcaraz Record

His 12th quarterfinal already, which is, uh, pretty quick.

Carlos is doing it ‘his way’ again: five sets against Italian veteran Fognini in the opening round, three sets against Tarvet, four sets against Struff, four sets against Rublev.

But I’m not complaining. The scenic route is full of some of the most difficult shots you can pull off.

A couple of drop-volleys from No Man’s Land against Struff:

Then there was the forecourt juxtaposition of Alcaraz and Rublev. The two possess some of the biggest forehands in the game, but there transition and net games are world’s apart.

Rublev, who’s matchstick frame and intensity serves him well from the baseline, seems to snap like aspen when presented with a ball that hasn’t yet bounced.

While down the other end, Carlos has a seemingly innate measure of ball, court, and net, housed in that gifted cerebellum.

Such a match-up had me thinking of this scene from Good Will Hunting.

Alcaraz takes on Cam Norrie on Monday in the quarterfinals.

Dimitrov’s slice of bad luck continues

Dimitrov was up two-sets-to-love on number one seed Jannik Sinner before he sustained a pec injury following a first-serve and was forced to retire.

That’s now five majors in a row Dimitrov has retired from (and all mid-match, I believe).

The match itself was interesting because complementing his huge serving and forehand was heavy use of the backhand slice. In the 2024 Miami final between Dimitrov and Sinner, I felt the Bulgarian could have sliced more in that straight sets loss. On the slick grass where the ball stays low, it completely neutered Sinner’s ability to get set and dictate with authority, instead having to waste racquet head speed dedicated to lift, and producing heavily-spun, slower balls, that often allowed Dimitrov to find a forehand:

I thought it was a brilliant rhythm disrupter, able to off-set the speed and power of the serve and forehand, as well as an effective way to keep a lid on his backhand error count.

Dimitrov registered the “heaviest” (if we can call a slice that) backhand slice on tour in 2024 according to Tennis Insights; he was the king of both speed and spin:

And today he was cooking it:

While many swoon over the arabesque finish of Dimitrov’s topspin one-hander, the reality is that against the very best it’s a liability with lipstick. To reheat a Sampras quote he once levelled at Roddick:

“You were just good enough from the

baselinetopspin backhand for it to be a problem for you.”

Wishing Grigor a speedy recovery, and hope to see him playing and slicing well in the slams ASAP.

Sinner takes on Shelton on Tuesday. A look at the final eight:

I’ll be back with a semifinals preview on the weekend.

See you in the comments. HC

First round: Zverev (3), Musetti (7), Rune (8), Medvedev (9), Cerundolo (16), Humbert (18), Popyrin (20), Tsitsipas (24), Shapovalov (27), Bublik (28), Michelsen (30), Griekspoor (31), Berrettini (32).

Second round: Draper (4), Tiafoe (12), Paul (13), Macháč (21), Lehečka (23), Auger-Aliassime (25).

“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.”—Charles Darwin

Mensik and Fonseca have a smaller player sample size compared to the more established players here, given the data starts from 2021.

Sinner is a lucky boy, and it's such a shame for Dimitrov to injure himself while playing so well.

In other news, I had the chance to go to Wimbledon in Week 1. Saw a set of Fonseca, Rublev, couple sets of Alcaraz. Up close, Alcaraz's intangibles on grass are too good. he just knows when to move forward, when to hit the slice, how to turn a point around on this surface. Doesn't feel like he slows down on the grass like some others. Alcaraz's FH also has a sound off the strings that I have never heard from any other player.

Fonseca vs Brooksby was an absolute thriller. Court 12 had a queue before the match even started. The crowd love that kid, and his game is so powerful. Rublev vs Harris was the perfect encapsulation of that graph of Return made vs Return points won. I was seeing Rubles miss so many returns but whenever he made the return, he would get a good cut on it and immediately be on the front foot.

Is this the first time that Sinner faced such a lethal slice backhand? I am quite perplexed that he found it so difficult to handle this, especially since everyone knows it's a weapon for Dimitrov. Curious if Djokovic may employ it also in their semifinal.