2024 Wrap

nextgen — Fonseca — shot quality — slice

Nextgen

December means the ATP year is done…kind of. There’s been a bunch of exhibitions, but my attention turns to the Nextgen finals that begin December 18th in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. It’s hard to know if this is the end of the 2024 season or the start of the 2025 season, given a lot of players head to Australia around Christmas in preparation for the Australian Open, starting January 12 for main draw action.

I initially scoffed at the idea of a ‘nextgen’ event when it was proposed. I felt it was a desperate attempt to start filling the inevitable post Big-3 void that was nearing. Now I think of it as a net positive given that the average age of the top 100 sits ~27-28, and the fact that the tournament uses its exhibition status as a testing ground for innovation that has trickled onto the main tour. This year’s rule changes include (emphasis added):

“To enhance drama and excitement, all matches are best of five sets, first to four games, with a tie-break at three games all. Matches are fast-paced with sudden-death points at deuce. There will be no on-court warm-up and a maximum of eight seconds will be introduced between first and second serves. This also applies after a let on first or second serve. As in previous editions, time between points will be reduced from 25 to 15 seconds if the previous point includes fewer than three shots.”

I think the highlighted rule will be on the tour sooner rather than later. There’s a bunch of other innovations that you can read on the site in the linked quote above.

The eight-man field:

Unless you follow the game closely there’s probably a name or two in there you aren’t familiar with, but the pointy end of the tournament has proven a good barometer for future tour success. A look at past finalists and champions since the tournament’s inception in 2017:

So, who from this field will make the biggest splash in the coming years? I feel pretty confident that Fils and Mensik will break into the top-10 and make deep major runs at some point, and Shang and Michelsen have also shown potential over the course of the year, but despite being the last man (boy?) to qualify, I still think 18-year-old João Fonseca has the biggest upside.

I first wrote about Fonseca back in March. Of course, there’s a lot of unknowns when someone so young makes a splash — maturity, mentality, and physical peak count for a lot — but there are two observable things that make me incredibly bullish on the Brazilian: firepower, and change-of-direction.

I’ve been catching as many highlights of his Challenger matches as I can. Time and again I am seeing aspects of his game that pay big bills in men’s tennis.

The forehand in both directions is monstrous.

How does a scrawny 17-year-old absolutely melt the ball like that?

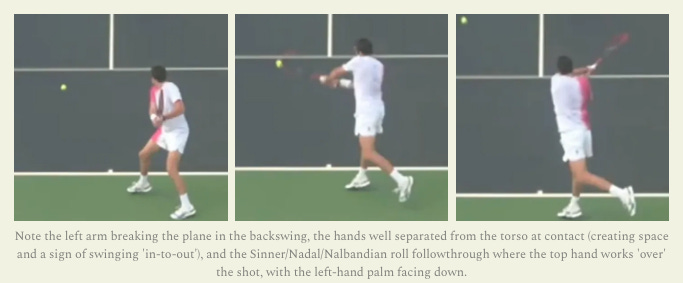

Typical of many great forehands, we see the use of gravity (by keeping the racquet head higher than the hand/elbow in the setup) to help generate racquet speed into the slot, and the kids “dynamic flip” is elite. He absolutely slingshots that thing.

But there are lots of great forehands on tour. In fact, there is an abundance of top players who are in the “great forehand, average backhand” mold — Berrettini, Ruud, Tsitsipas, Rublev, Auger-Aliassime, and Dimitrov to name a few (in one sense, great forehands often develop out of necessity when a player has an average backhand).

However, there are few players you can count who possess truly elite forehands and backhands — I’m talking power on tap and change-of-direction excellence. Who are we naming here? Sinner, Alcaraz, and Djokovic for sure, and then there’s a chasing pack of Fritz, maybe Fils, Rune at times, Draper on his way, etc.

Anyway, the Fonseca forehand got my attention, but it was the backhand that has me all-in. He’s got an unbelievable line/inside-out backhand, and that’s such a weapon to have when facing those forehand hungry players.

This year he was a winner-hitting machine according to Tennis Insights:

We can talk about statistics and performance ratings etcetera, and then you can simply observe the undeniable quality of his game:

I was critical of the Fonseca serve back in March, comparing it alongside Ben Shelton’s heavyweight load position, but since then we can see that the Brazilian has added some technical beef to the swing, creating a little more delay in the racquet position in a move eerily similar to what Alcaraz did toward the end of 2023.1

Some of his recent matches he has hit 14, 16 aces. Considering the serve is the one closed skill in tennis, and the fact he has made encouraging changes this year, I am optimistic this shot can be further developed into a reliable weapon.

Most of my long-term player predictions are more heavily weighted on efficient biomechanics. Yes the game is fundamentally a movement and balance sport, yes you need a lot of talent, yes it requires a great deal of mental fortitude, but I believe the biomechanics of swings are undersold, and when assessing young players, technical limitations are usually a much firmer ceiling than physical or tactical shortcomings.

There are fundamentals that all pros possess, but there are degrees of excellence within those fundamentals.

This is where the Berrettini backhand, or the Zverev forehand — whilst fundamentally sound — is often exposed at the highest echelons due to sub-optimal movements.

And this is why I am still bullish on Rune despite his sideways lack of progress for 12+ months. From a prior piece:

“Features that consistently appear in the best strokes can then be said to represent the “global” maximum of technique, whereas features that continually appear to be sub-optimal may only represent a "local" maximum. No matter how "talented" one is, wielding the local maximum will always have ceiling effects.”2

I believe Fonseca is giving himself the best chance to leverage his talent with his setups and swings into the ball.

Keep an eye out for him in 2025. He still has to develop quite a bit physically, but he will take bodies next year.

Fonseca takes on Fils in the night match tomorrow in Jeddah.

Shot quality

Tennis Insights released their yearly rankings for forehands, backhands, serves, etc. (I wrote about last year’s rankings here).

Here’s a comparison of 2023 versus 2024 forehands:

Zverev’s score surprised me. I thought he hit that shot as well as I have ever seen him in 2024, and Tennis Insights did note he had added speeds to his forehands in both directions this year compared to 2023, but in my eyes there are other forehands I would take that aren’t even on this list: Berrettini, Fils, Cerundolo, Kokkinakis. I guess this is where movement, confidence, tactics, and physicality play into this, plus maybe he gets opportune instances after his first-serve to attack efficiently which the algorithm may reward.

It would be interesting to see these shot metrics for pressure points only. That is, all break points, 30-30, deuce points, Ad-40 and 40-Ad, all tie-break points, and 0-30 on serve. From the Djokovic vs Tsitsipas 2022 Australian Open final piece:

A brilliant piece from Matt Willis provides the average breakdown of tour rally length as follows1:

0-4 shots: 65% of points

5-8 shots: 27% of points

9+ shots: 8% of points

However, Matt goes on to mention (emphasis mine):

“But something really interesting happens if we isolate the pressure points i.e all breakpoints (both the BP creator & defender), 30-All, deuce points, AD-40 or 40-AD, all tiebreak points, and 0-30 on serve:”

0-4 shots: 57% of points (-8%)

5-8 shots: 33% of points (+6%)

9+ shots: 10% of points (+2%)

Points tend to get a little longer under pressure. Maybe returners try harder, or servers get tighter. Either way, assessing shot quality in these pivotal moments would be an interesting exercise in understanding what a player’s strengths are.3

This one caught my attention: rally backhand slice speed x spin charts.

The red box I highlighted near the middle is Stefanos Tsitsipas. When comparing the Greek’s setup position to the slice masters of Evans and Dimitrov, we see a very distinct difference:

Much like other vulnerable swings, the root cause is often due to not swinging in-to-out enough and/or generating enough racquet speed. Here you can see Tsitsipas setup with a neutral wrist and an upright racquet head, with his right elbow lower. The Wilson stencil is above his head, rather than sitting over his left shoulder. This creates two problems.

Firstly, there’s now not enough space to generate racquet head speed — crucial if you are on the run and having to play slice defense — so the best way to hit a slice from this abbreviated setup is to hit it flatter like a Wawrinka (this is perhaps why Stef doesn’t extend the wrist, as he is pushing it more). The lifting of the right elbow helps you extend the shoulder in the down swing, and extend the elbow, helping to create that in-to-out racquet speed.

Along with Dimitrov and Evans, who else has an absolute gem of a defensive slice?

This guy.

Pick any Alcaraz match and you’ll probably find him perform this two-shot pass at least once, where the slice gets below the net of the approaching player, forcing them to hit a volley up to the recovering Alcaraz, who is so fast to make the second shot an easier winner:

I bet that shot did a lot of heavy lifting for Alcaraz’s steal score.

But the swing length is only half of Stefanos’ problem. The fact he sets up with a neutral wrist means he must make contact farther in front of his body compared to a more extended wrist. The beauty of the defensive slice, if played correctly, is that you can play it late — behind you, even — and still carve the outside of the ball crosscourt, as Alcaraz so often does.

You can see that the wrist is fixed in extension for this swing, with the wrist action confined to radial and ulnar deviation (fancy words for the wrist moving left to right, or, from the thumb side towards the pinky).

This has been a glaring weakness in the Tsitsipas game — which is a hell of a heavyweight game in other areas like the serve, forehand, and aggressive movement — since he first rose the ranks. Serving big to the Tsitsipas backhand is a lock play as he isn’t adept at blocking it like a Dimitrov or Federer. Their wrist extension bought them the precious time and space to return fast serves back from late contact points.

Compared to technical changes in other swings, this appears to be low-hanging fruit in my eyes. How one of the myriad of coaches he has cycled through hasn’t suggested this seems improbable.

Here’s a gallery of some other great slicers:

You either adapt or you don’t.

“…if there are limits in those two things [balance and biomechanics] they are going reach a certain level and they’re just going to plateau. It’s not going to be possible to take them any further.”

— Lars Christensen, coach of Holger Rune, I think…

obligatory ancient greek version:

“We don't rise to the level of our expectations; we fall to the level of our training.”

— Archilocus

The Nextgen finals start on Wednesday, with Fonseca meeting Fils in the night match in what is the most interesting matchup of the whole field in my opinion (Fonseca beat Fils — who was admittedly below his current level — during the Golden Swing this year).

I’ve got a bunch of drafts that I’m working through — a volley piece, forehand part IV, 2025 predictions — that I hope to get out in the next weeks as my coaching commitments wind down.

See you in the comments. HC

Lohse, K., Miller, M., Bacelar, M., & Krigolson, O. (2019). Errors, rewards, and reinforcement in motor skill learning. In Skill Acquisition in Sport (pp. 39-60). Routledge.

I wonder how the 2024 data would stack up given the prevailing narrative that the game keeps speeding up.

"coach of Holger Rune, I think…" LOL

Good God, I didn't know how dead the crowd was in Jeddah. I didn't watch last year. When it was in Italy, the crowd was alive and loud.