Alcaraz vs Djokovic: Wimbledon Final Recap

forehand evolution — volleys — chipped returns — adaptations

Carlos Alcaraz defended his Wimbledon title in supreme fashion on Sunday, defeating Novak Djokovic 6/2 6/2 7/6 to become the youngest player ever to complete the Channel Slam. A rematch of last year’s epic bout, Alcaraz was at his mesmerising best, combining blistering power with deft touches, as Djokovic buckled under the onslaught of the Spaniard’s dynamic game.

Pre-Match Thoughts

Djokovic’s career is a tale of two players. Djokovic 1.0 amassed his first dozen slams (2008-2016) playing as a brick wall on skates, outlasting opponents with precision groundstrokes and blanketing defence. But as the body started to spall the Serb whittled away at his serve, volleys, and forehand until they became tip-of-the-spear weapons — Djokovic 2.0 — that have bagged a second dozen since 2018. Turin 2023 was the culmination of this shift in play style, delivering straight-sets offensive beatdowns to Sinner and Alcaraz that had everyone thinking 2024 was going to be business-as-usual. While that didn’t eventuate — viruses, metal water bottles, and knee injuries played their part — I still believed Djokovic had the game and motivation to win on Sunday. Question marks surrounding the knee, as well as his lack of grass preparation, had been answered with growing confidence. His fourth-round clash with Holger Rune was classic Novak 2.0: lethal serving precision, clinical net play, and that crowd-sparked agita that is so often the source of his motivation. There has never been a greater heel in tennis.

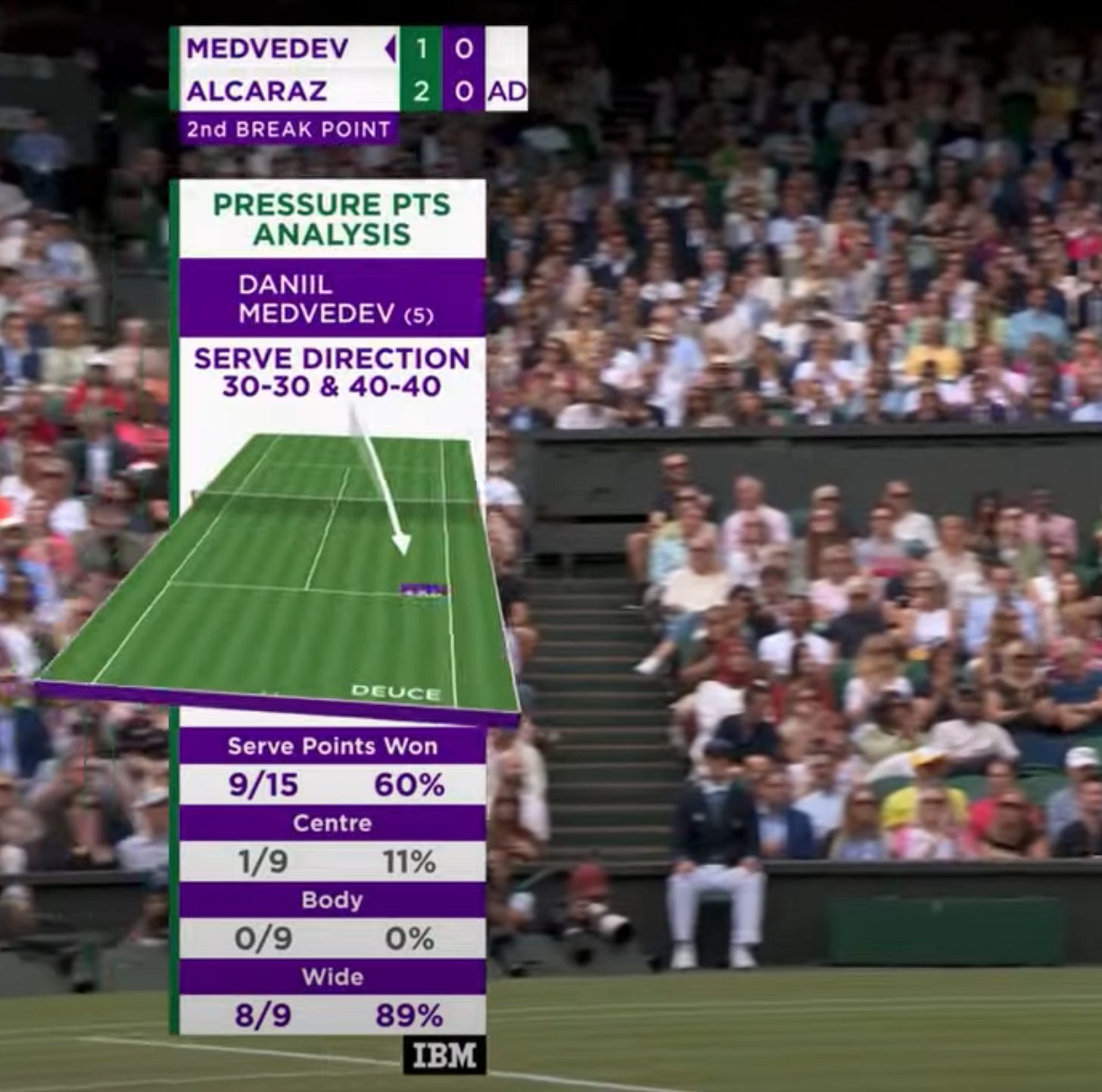

For Alcaraz, his path was less straight forward. He was nearly sent packing in the third-round against Frances Tiafoe, the Spaniard finding some clutch serving late in the fourth at 0-30. The performances were inconsistent, and the aggression of Tiafoe was a reminder that Alcaraz is vulnerable to such attacking tennis. Down a set in the semifinal against Medvedev, the Alcaraz wide forehand — a known soft spot — was found wanting, the Russian profiting from that chink in the armour, but lacking the finishing power and net prowess to fully capitalise on the match.

While the Alcaraz forehand is a sledgehammer from the set piece, capable of exceeding 100 mph, when rushed wide it can be prone to missing.

Below you can see how much he loads his legs, body, and arm to create a powerful kinetic chain. Contrasted with the inverted forehand of John McEnroe (Wimbledon’s lefty champion forty years ago), you can see how the game has evolved from the touchy feely, to something entirely martial.

I thought that Djokovic would exact revenge this year by relentlessly attacking the Alcaraz forehand. He had the serve and forecourt game capable of doing that on grass, and he came in with a full tank of gas considering his fortuitous draw.

The Opening Minutes

Alcaraz won the toss and elected to receive. Both players were edgy in the opening exchanges, but the Spaniard was quick to display the feel and hand skills that have made him a household name at 21, seen here flicking a forehand pass with something closer to eastern.1

The first game lasted 14 minutes, going to deuce seven times, before Alcaraz broke for an early lead. Djokovic came forward often to little effect — a theme that would play out for the whole match — at times undone by Alcaraz’s brilliance, but just as often undone by his own uncharacteristic volleying errors.

However, it’s never a break until you hold, especially against Djokovic. The very first point of Alcaraz’s first service game, television viewers were treated to the low parabolic camera angle. Djokovic, on the run into both corners, laced a couple of frozen-roped groundstrokes down-the-line that are markers of his greatness:

But Alcaraz followed that up with a 136 mph serve. That’s the uhh, ‘weakness’ of the kid’s game at the moment. A point or two later came a 95 mph drive forehand winner. Djokovic and his after-work-rec-league-inspired grey knee brace looked thoroughly overpowered and outmatched.

Tellingly, there was no point in the opening set where Djokovic looked to revert to Novak 1.0 — the original, I-refuse-to-miss-and-you-will-miss Novak — as an option to gain a foothold in the match. It’s likely he knew the knee couldn’t take that on, or perhaps he was confident in his ability to find his best 2.0 tennis. Either way, the first set was over in a hurry, having started as a real tussle.

Kyrgios: “I would just urge him [Djokovic] to go back to what’s worked for the majority of his career, which is being super solid from the baseline, not forcing the issue too much.”

Henman: “Do you think Djokovic has almost shown Alcaraz too much respect with the way that he’s gone out playing in that first set?”

Kyrgios: “Exactly. I think Novak’s strength’s are incredible movement side-to-side, he doesn’t give you anything to be aggressive on, and I think that’s what he needs to go back to.”

Alcaraz broke in the opening game of the second. The Spaniard was chipping returns deep middle and forcing Djokovic to generate his own ball speed (Stan Wawrinka approves), which is a slight weakness of the Serb. I charted the return strategy from Alcaraz in the second set. Of the 17 returns the Spaniard got a racquet on, 13 were directed to his forehand. This was the strategy that Medvedev had employed in the semifinal to great effect, and the one I felt Djokovic would find success with:

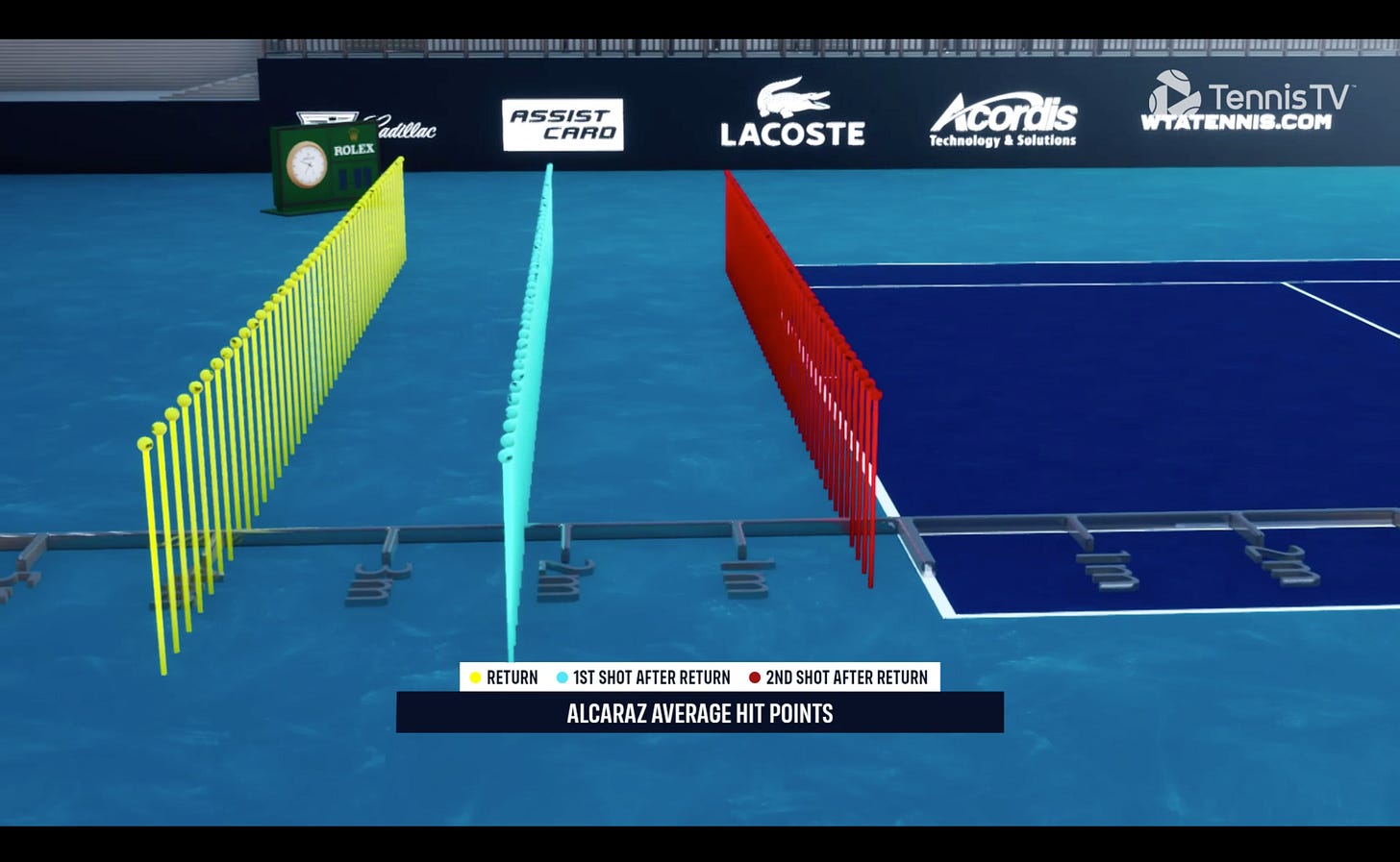

But on Sunday, Alcaraz, ever the shapeshifter, morphed into a block aficionado. Of the 13 forehand returns Alcaraz hit, 10 were blocked. He won 7/10 of these points, often baiting Djokovic into the net and then passing or forcing a volley error.

And the three topspin forehand returns? All three were missed.

Djokovic had the right strategy, but Alcaraz had adapted.

It should be said that Djokovic’s sub-par net performance, where he only won 27/53, made these chipped return stats look better, but of course Alcaraz was a factor in this.

Readers will remember from this year’s Indian Wells Final Recap the finessed slice backhand that Alcaraz is able to employ on defence. An excerpt:

There’s a lot of subtle reasons this low crosscourt slice is a boon to players who can play it. Firstly, there’s more reach when you take your left hand off the racquet, but you can also hit it slower than a two hander, so it buys Carlos more time to hit the ball and more time to recover…plus the beauty of that slice is that you can feather it to land short — shorter than you could a stretched double-hander — forcing the opponent to hit up.

This wasn’t the best execution of the defensive slice, but it still bought Alcaraz enough time to start pushing back to centre well before Djokovic could meet the ball, which was dropping to around net height when he finally did make contact. The speed threat of Alcaraz probably factored into Novak missing his volley; the court must look awfully small over there. Carlos did this three or four times on Sunday.

Irrespective of Djokovic’s lapses, the match was yet another data point to suggest that Carlos Alcaraz is built different. In big moments he finds his best tennis. Perhaps more remarkably, his best tennis is often tailored to the problem at hand. On Sunday, the return quality was largely manufactured by his power-soaking blocked returns.

Lucky for us, the Spaniard’s best tennis is also of a standard that is wholly alien to all but the Big-3. Yet for variety and shapeshifting potential, I think he is unmatched.

I must admit that I often find myself muttering quiet “fuck off”s in disbelief halfway through Alcaraz points as he traces his Aero 98 through perfect vectors that conjure ball trajectories and spins that leave me utterly convinced he is both preternaturally gifted and immune to nerves, or at least able to channel them into a higher focus. For an illustration of this I must go back to his semifinal match against Medvedev, where, stretched wide to the forehand on the net, Alcaraz sand-wedged a drop-volley at end-range using the wrong side of a western (ish) forehand grip with flawless execution.

Examples of such finesse are littered throughout Alcaraz matches. And it is the juxtaposition of these delicate operations — often threaded together as consecutive shots, or on consecutive points — with his cannon groundstrokes that make for an arresting tapestry of highlights. As I wrote last week:

“It is the synthesis of power and finesse that is intuitively attractive.”

The clay courter from Murcia can feather this:

Then two points later hit this:

And the very next point step inside the baseline and hit this:

As I wrote after the Roland Garros Final:

I don’t think anyone has ever been so comfortable playing tennis on such a wide swath of real estate. He is Nadal, Agassi, and McEnroe transfigured. And he’s only 21.

It is these chaotic, relentless, and all-court-encompassing passages of play that define Alcaraz’s style, or lack of a clear style; this kid is water, and it’s something he’s had from day one. Some of the first pieces I ever wrote on him came with a graphic that surely could only ever apply to him:

But the downside of having all these options always tends to be a lack of clarity on how you should play. Alcaraz was guilty of that against Zverev in Australia. That he seems to find the balance more often than not in big matches is testament to his game IQ.

In the third set Djokovic raised his level, finding an intensity and consistency that helped him keep parity on the scoreboard. But Alcaraz’s knifed return was still causing headaches, his athleticism from the corners handling the improved quality of the Serb’s approaches:

Meanwhile, off the ground Alcaraz was doing Djokovic things to Djokovic:2

Then at 4-4 in the third, Alcaraz absolutely melted a forehand down the line to open his return game account.

106 mph.

It wasn’t even the most impressive point of the game. This was:

Alcaraz broke to serve for the Championships. He went up 40-0 on grass. It had been an absolute masterclass from him, and a forgettable day for Djokovic, who now finds himself halfway through the year without a top-10 win.

But the Djoker wasn’t done just yet. In typical fashion when returning at 40-30, having saved two match points, Novak somehow gets a racquet on Alcaraz’s 132 mph wide serve, which of course he managed to float back to the baseline with perfect depth. This is another detail of the Serb’s game that doesn’t get crowd love, but he is unmatched in his ability to make deep returns off of big serves in big moments. Carlos opted to take a huge cut at a swing volley, missing wide as a patron screamed out before he contacted the ball. Two points later and Djokovic had broken back.

The collective conscious of Centre Court was 15,000 spectators thinking: “2019” (probably).

Both Djokovic and Alcaraz held quickly to advance to a tie-breaker. The 3-3 point was another example of Alcaraz’s ability to find deft touch under extreme duress. Djokovic wins that point — and probably the tie-breaker — against the 99, but today Alcaraz was the 1.

Again I tracked the blocked return strategy. Of 39 returns that Alcaraz got a racquet on, 19 were blocked. He made 16 of these, winning 8. Specific to the forehand, Alcaraz made 12/13 blocked forehand returns. Although he won only 4 of these points, signalling the Serb’s improved execution in the third, it was the constant pressure applied by making so many forehand returns, forcing Djokovic to repeatedly hit that extra shot, and that pressure often bled over into subsequent points, serves, and moments.

This marks the second year in a row where Alcaraz has covered his weaker points — the serve and running forehand — in a Wimbledon final. As usual, Djokovic was gracious in defeat; a quality of his that has been present from the beginning:

Djokovic: “Credit to Carlos for playing some complete tennis — back of the court, serve — I mean, he had it all today…He was an absolutely deserved winner today so congratulations to him.”

Alcaraz: "In an interview when I was 11 or 12 years old I said my dream was to win Wimbledon, so I am replaying my dream. I want to keep going but it is a great feeling to play in this beautiful court and to lift this amazing trophy.”

I’ll be back with some Olympic coverage in a couple of weeks. HC

A handy graph of forehand tennis grips from tennisnerd

From the Djokovic Movement Piece:

In more recent slam performances I’ve highlighted how he’s exposed many youngsters early in matches with his off-backhand (vs Alcaraz in Paris, and Tommy Paul and Stefanos Tsitsipas in Australia) against forehand-hungry players.

Bravo!

Loved reading about the chip/block return defensive shot. Too often the commentary was reacting to the missed volleys by Novak as a big miss. All of those volleys were below the net and that's a brutal shot to make 1. on the run and 2. trying to avoid hitting it up.

And while Kyrgios talked about Novak going back to baseline defense strategy, Novak made that choice to move forward for an obvious reason.

Hi Hugh, Yes! Old school tennis lives on on grass. We even have a 180 cm champion who is as close to the 70’s height as we have seen for a while. He is gifted but do were many players closer in height to Carlos. What is old is new!