Carlos Alcaraz defeated Novak Djokovic in the Madrid semifinals 6/7 7/5 7/6 in a three-and-a-half-hour epic. I’ll spare everyone the superlatives and dive straight into the analysis here.

Before the match, I thought Djokovic would try to keep rallies deep through the backhand channel and use his steadier shot to build pressure on Alcaraz’s flatter backhand. As it turned out, the Alcaraz backhand was rock solid, and Djokovic’s strategy seemed to be: attack the forehand. The first point of the match was indicative of the intent if only lacking conviction: Djokovic served wide, and then with the floated return went back to the forehand of Alcaraz to get him moving to that side.

Although Alcaraz belted that forehand for a forced error, Djokovic was playing to a plan and kept at it. The top players pay for deep analysis of their opponents, using companies like Golden Set Analytics to gain a strategic edge in what is a game of fine margins (Alcaraz won 134 points to Djokovic’s 131). What is clear in the aftermath of this match is that the tactic Djokovic employed was reaping rewards. I replayed the match and made a crude count of Alcaraz’s winners and errors off both baseline wings, based on whether he was set in position, or moving to that side.1 Here’s what I got for the Alcaraz backhand:

The Alcaraz backhand was an absolute rock today. He took Djokovic’s best punches all afternoon, and what this number doesn’t include is the number of forced errors his backhand yielded—where Djokovic got a racquet on the ball but missed the shot—which surely sits in the healthy double digits. I was really impressed with Alcaraz’s ability to take it hard cross, and even stepped in on some second serves and took it very aggressively. But now let's look at Alcaraz’s forehand numbers:

Alcaraz hit a lot of forehand winners (official stats had 35 winners and 38 unforced errors for Alcaraz’s forehand) and it was the shot that steered the fate of this match. When he is set he can unload on it with great power, and the real killer is how well he mixes in the drop shot (a new stat we will need at this rate). However, this forehand does have a chink in the armor: when he’s running to his forehand side it is far more erratic. I counted 24 misses on running forehands for just one winner (which happened at 4-4 30-30 in the third set of all the times. Talk about clutch). Although one match is too small of a dataset, I think it might be the playbook. As much as I love the Alcaraz forehand, his initial set-up with an inverted racquet head and high elbow mean he needs time to unload. It means the swing is a little ‘noisy’. It’s reminiscent of Thiem’s forehand when he first came on tour, and I think long-term drifting toward a lower elbow/modern forehand like Thiem did (and which subsequently allowed him to start winning on all surfaces against the Big-3) might make it even better. See Death of a Forehand Part I for more on this as well as the video below.

Nitpicking technique aside, this was a masterclass in strategy from Alcaraz as well. I don’t think tennis has ever had a teenager so comfortable on every square foot of real estate out there. For starters, he often takes on a Nadal/Medvedev style deep return position, but immediately looks to assert himself in the rally by getting up on the baseline and attacking. Just prior to the Miami event, I wrote a piece on Alcaraz:

When watching Alcaraz play you get a sense his game resembles certain aspects of Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic; that he occupies some middle ground of a Venn diagram of the Big-3. For starters, Alcaraz sees his style in the mold of Federer: "I think my playing style is reminiscent of Roger Federer's... I love to be aggressive and I like to come to the net to close the point."

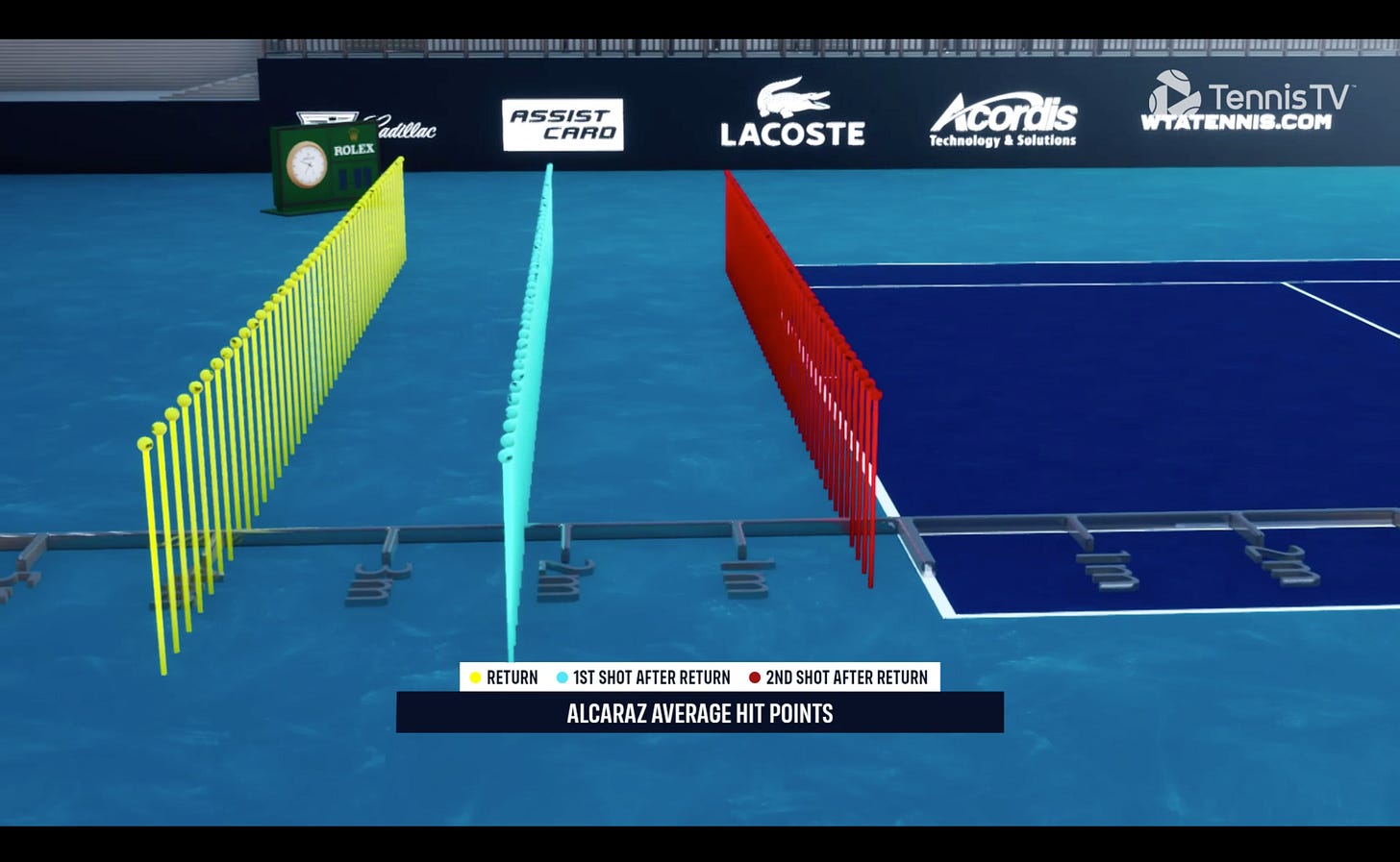

Alcaraz loves to attack, but you can see that he marry’s that aggressive instinct with a determination to get started in a lot of points by returning from very deep in the court. The below graphic was from the Miami Masters back in March (which Alcaraz won).

At their best Nadal and Djokovic were stronger from the baseline corners than Alcaraz currently is, but Alcaraz excels more in the transition game. Whilst Nadal has turned himself into one of the best volleyers on tour over the course of his career, Alcaraz’s net game makes him look like he grew up on grass, in Australia, in the 50s. For a 19-year-old Spaniard who grew up on clay in an era of baseline tennis, he is an extreme outlier. This is the special ingredient in his game for me. We’ve seen how well Djokovic—and to a lesser extent Medvedev—have been able to cover the baseline court laterally. Medvedev’s US Open performance last year was the epitome of the big-serving counterpuncher; a style that looked unbeatable at times.

Alcaraz has thrown a spanner in the works for this strategy because his drop shot is just so good. The fact that he is so aggressive and dangerous with his topspin forehand puts opponents in a bind; if you drop back several metres to handle the heat he’ll just drop shot you, but if you hold the baseline you’re going to get burned with his power. He executes the drop shot so well; it’s disguised, it’s well placed, and he can hit it off both wings equally well. He’s opened up a vacant dimension of the court so effectively.2 If I had to guess why I’d say being slightly shorter than the other top guys is a blessing that gives him an edge in control; he’s got shorter levers. Another great drop shot player I can think of—Hugo Gaston3—is also short so maybe there is a trend there. I’ve touched on Nadal’s tendency to choke up on his volley and slice grip at times, and it might be something other taller players look to adapt if they want to work this kind of finesse into their games.

“When tennis players say they admire another player’s great “feel” they are likely admiring his pre-impact racquet control that manifests itself in precisely adjusted ball speed and spin off the racquet.” Knudson. Biomechanical Principles of Tennis Technique. P 34.

The other aspect that impressed me a lot was Alcaraz’s serve. Not only did he bring a lot of heat (he’s nearly touching the 140s), but his adjustments in the match today highlight his strategic acumen. Djokovic dropped back on return at times in an effort to buy some time and space on Alcaraz’s kick serve—which was vicious in the Madrid altitude—and as soon as he did, Alcaraz would often serve and volley. I don’t think Novak burned him once. Novak struggled with the kick-serve return all afternoon, and with Alcaraz prepared to volley if he dropped back, it showcased another tactical way the young teen handcuffs opponents strategically.

To be clear, Novak and Rafa are not at their best—yet—and this is Madrid. There is altitude and a host of other young guns have beaten Big-3 guys here with the faster conditions. Novak had chances to win this in straight sets today, and he made uncharacteristic unforced errors in the third-set tiebreaker where he usually goes into lockdown mode. I am still backing Nadal and Djokovic as the favourites for Roland Garros, but Alcaraz is breathing down their necks. I still think he’s a little raw and can bleed errors, but you can see his game improving every week, and what has got everyone so excited (for me at least) is how he goes about the game; he plays with a lot of colour and variety. He’s composed, he fights like hell, and most importantly, he is winning. He had this to say post-match:

"As I have always said, you have to try to go for the match," he began. "In those decisive moments is when you see the good players and the top players, that is where you can tell the difference between a good player and a top player, like Djokovic, Rafa, [Roger] Federer, or all the players that are ultimately there for a long time.”

Mentally, he is phenomenal. Where so many times other young guys have wilted in the heat, Alcaraz thrives. Watching Zverev and Tsitsipas battle it out in the second semifinal now, the difference in these intangibles is stark; how will they bridge the gap in the coming years? You can’t learn that kind of finesse and variety overnight. Slice, drop shots, and serve-volley is sorely lacking from their games despite being five years older, and neither has been able to attain a degree of returning consistency like Djokovic or Nadal.

For Nadal and Djokovic, I’m sure they are quietly building a game plan to counter the Alcaraz game. The kick serve won’t be as high in Paris, and you can bet that both men will have a clear plan to get Alcaraz running to the forehand. Watching the tactics emerge in these two new rivalries will be fascinating over the course of the next year or so, and it will be interesting to see how many other players attempt to build the drop shot into their games.

I didn’t include drop shots or balls that were jammed back hard straight at Alcaraz (happened on return a few times). I was more interested in which side was bleeding on bread-and-butter rally balls. My numbers might be off a touch but the difference was so stark so I don’t think the general pattern is wrong.

The under-arm serve (made fashionable by Nick Kyrgios) is another example of a shot that has emerged to counter the super deep court positions of some players.