There’s a great documentary on Netflix, Untold: The Race of the Century, of Australia’s improbable 1983 Americas Cup victory over the United States. The US had never lost the cup in 132 years, and Australia II ended up coming back from 3-1 down (and well behind in the final race) to clinch the series in the seventh and final race over the US boat Liberty. Check out the trailer below.

The competition is the oldest ongoing international sporting event in the world and is considered the pinnacle of sport sailing. From Wikipedia:

“The history and prestige associated with the America's Cup attracts the world's top sailors, yacht designers, wealthy entrepreneurs and sponsors. It is a test of sailing skill, boat and sail design, and fundraising and management skills. Competing for the cup is expensive, with modern teams spending more than $US100 million each; the 2013 winner was estimated to have spent $US300 million on the competition.”

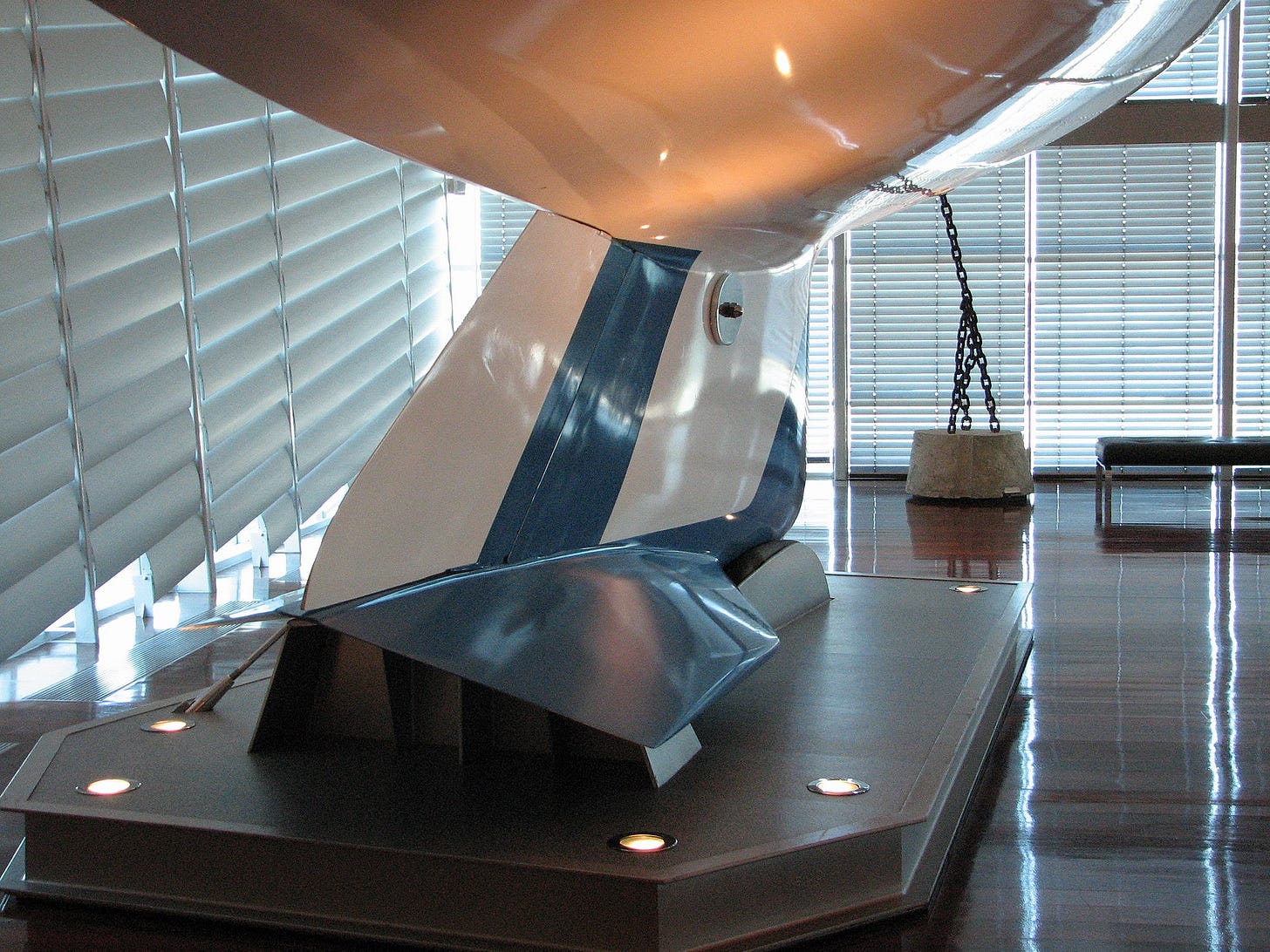

Australia II was funded by Alan Bond—an Australian businessman who was on his fourth attempt to win the cup—and designed by Ben Lexcen. Lexcen had little formal education but had been a mechanic apprentice from 14 and a boat designer from 16. Realizing the Australian boat would need to be technically superior to compete with the excellent American sailors in their home waters, Lexcen implemented numerous innovative features, such as radical vertical sails and a carbon-fibre boom, but none are more famous than his “winged keel” design that was responsible for Australia II’s speed and lowered centre of gravity.

The historic Australian win was to usher in a new era of sailing. From Wikipedia:

“Technology was now playing an increasing role in yacht design. The 1983 winner, Australia II, had sported the revolutionary winged keel, and the New Zealand boat that Conner [the US captain] had beaten in the Louis Vuitton Cup final in Fremantle (1987) was the first 12-metre class to have a hull of fiberglass, rather than aluminum or wood.”

Since Australia II’s famous 1983 win the Cup has changed hands six times in 12 series. Materials and designs have evolved year-on-year. The race is ever more about pushing the envelope on technology. Today’s yachts are unrecognizable compared to even 12 years ago, with the latest edition featuring boats with no keel and wing-like hydrofoils. As a result, modern AC75’s are exceeding 100km/h. From yachtingworld.com:

“America’s Cup class yachts, designed to sail windward/leeward courses around marks, are now hitting speeds that just over a decade ago were the preserve of specialist record attempts, while mid-race.

Perhaps even more impressive, in the right conditions when racing we have seen some boats managing 40 knots of boatspeed upwind in around 17 knots of wind. That is simply unheard of in performance terms and almost unimaginable just three or so years ago.”

Back to Tennis

Just four months before Australia II’s famous triumph, hometown hero Yannik Noah defeated Ivan Lendl in the 1983 French Open final sporting a graphite-reinforced wooden composite racquet. Noah chipped and charged successfully on red clay; a tactic that is virtually extinct even on the lawns of Wimbledon in 2022. It would be the last time a wooden racquet won a men’s singles slam. Like sailing, technology was disrupting tennis.

1983 was also the year Wilson launched its famous “Pro Staff” line of racquets. Made predominantly of graphite, these new composite racquets offered higher stiffness with less mass. Wilson is still cashing in on the frame’s legacy 40 years later with the Pro Staff v13.

“It’s a little bit vintage,” says Wilson. Spoiler: it’s pretty much all vintage. There is no new “technology”. There are only different specifications. Check out the racquet composition from 1983 (left) versus 2022 (right).

Head’s Liquidmetal and Intellifibres, Wilson’s Ncode and BLX, Prince’s Anti-Tourque System, etc. I have no idea what these “technologies” do (did), but for all their revolutionary breakthroughs it’s amazing how few tend to stick around in subsequent editions. It’s almost as if they are just trying to sell racquets.

As always, I’m interested in what really moves the needle on performance; to pinpoint the winged keels of tennis. An excerpt from Technical Tennis: Racquets, Strings, Balls, Courts, Spin, and Bounce, by Rod Cross and Crawford Lindsey (emphasis mine):

"All racquet performance technologies boil down to two things—altering the stiffness of the frame (and stringbed) and the amount and distribution of weight. That’s all. These in turn determine the power, control, and feel of a racquet. There are seemingly hundreds of technologies in the marketplace, but virtually every one of them is in some way directly or indirectly addressing weight and stiffness. But weight and stiffness can be combined in so many different ways that each racquet feels different from the next. It all depends on how much weight you put where and how stiff that material makes the frame."

Unsurprisingly, then, players rarely change their actual racquet frames over the course of a career (they do get new paint jobs every 1-2 years to market the latest racquet “technology” from their sponsors, however). What feels good is what they play with, and what they grew up playing with has by no means been made redundant in recent decades.

What emerged from this shift to graphite frames was the power baseliner. Ivan Lendl was the pioneer, running around backhands and using inside-out forehands, improving his diet and fitness, and overall imposing his game on opponents with a predominantly topspin-oriented game from the baseline that allowed him to dictate with control. An excerpt from Essential Tennis (emphasis mine):

“Lendl looked at other ways to control his success. He hired Warren Bosworth to make sure all his racquets were identically strung and weighted. Prior to that, players often went to a racquet factory and were given 40 racquets and they had to pick six or so that weighed the same, such was the lack of fine tolerance in those days. Lendl switched racquets after every ball change. One time, he pulled out a racquet from his bag, and it was still wrapped in plastic. The ESPN announcer was shocked thinking he had been sent a racquet straight from the factory. In those days, players only switched racquets if it broke or if they didn’t like the tension. Lendl decided tension loss was enough of a problem that he switched to make sure it played the same. Lendl wanted to make sure his courts at his New Haven home, maybe an hour from Flushing Meadows, were identical to the ones at the US Open, so he’d hired the guys who laid out the courts. Lendl wanted to control every variable he could.”

Jimmy Arias and Aaron Krickstein followed. Then came Agassi. These last three were all products of Nick Bollettieri1 (who recently passed away). A tough coach who was a pioneer in developing the fit baseline-crushing player that dominates both tours nowadays. The ATP wrote a tribute. An excerpt:

“With custom-fit technical and strategic advice for every player, Bollettieri and his band of loyal coaches, physical trainers and sports psychologists used video analysis to help to develop the likes of Carling Bassett, Kathleen Horvath and Jimmy Arias, Andre Agassi and Jim Courier, Monica Seles and Maria Sharapova through daily drills and competition. In 2021, Arias told ATPTour.com, “Bollettieri was about, here’s a can of balls, 30 guys who are really good, and let’s beat everyone’s brains in every day.”

Here is a young Agassi taking on Lendl in 1989. Andre’s strokes and game wouldn’t look out of place in 2022, and Lendl serves with power and dictates with the forehand. Both hit flat and struggle to defend wide balls by today’s standards.

While tennis racquet technology has been virtually stagnant for 40-odd years, the strings themselves underwent a quiet revolution in the 1990s.

Luxilon

“All stringbed and string technologies alter the force and time of impact. That is all. This is accomplished by changing the stringbed stiffness. It does not matter how you change the stringbed stiffness, only that you do. Stiffness is stiffness no matter how you get there.” From Technical Tennis: Racquets, Strings, Balls, Courts, Spin, and Bounce

Tennis changed forever at the 1997 French Open, although no one really knew it at the time. A young Brazilian by the name of Gustavo Kuerten entered the tournament ranked 66th in the world with only a challenger title (from the week prior) to his name. He would become the first player to ever win a grand slam as his first ATP title. An excerpt from Steve Tignor’s piece for tennis.com:

“But Kuerten’s Paris story wasn’t just about love; it was also about something much duller, but ultimately more significant to the history of tennis: polyester. Not clothes, but strings. While he slid and smiled his way to victory in 1997, Guga was was wielding a secret weapon inside his Head racquet: Luxilon Original string. This powerful polyester allowed him to swing for pace, and at the same time create the topspin needed to keep the ball in the court. Two decades after the oversize racquet made its debut, tennis’ equipment had, unbeknownst to nearly everyone, taken its next evolutionary step.”

Tignor kind of gets the language wrong when it comes to what properties Luxilon—and other polyester strings—provide. It isn’t power. It is the absence of power. From Technical Tennis: Racquets, Strings, Balls, Courts, Spin, and Bounce:

“The outcome of any shot depends on the racquet, the stroke, and what the player thinks the outcome is. An example is when players say that string material affects spin and that they get much more spin when they use stiff polyester string instead of a softer nylon. As we will see later in Chapter 4, lab tests have shown that string material, tension, or gauge do not have much, if any, effect on spin. When a player uses a stiffer string such as polyester, he loses power. He thus swings harder, and a faster swing creates more spin. The player then says that the string caused the additional spin, but, in fact, the player caused the spin by swinging faster to make up for the lost power. The player’s explanation of cause and effect is incorrect, even if the outcome of more spin is true.”

Kuerten would end up winning three French Opens and a Masters Cup (defeating Pete Sampras on an indoor hard court). Players complained that polyester strings should be banned. It changed the game in a big way. Agassi writes in his autobiography, Open:

“People talk about the game changing, about players growing more powerful, and rackets getting bigger, but the most dramatic change in recent years is the strings. The advent of a new elastic polyester string, which creates vicious topspin, has turned average players into greats, and greats into legends. [Coach Darren Cahill] puts the string on one of my rackets… In a practice session I don't miss a ball for two hours. Then I don't miss a ball for the rest of the tournament. I've never won the Italian Open before, but I win it now, because of Darren and his miracle string.”

Nearly three decades later tennis is still a product with Luxilon firmly at its core.

Windows of Dominance

Federer 2003 was the first time tennis saw a truly complete player. Up until that point players kind of focused on the two or three things they did well and molded their games with clearly defined tradeoffs (it still is a game of tradeoffs, but the requirements have narrowed and the gaps have shrunk. More on that later).

Andre Agassi was short and stocky. He stood close to the baseline and crushed the ball flat off both sides. He wasn’t interested in defending much, and his serve was good without being a major weapon. He didn’t hit many drop shots and he preferred to hit drive-volleys over a conventional net game.

Pete Sampras was as athletic as anyone to play the game. Greatest serve motion ever for me, an unbelievable forehand that was a trademark on the run, a slam dunk smash, great hands at net, but his backhand was weak and he couldn’t win on clay. His grips and game would look distinctly old-school in 2022.

Tall guys (Todd Martin and Mark Philippoussis at ~ 6’5’’ and change) weren’t good movers and it was accepted that this was the tradeoff for being that tall with bigger serves and power games.

Federer’s generation: Hewitt, Ferrero, Nalbandian, Davydenko, Roddick, Haas, Coria, Robredo, and Safin, did well to blend and blur the distinction of these categories. The taller ones moved better, the smaller ones were quicker with finesse—Nalbandian and Davydenko in particular were excellent technicians that made them dangerous off the ground despite their stature. They had better conditioning and swings suited for Luxilon, and they benefitted from Pete and Andre losing their physical edge in their early 30s. Pete and Andre’s window of dominance was over. Peak Federer was a product of ideal modern technique meeting Luxilon’s dampened control. Watch the point below.

While Federer usually gets lumped in as being of the same generation as Murray, Djokovic, and Nadal, to me there is a distinction between these Big-4 members and the players I mentioned in the previous paragraph. While there is no winged keel moment to separate them, we start to see a shift in their physical attributes and style; they are almost as tall as Safin, yet move as well as—if not better—than Hewitt et al. Here is Federer v Safin from the 2004 Australian Open final. Both are great technically from the back. Neither slides on defense (yet), and both try to hug the baseline and play first-strike tennis.

Just three years later we see Djokovic v Nadal in one of their early meetings as teenagers. Even if you close your eyes and just listen you can hear the difference; there’s a slower cadence to the rallies as they both stand deeper and screech rubber on defense. Open your eyes and you’ll also see that their end-range capabilities are distinctly better than Federer/Safin and on a different planet compared to Lendl/Agassi.2 Hardcourt sliding was a staple of their games, but, their technique was no different from the prior generation; heavy racquets, upright forehands, full turn backhands.

That was more than fifteen years ago.3 Both those versions of a young Nadal and Djokovic would do well today, and part of the reason they have enjoyed nearly uninterrupted success over the newcomers is because the game hasn’t really evolved from this version; there’s been no winged keel since Luxilon. The game has only changed by degrees. Their window of dominance will only close when they get old and slow, which itself has been extended with better recovery science.

Only one player was over 190cm in 2005 (Ivan Ljubicic at 193cm). In 2022 only one player was under 190cm (Rublev at 188cm).4

A collection of racquet swingweights of top players across generations. Taken from internet databases so take with a grain of salt (e.g., Alcaraz at 316 is unlikely I think, but for the most part there is a trend).5

In summary, younger guys are taller, serving bigger, moving better, and swinging lighter sticks with shorter swings. Yet, the Big-3/4 kept dominating. It’s not clear gatekeepers of today (Berrettini, Zverev, Tsitsipas, FAA, Rublev, etc.) are better than gatekeepers of the early Big-4 era (Davydenko, Berdych, Nalbandian, Ferrer, etc.). Davydenko echoed the same sentiment earlier this year:

“In my opinion, tennis is not making much progress. The players who are at the top now – not Nadal and Djokovic, but the younger generation –are not that good technically. I got surprised by that. It’s more physical – big serves, hitting hard–, but we still see that Nadal and Djokovic can control all this power over the new generation. They are still winning Slams and beating guys who are ten years younger than them, which is amazing. Anyway, I do not feel that the new generation is playing on an unbelievable level.”

Grassroots

If you’ve read this newsletter for a while you’ve probably read Death of a Forehand. In short, it asks the question if changes in grassroots tennis have led to less efficient swings and lighter racquets that don’t provide as much control as the Big-3 et al. My hunch is that technique matters a lot at the very top of the game for two reasons:

Movement and athleticism can’t be leveraged well without great technique (FAA, Rublev, and Tsitsipas are great athletes but they struggle on defense because of technical issues on their backhands).

Tennis is a game decided by a couple of very important, pressure-filled points. Under pressure you want fewer moving parts. Simplicity is less likely to crack. Furthermore, despite the insistence around the game getting faster/more aggressive etc, a tendency we see in professional tennis is for rally length to increase on pressure points. Details below.

A brilliant piece from Matt Willis'

with the average breakdown of points is as follows6:0-4 shots: 65% of points

5-8 shots: 27% of points

9+ shots: 8% of points

However, Matt goes on to mention:

“But something really interesting happens if we isolate the pressure points i.e all breakpoints (both the BP creator & defender), 30-All, deuce points, AD-40 or 40-AD, all tiebreak points, and 0-30 on serve:”

0-4 shots: 57% of points (-8%)

5-8 shots: 33% of points (+6%)

9+ shots: 10% of points (+2%)

We can see that in big moments the play gets safer. I echoed similar thoughts after Djokovic’s triumph at Wimbledon:

“One of the hardest things about playing Djokovic is the difficulty of winning important points. As the occasion grows, the style of tennis of most players converges towards the safe and consistent style that Djokovic epitomizes, and so solving the Djokovic game presents players with a puzzle; as you get closer to beating him, you instinctively tend to improve his odds of winning points, and kill your own.”

One of the hallmarks of the Big-4 over the generation they succeeded (Hewitt et al.) that I mentioned was the emergence of that ‘patient/stubborn refusal to miss’ mentality as an MO. Sure Hewitt and Coria had that, but they were under six feet with little hitting power. These four could hit/serve as big as Safin and then move as well as Coria with the same kind of shot tolerance. On big points they would be tough in the sense that they played percentages and they just did not miss. They were content to make opponents take on risk.7 In contrast, many youngsters today—Sinner and Alcaraz lead the way, but it also includes Thiem, Shapovalov, and Rublev—seem intent on playing a brand of huge power and aggression as their MO.

I’ve pointed out in many posts what I think are technical weaknesses in many of the younger players, and in summary what tends to be the rage at the moment is shortening and lowering swings/using lag, or ‘the flip’. Yes, it can work with certain strokes/set-ups, but my hunch is that we’re moving away from simple fundamentals. Rick Macci talks “new” backhands below.

Some excerpts:

“In 2020 the next generation backhand—because time is of the essence—everything goes so fast…preparation—which we thought many years ago wasn’t a big deal—it’s everything…

“Racquet to the outside—keep it to the outside—because we’re going to make the racquet flip, just like on the forehand” [fundamentally different strokes but okay Rick]…. “I’d be at around 7 o’clock. You see Kyrgios and he’s almost at 8 o’clock.”

4:45 to 5:05 is one of the craziest things I’ve ever seen. It’s information soup.

Then he mentions Djokovic as setting up on the outside. Here’s Djokovic from a few years ago setting up way inside.

In 2022, Djokovic has shortened the backhand, but it is not setting up on the outside, it’s perfectly straight to inside for line balls. If he’s very rushed he will set-up outside, but his stock backhand is not like this.

Ditto for Patrick “The Coach” Mouratoglou. He emphasizes this wristy-ness that just isn’t all that evident in great backhands. The kid below is setting up his racquet tip/angle in a different postcode from where the greats are. In fact, I would almost argue you want to just do the exact opposite of what PM says in most of this video. If he says set-up here, go there, and if he says use the wrist here, keep them still. Zig where he zags and you should turn out alright.

In my humble opinion, this emphasis on shortening/lagging/flipping the racquet has had an overall net negative effect on players. Yes, there are times when you need to shorten the swing, but should that mean it becomes your stock take-back? Is the game really that much faster than ten years ago? I don’t think it is. In so many shots with this stock outside set-up/flip it seems to be a bug, rather than a feature.

There are tradeoffs; the swing will be shorter, you may get more spin, but at what cost? In the big moments the trend seems to be about managing risk, not finding more power. In those moments you want control. Looking back since 1983 and the birth of the graphite racquet, at every step—from Lendl to Luxilon—it’s always been about finding more control.

Here are four players with fuller swings/less ‘flip’/lag/wrist emphasis who have done well recently.

Djokovic

Thiem

Medvedev

Ruud (I touched on his recent backhand change here).

Rune

Medvedev is basically antithetical to this emphasis on lag and shortened swings, yet he is one of the most consistent players on tour with very flat strokes. He’s been the one guy who has consistently pushed/beaten the top brass (along with Thiem pre-injury).8 Sure his style is often to counterpunch from a deep court position, but then look at Thiem and Rune for more traditional size/styles. Both guys can crush the ball flat and up in the court because their forehands are just shortened versions of the modern forehand (upright racquet-head with gravity).

As always there is nuance to be had when talking backhand set ups. You can set up outside/lower if you have a flat swingpath and conservative grip, and if you are rushed. Agassi shortened like this later in his career to maintain an aggressive court position, and we see it done well by guys like Mannarino, Tiafoe, Paul, Norrie, Kyrgios, etc. But, the very best backhands are setting up with full turns: Djokovic, Zverev, Medvedev, Rune, Paire, etc. YouTube ATG backhands: Nishikori, Nalbandian, Djokovic, Nadal, Murray, Zverev, Hewitt, Safin, Medvedev.

In summary:

We have had a tech stall for 30 years. Unlike sailing, we have not had a winged keel moment that should warrant a change in technique/tactics.

Modern players are overall better athletes (taller and moving better) thanks to sport science improvements in fitness and recovery. On the flip side, this has helped the Big-3 extend their dominance into their mid to late 30s.

But, I think they (youngsters) are worse technicians (lighter racquets, shorter/wristier/noisier swings) that are more likely to be inconsistent/buckle under pressure. The emphasis on shorter, wristier swings prioritizes spin and preparation over control and feel.

Big points in tennis tend to be longer; more about control. You want to be able to leverage your movement and handle pressure.

The very best youngsters (Medvedev, Thiem, Rune is coming) are still exhibiting the same technique as the old guys (i.e simpler mechanics).9 This is no surprise to me, as the game is the same thing from 15 years ago.

Jimmy Arias was really the first to use the modern forehand technique we are familiar with today, and it was developed by his electrical engineer father before Bollettieri claimed it as his own.

Matt Willis of

did a great piece on sliding/movement evolution in men's tennis that you can read here.Carlos Alcaraz would be the exception also if he hadn’t pulled out.

Same data set from Death of a Forehand. You can look up specific player values there.

Matt acknowledges the data source: “Thanks to Shane Liyanage for these and the figures below, taken from the Data Driven Sports Analytics database — sample size 2000+ matches.”

To varying degrees. Federer (especially) and Nadal were more risk-on than Djokovic and Murray for the most part.

del Potro is another example. Big guy, full take backs, flat strokes. Yet, he was clearly the next best thing in tennis. A healthy Juan would have had a phenomenal career.

Some may mention Alcaraz. While he certainly looks like he is going to be an ATG, I don’t think it will be because of his backhand set-up, rather, it will be in spite of it (and he may even change it still, as his younger days had more turn).

Wonderful analysis. I always wonder how getting a single breakpoint all match is more than enough for Djokovic to win best-of-3 matches. I think having better control than his opponents in tight matches + winning important points have been his recipe for success during the latter part of his career.