Rublev and the Mental Mirage

technical and physical limitations—tennis as poker—improving your hand

World number 8 Andrey Rublev captured the Belgrade title last week, storming home 6-0 in the third set against world number 1 Novak Djokovic in the final. Djokovic is clearly not back to being Djokovic yet, but it was still a strong week for Rublev, who now has three titles on the year.

In a recent interview with Tennis Majors, Rublev was asked what he thinks he needs to improve in order to take the next step and become a genuine Grand Slam threat (emphasis added throughout):

“…sometimes I watch videos and I think ‘what am I doing?’ I am trying to eradicate those things (hand biting and yelling) from my game. I want to be more professional and more positive on the court. I feel like that is what I am missing in order to reach the next level….The mental aspect of the game…I cannot allow myself to waste time and energy on the nonsense I sometimes do, it is better to focus on the game itself and to fight for every ball.

So often the difference ascribed to the winners—let’s say, the ‘Big-3’—and the cadre of ‘NextGen’ players (Rublev included) unable to topple them is put down to ‘the mental game’. That Roger, Rafa, and Novak somehow possess supernatural mental strength, or that the rest of the tour is lacking a strong ‘mental game’. Some blame social media’s influence on the attention spans and motivations of younger players or the negativity that floods the comments and messages of an athlete after a loss. All may play a part, but we must acknowledge that the Big-3 are better mainly because they are better at tennis; you can’t ‘mental’ your way to hitting your forehand like Rafa or sliding on your backhand like Djokovic. It’s tempting to prescribe mentality as the tonic that will take a player to the next level, especially when we see guys hold their own for a set—or even beat the Big-3 in smaller events—only to unravel when it really matters in slams. But it’s my belief that ‘nerves of steel’ must sit upon rock-solid technique and physical athleticism. I call ‘mental toughness’ a mirage because of their similarities. A definition of mirage:

an optical illusion caused by atmospheric conditions, especially the appearance of a sheet of water in a desert or on a hot road caused by the refraction of light from the sky by heated air.

Like a mirage, mental toughness is also (mainly) an illusion; from the perch of couch and commentary box the Big-3 appear supremely poised, unflappable in the moment, yet upon closer inspection, the effect is mainly physical. Nadal—a mental giant—explained as much in an interview with El Hormiguero (emphasis added):

"You often talk too much about mentality. But when you usually win, it's because of how you handle the ball, and then only because of mental aspects…But when things get complicated, success comes when you are ready to fight for it. And if you can handle the pressure. When you are able not to lose your skills in these situations."

It’s not a coincidence that the most athletically gifted and technically proficient tennis players are also considered mental giants in big moments. As I’ve written about extensively before on forehand technique (and touched on backhand technique here) great performance has a signal that we can trace back to physical and technical origins that give players a greater sense of control over the ball. It’s interesting to me that Nadal says “not lose your skills”—like it’s a game of maintaining when the pressure builds, even though most commentators and pundits talk about rising to the occasion, similar to Usain Bolt maintaining his speed longer than his rivals in the last strides of the 100m dash. For tennis, I’d argue that maintaining skill under pressure rests upon simple tactics and techniques that give a player a sense of control, something that Rafa has in spades with his lefty crosscourt forehand. If you have this, then you’re less likely to buckle in the big moments.1

Tennis as Poker

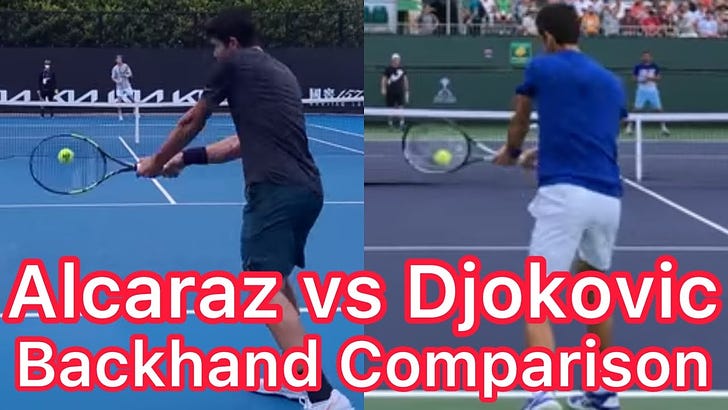

Tennis is a difficult sport to dominate because a player has the upper hand each time they get to serve; to be number 1 in the world only requires that you average ~55% of points won.2 You’ll hear commentators talk about ‘percentage plays’ often as a way of communicating that fact. Like poker, the better player doesn’t win every point, but over time the percentages start to matter; a player with the weaker hand can get lucky on the river only so many times. Djokovic going into the Rublev backhand would be a great percentage play for Djokovic because his backhand is akin to pocket aces, whereas Rublev has a little less margin and dynamism on that side, in part due to his shorter, wristier swing. For a proxy to the Rublev backhand, check out the Alcaraz v Djokovic backhand analysis below. As the video states (~5:25), can Alcaraz (and Rublev) handle that technique? Absolutely, it’s a world-class backhand, “but there is a cost to everything, and the cost is going to be consistency and accuracy.” The percentages are going to ever so slightly favour Djokovic, and it might not really pay off until the pressure rises, perhaps in a tie-breaker or fifth set, but when it does, these costs are amplified. The screams of frustration that bubble over after missing the backhand may convey a mental breakdown, but the origins of these ‘mental collapses’ are often baked into the technique.

Finding patterns of play that tip the percentages in your favour is the aim of the game; having better strokes and movement opens up more patterns that you can execute reliably, on top of simply being favoured in more of those patterns. This is why head-to-head wins can skew wildly based on surfaces and matchups3. So the ultimate aim is to improve the hand you’re currently sitting on. Part of that hand has been dealt for you—by the athletic gifts of your genes, how and where you were taught the game, and yes, I think your disposition counts some. Improving your hand is entirely based on what you do and how you do it. Improving your ‘mentality’ can assist in playing your current hand better, but it is limited by what it is working with.4 By comparison, improving your technical or physical game is like swapping a King for an Ace; it improves your chances of winning and probably gives a boost to your mentality for free—winning breeds confidence (and increases testosterone).

It’s clear Rublev has a great forehand, he can generate a heap of spin and power off that wing, but there are areas where his game is lacking. Of course, he knows this, as he said in the same interview (emphasis added throughout):

Game-wise, there are details I need to work on. I need to develop a better feel so that I can return more balls in the court, slicing for instance. Some players do not play aggressively, but they give you balls that are pretty difficult to attack – sometimes, I lack those kinds of shots in my game. Furthermore, I need to have more confidence coming forward. There are a lot of rallies where I get a shorter ball and I do not come to the net because I am uncertain. Or I do come, but you can see I do not feel that comfortable. I need to break that barrier in my head because I feel I can get more points that way. Also, I need for my second serve to be faster. It would be a huge advantage, since it would be harder to break me. In part, that is mental as well, because in practice I hit second serves harder and I rarely make double faults. But in the match, when I feel pressure, sometimes I am afraid to go for it, particularly when it is 30–30 or break point or advantage. Then I just push the ball in order to start the point. I need to say to myself ‘just do it’.”

The bolded quotes highlight the difficulty of improving at such a high level. Rublev knows he needs to come forward more often to capitalize on his powerful groundstrokes, yet he isn’t that comfortable at the net because he’s never had to come forward, as his groundstrokes win him most of the points against most of the field. It’s not an easy problem to solve. It’s hard—really hard—to get comfortable slicing (especially as a two-hander) or to become solid on the net. I’m surprised other players that aren’t natural volleyers haven’t imitated Nadal’s choked-up grip to gain a little maneuverability and control—he’s become one of the best volleyers on tour (he often slices with the same choked-up grip as well). Maybe a cue or a metaphor can help a player take that step on a stroke. Maybe fatherhood or a long injury lay-off provides some calming perspective in big moments. Other times a minor tweak to the grip is the difference that gives them the confidence to move forward. There is no magic potion. Each player has to test and tinker with everything in training.

In Rublev’s case, I’m not sure mentality is where he is really lacking. Let’s keep in mind he’s top-10 in the world. Sometimes taking the next step isn’t possible because your peers just take bigger steps (ask Andy Roddick). He works hard and has won plenty of titles. The players ahead of him are simply a little better at tennis—for now. Would I change Rublev’s backhand to something like Djokovic’s? Absolutely not. I think it would be way too difficult to make even that minor technical change, and it would most likely just lead to him over-thinking that shot when it’s pretty darn good. But would I look for Nadal-esque tweaks to his slice and volley, or look for tweaks to aid his serve? Yes. Would I work on calming down his behaviour when he loses points? Absolutely.

All this is not to say that mentality isn’t important, but rather, to highlight where mentality sits in the pecking order of success. All the top players have a passion and drive for the game. All have experienced a lot of success in their careers, but before we assume player X isn’t improving because they are ‘mentally weaker’, let’s put the microscope on their game and see why they might be losing points from a technical and physical standpoint first. Doing otherwise is accepting the mirage. Once we can see that players are dueling evenly, then the mental games begin; then we see a champion’s mind.

A supreme level of fitness is another component that I think helps a player maintain composure under pressure.

In Djokovic’s incredible 2011 season (where he started 41-0) he won 56% of points for the year.

For example, Davydenko leads Nadal 6-5 in their H2H, but trails Federer 2-19. Or just look at Nadal’s record at Roland Garros: that left forehand pattern is amplified big time.

Lleyton Hewitt was mentally one of the best ever, but he played the second half of his career in an era of better players. His mentality didn’t help when the chasm in tennis ability grew too wide.