Djokovic vs Alcaraz: AO Quarterfinal Recap

generation game — return strategies — attention — backhand slice

Novak Djokovic came back from a first set deficit and injury concern to defeat Carlos Alcaraz 4/6 6/4 6/3 6/4 in the quarterfinals of the Australian Open on Tuesday evening. The Serb extends his H2H lead over Alcaraz to 5-3 and will play Alexander Zverev in the semifinals on Friday.

Djokovic’s opening service game highlighted the serve tactic that was to prove pivotal in this match, three times finding a forehand error from the Spaniard’s topspin return of serve (twice on the wide slider on the deuce side). A sluggish start from Alcaraz was off-set with one-touch moments of brilliance, such as this lunging-stab-drop-volley from 0-30, but he was unable to save that game, spraying a plus-one forehand long.

At the other end of the spectrum, Alcaraz erased the early break with a backhand down the line winner off the back of a cagey and low 26-shot rally:

As I mentioned in a preview, it was interesting to see how Alcaraz’s game would translate to the cooler evening conditions in Melbourne (his opening four matches had been during the day) and the quagmire of facing Novak Dunlop Djokovic; a combination that has proven impossibly hard to hit through, save for a red hot Stan Wawrinka way back in 2014.

Sidenote: Is Novak going to win the title seventeen years after his first AO title? Wild.

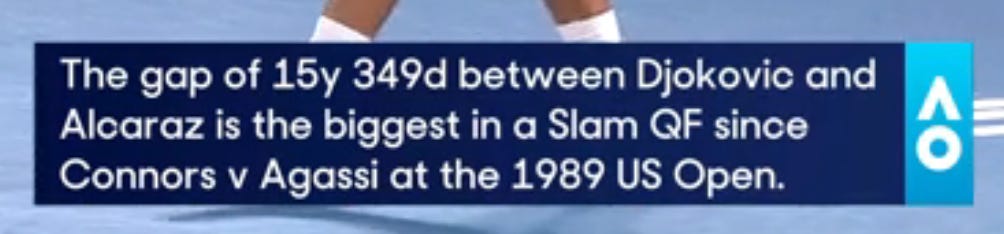

Midway through the first set we were reminded of the generational gap between the pair:

If you go watch some highlights of that match, the generational difference in technique is stark. Agassi had the new ‘extreme’ semi-western grip and topspin power tailored for the new oversized racquets, whereas Connors punched his way with wooden strokes duct-taped to a spacey graphite frame of the day.

But there was no such visual dichotomy in this match, in terms of strokes or even movement. Remind me again, where has tennis evolved lately?

I’ve often remarked that tennis has kind of stalled in terms of development for the better part of 20 years. The racquets aren’t all that different.1 Luxilon was being used in the mid 90s. Guys have been cross-training since Lendl and then Courier. Paradorn Srichaphan was sliding on hardcourts in the mid 2000s. “Marginal gains” might be the label that describes today’s taller, faster, frenetic game, built on lighter racquets and even-finer tweaks to strings, but it’s still unclear to me if this is meaningfully better than the tennis of Federer 05, or the subsequent baseline attrition era we witnessed circa 08-14.

Much has been said of Carlos adding five grams of lead to the throat of his racquet in the off-season, which his team felt helped the Spaniard on return, and which some have been saying will give him more power, but that’s assuming he is swinging his now-heavier racquet just as fast as his lighter racquet:

"If a heavy and a light racquet are each swung at the same speed, the ball will come off the heavy racquet faster because the heavy racquet has more momentum and more energy that it can transfer to the ball, and it will lose less energy. However, heavy racquets might not be swung as fast as light racquets. There is, therefore, not a big difference in maximum power between heavy and light racquets. In general, racquets tend to be swung at medium to fast pace rather than maximum possible speed because players need to make sure the ball goes in. In that case heavy racquets offer a bit more power and control than light racquets because they don’t need to be swung as fast to achieve the same ball speed."

— Technical Tennis: Racquets, Strings, Balls, Courts, Spin, and Bounce, by Rod Cross and Crawford Lindsey

Has Alcaraz’s power been up this year? On serve it appears it has been, but that could also be due to a motion tweak. Specific to groundstrokes, I couldn’t discern any meaningful difference in his baseline power, perhaps due to the quality of Djokovic’s ball.

But back to the match, Alcaraz did seem to show signs of lessons learned, anticipating this crosscourt heater from Nole, and ripping it back sharper for the sit-up line ball:

Furthermore, given the quality and speed of Djokovic’s second serve, I wasn’t surprised when I saw Alcaraz drop back at 4-4 deuce and play a trademark North-South point from return:

It’s been a feature of the Alcaraz game since he first came on tour.

Alcaraz would break in that 4-4 game as Novak went off court for a medical timeout to treat an issue to his upper leg. After the break Alcaraz served out the first set to love with his best serving of the match.

With Novak down a set and physically hampered, I was thinking I was going to get an early bedtime.

Au contraire.

This is where the dynamics of the match flipped.

Djokovic, forced to go on the offensive, started to take big cuts on return in the 1-0 game of the second set:

It paid off, and Djokovic was quickly out to a 3-0 lead in the second set.

“I think we have got to remind ourselves. We’ve seen Novak with some body issues right throughout the course of his 10 wins here, and he’s still been able to find ways of winning, hasn’t he? So he’s very durable in these situations.”

— Roger Rasheed

For all it’s comparisons to the sweet science, tennis is a far more delicate sport compared to boxing. The fine-motor-skills are on a whole other level. Add in the possibility of ten-minute-plus injury timeouts, and you have yourself a completely different mental hurdle. In the words of Mike Tyson — himself a big Djokovic fan:

“Everyone’s got a plan until they

get punched in the mouthface a wounded Djokovic.”

It’s one of the most interesting dynamics in sport.2 While you gain a perceived physical advantage facing a hurt opponent, in tennis, you can lose the upper hand mentally. I’d say two of the most studied topics within sports psychology are motivation and attention. The former requires no real analysis here: in a grand slam quarterfinal between two generational greats, it is safe to say that the intrinsic motivation was high in both. But attention is where their mentalities diverged. Djokovic, forced into an aggressive strategy and freed from the expectations of winning, was able to focus his attention on simply crushing the ball. Alcaraz, on the other hand, had the added pressure of two new strains of thought. The first was the imagined fallout of losing to an injured opponent. The brain doesn’t need much of a prompt in this regard and is quite adept at churning out scripts of disaster. The second was tactical in nature. Alcaraz had to consider how he should adapt his game to this new, injured Djokovic. Make him run. Hit more drop shots. He’s 37 years old. No, just keep the ball in play. Don’t miss. Make him run. He’s 37 years old.

The dichotomy of thought is kind of like the midwit meme.

“He was trying to play at some point quite a few dropshots and to make me run. I've been in situations, as well, where opponent's are struggling with injury, but keep going. The opponent is going for everything, and then he's staying in the match. Then all of a sudden as the match progresses, the opponent feels better. You're starting to panic a bit with your game. I understand the feeling.”

— Novak Djokovic post-match

But it would be a mistake to think that all great players are mental Jedis able to block out all other notions. I’ve always contended that you need to be good enough to play in spite of whatever thoughts enter your mind.

“In life and sport we’ve got to focus in bringing people’s competencies out, not searching for this idea that we have to be confident before that can happen. You know, confidence actually follows competence. Do you want a competent team or a confident team?”

— Jonah Oliver

This is where Alcaraz simply wasn’t good enough. Against an all-time great, especially one as cagey as Djokovic, you have to be ruthless, and he wasn’t.

The most important point of this match was the backend of the second set from 3-3, once Alcaraz had neutralised a resurgent Djokovic by getting back on serve, and when Djokovic was still very much in a big-swinging mood and uninterested in hanging in long rallies.

I also think it was a tale of two backhands.

If you rewind the game tape you’ll see Alcaraz miss two very make-able backhands to start the 3-3 Djokovic service game. The first is a passing shot from near centre, and the second a return of serve. Djokovic goes on to hold. Alcaraz holds easy again because Djokovic is still largely standing and slashing at balls. At 4-4 Alcaraz curls a forehand pass up the line to go 0-15 on Novak’s serve. He then gets a look at a second serve and tries a sneaky kind of SABR:

That was a moment. You even see Novak hobble after fending off the approach. This is where I feel Alcaraz needs to develop that ability to take a guy to deep waters and put him in the hurt locker for a few minutes. Make him have to hit four, five, six good balls to earn a point while the idea of retiring is still going through his opponent’s head. Or just do your normal North-South return but start deep and get a quality strike to start the rally. Instead, Nole had to play one instinctive shot and was back to 15-15. He goes on to hold (again with an Alcaraz backhand error at 40-15).

Now serving to stay in the set at 4-5, Alcaraz starts the game with a three-metre miss on the backhand:

Novak then slashes a forehand inside-out winner off a slightly short and highly flighted ball from Alcaraz, who was looking to change the rhythm.

0-30.

Then Novak minces another backhand return, and Alcaraz fails to fend it off with his own backhand.

0-40. Set point Djokovic.

The delta between Djokovic’s backhand and Alcaraz’s backhand at the business end of this set was huge.

I’ve been vocal about Alcaraz’s technical backhand change being a net negative, but the footwork on these misses were more to blame, and likely driven by the pressure of playing an injured Djokovic.

In hindsight that was where Alcaraz took his foot off the throat.

The painkillers kicked in during set three, because the movement of Djokovic started to come back, and the tennis from both reached the familiar quality we have become accustomed to seeing in this great rivalry.

The difference was mainly in the serve/return dynamics; Novak was way better in both departments. He targeted Alcaraz’s forehand return all night, and often went big on the second serve when Alcaraz was looking to use more crush-and-rush strategies — a feature of his game this week in prior rounds.

At 2-1 we got a carbon copy return from earlier. Again, this serve is nowhere near wide enough, or fast enough to trouble the greatest returner of all-time in an aggressive mood:

And when Alcaraz was returning, he wasn’t getting enough heat on his ball to stop Novak from taking command of the point. Djokovic is usually pretty average in the speed and spin rates charts, but it is his ability to change direction and play into smaller targets that make him an absolute monster:

Tennis Insights released a cool new chart that showcased how much more dominant the Serb is compared to the tour average when it comes to hitting his groundstrokes down the line.

While so many players tend to build their forehands from the ad-side mound, crushing inside out/in with huge spin and power, Djokovic is kind of the opposite. He eschews power and spin for control. His ability to hit small targets from tough positions and while on the run means he often ends up hitting more forehand winners than his forehand-specialist opponent anyway.

If there was a shot that Alcaraz had repeated success with from the ground, it was with his heavy and angled crosscourt forehand, stretching Novak wide of the singles line.

The problem was, Djokovic’s rally ball was of such pace and depth that it was hard for Alcaraz to find the time to load up on such a shot. Related to that, notice how Alcaraz played a backhand slice on the first ball? I think one of the best ways to neutralise an aggressive Djokovic is to slice to him. It’s by no means a solution, it just makes your problem smaller. Nole’s ability to generate pace and spin from low and slow contact points is probably his most obvious weakness (if you can call it that). We’ve seen Medvedev and Gilles Simon have success with low and slow tennis to Djokovic, hell, slice aficionado Dan Evans scored a win over Djokovic in Monte Carlo a few years ago (and Stan Wawrinka — a man who went 3-0 versus Djokovic in slam finals — was a block master on the return of serve. I don’t think that is a coincidence).

The Serb excels at linear hitting around the waist, so if you get it low and force him to sacrifice his racquet speed to vertical lift/spin generation, that slows his ball down, and it buys Alcaraz time to load up on his shots a little more with his body.

Even the point that Alcaraz played to break back had this tactic unintentionally woven in. He plays a defensive forehand short cross, and Novak doesn’t hit his line ball well enough to approach, getting caught on the baseline as he backed up to a backhand. It created the time for Alcaraz to find a forehand on the next ball, and from there he controlled the rally:

sidenote: go back to the start of this now long-ass post and note that the first break in set one also had a slice to help setup the slower trades.

Back on serve at 3-4, Alcaraz again missed two plus one balls: a forehand (close) and a backhand by more than a metre to get broken. It must be said that Novak did a lot of the heavy lifting here on the other points, playing with relentless depth and intensity, moving like a not-37-year-old, and overall just taking Alcaraz’s best shots and giving them back with incredible quality.

Djokovic served it out at 5-3, the set point being one of the best of the tournament so far.

He wasted no time at the start of the fourth, breaking Alcaraz immediately. Alcaraz and co. appeared to have no idea on how to solve the Djokovic serving riddle:

I felt overall that Alcaraz tried to come over too many forehand returns when standing closer. He could have chipped more of these — even against an aggressive Djokovic. Alternatively, he could have tried to return from much deeper, like he often does on clay:

This would have stopped Djokovic’s effectiveness with the faster second serves, and it’s kind of in the Alcaraz wheelhouse to return from here anyway. For all the talk of the new on-court coaching pods, this one seemed like a missed play from Juan Carlos.

Anyway, Djokovic’s serve cooled off in the fourth, and at 2-2 Carlos earned a break point. He did all the right things, but Djokovic did all the right things, too, outlasting his younger foe and forcing an error (how many times has he done that, as opposed to hit a winner, in big moments over the years?). Here’s the end of it:

But credit to Alcaraz, the kid is a fighter. He kept coming, and he did start to use the backhand slice way more in this game. I liked this tactic, which only lacked the final touch of execution:

If you rewatch the 2-1 and start of the 3-1 game, you see how Alcaraz’s slice slows down the tempo and helps buy him time, and when he has that extra bit of time he is a completely different player.

Midway through the fourth set Alcaraz started to get more looks on return as Djokovic’s serve fell away a touch and the Spaniard upped his ground game quality. He was getting to 30 consistently, and had no better chance than at 3-4 0-30, before Djokovic did this:

But Carlos still got two looks from 15-40. The first was an unfortunate time to shank a forehand, the second was snuffed out by a quality wide-serve-and-volley point from Djokovic.

He rode the same quality of ball-striking all the way to the end, converting on his first match point on a running forehand error from Alcaraz.

In these cooler evening conditions, the standard return positions of Alcaraz, the kick-serves of Alcaraz, the backhands from the baseline, it was all just batting practice to Nole. Carlos needed to mix it up more with his return position, he needed to change the speeds and break the rhythm of the linear rallies more. Having been rope-a-doped between the points with an injury scare, he needed to rope-a-dope Nole back during the points. He did this to Sinner last year in Indian Wells after getting out-hit in the opening set. Look where he was returning from:

An excerpt from that piece:

“There’s always a certain tempo, place and height that players are comfortable playing in, but Alcaraz is the tennis equivalent of a jazz player, able to seamlessly change his spins, depths, and positions on the court in a bid to change the rhythm of a match. The more he leans into that feature, the more he can take his opponent’s out of theirs.”

Monster effort from Djokovic, who finds himself in a 50th grand slam semifinal. If the leg issue isn’t major, I’m thinking Sinner and Djokovic would make one hell of a final, given the beatdown Sinner gave de Minaur just now. The two best guys at the bread-and-butter elements slugging it out over five sets. Let’s see what Shelton and Zverev can do come Friday.

For Alcaraz, there are questions (at least from me).

Why all day matches in the first four rounds? You know you gotta step out at night to win this thing. Having no night match prep, whereas Djokovic had played his two previous matches at night on RLA, couldn’t have helped.

This is twice now (Olympics) Alcaraz has failed to make inroads on Djokovic’s serve. There was an obvious play here to step way back and give a different look, but we didn’t really see it. On that same note, what is the serve play for Alcaraz on these deader hardcourts? The kick was kind of man-handled by Djokovic tonight. He needs to develop a 3/4 slider.

I still have a big question mark over this new backhand technique. Out wide, up high, without your legs, I’m not sure it’s better

Be back soon. HC

"All racquet performance technologies boil down to two things—altering the stiffness of the frame (and stringbed) and the amount and distribution of weight. That’s all. These in turn determine the power, control, and feel of a racquet. There are seemingly hundreds of technologies in the marketplace, but virtually every one of them is in some way directly or indirectly addressing weight and stiffness. But weight and stiffness can be combined in so many different ways that each racquet feels different from the next. It all depends on how much weight you put where and how stiff that material makes the frame."

— Technical Tennis: Racquets, Strings, Balls, Courts, Spin, and Bounce, by Rod Cross and Crawford Lindsey

Are there examples in other sports where facing a slightly injured opponent can actually make things harder for you?

Great analysis as always!

Especially liked how you highlighted the crush and rush as the crucial moment of the moment in the second set. I shook my head in disbelief at such poor decision-making on such an important moment and thought I was seeing Rune. Tweeted about it immediately. Other than that, a pretty normal Djokovic win in those conditions

I wanna quickly have a word on Sinner because to me he really is a 2.0 version of Djokovic...The guy consistancy, hard court dominance, court coverage, backhand, return of serve ect remind me of the great nole but in addition he has the fire power that nole doesnt have... Hugh, you have highlighted in this article the very few weaknesses (if we can say that) that novak always had which is dealing with balls with no pace or spins and he has to generate it himeself ect but in the case of Sinner ( who we can say really reached his prime in 2024) the guy seems to have no weaknesses cause he has the qualities of novak but as well huge fire power and no difficulties whatsover the accelerate balls or run around his backhand...If novak ever play yannick in the final if he beats zverev, I would put my mortgage on Sinner taking this as he is an upgraded version of novak ( not to say prime novak was worse but more like 37yo nole cant defeat his style). Anyway would love to see the match up with an healthy novak to see what kind of tactic he would put in place to expose some "weaknesses" out of sinner's metronomical game.