Carlos Alcaraz dethroned defending champion Novak Djokovic 1/6 7/6 6/1 3/6 6/4 to claim his first Wimbledon title and second grand slam (US Open 2022). In a match with several swings of momentum, the Spanish phenom stayed the course for 4 hours and 42 minutes in blustery conditions, sealing the famous victory on his first match point.

First Set

While the computer rankings had Alcaraz at 1, Djokovic was eager to dismiss any notions that he isn’t the world’s best player. The opening two service games highlighted a common theme that had often been the difference between Djokovic and the field. While Alcaraz showcased his attacking prowess in the opening points, bringing Djokovic to his knees and generating a break point…

…the young Spaniard was unable to capitalise on his chance.

The very next game Djokovic made no such error, and he seemed intent to pick up where they had left off in Paris: with the running forehand.

I felt that the wide forehand was again going to be the shot that would steer the fate of this match. While Alcaraz and many other top prospects have a dynamic, powerful, and “big” forehand from the set position, the Serb eschews offense in favour of directional control. Like an elastic rubber band, the unique properties of his game are best displayed when stretched:

It’s this kind of shot that makes his forehand so good—and underrated—in my opinion. No one else has that return, and it rarely results in a winner, that salient and bite-sized chunk of entertainment that crowds crave, but rather, forces an error through depth and positional pressure. It’s a subtlety that can’t be truly appreciated until you actually play him I suppose.

In contrast, Alcaraz is something different entirely, and although he was down 5-0, I don’t think this reflected how close the match had been up to that point. There were glimpses of his brilliance that make his talent undeniable:

Djokovic: “He surprised me, he surprised everyone in how quickly he adapted to grass this year, because he hasn’t had too many wins on grass and obviously him coming from clay and having the kind of style that he has, you know...the slices, the chipping, the net play. It’s very impressive.”

Second Set

Sport is often compared to the brutal and competitive elements of nature and evolution, the “survival of the fittest” and all that. Turns out that is a misquote. It is actually better summarised as “the one that is most adaptable to change.”

And it this quality that I think defines the great players. Djokovic shared as much in his post-match press conference:

“I think people have been talking in the past twelve months or so about his game being of certain elements of Roger, Rafa, and myself. I would agree with that. I think he’s got the best of all three worlds. He’s got this mental resilience and mental maturity for someone who is 20-years old. He’s got this Spanish bull mentality of competitiveness and fighting spirit and incredible defense that we’ve seen with Rafa over the years. And I think he’s got some nice sliding backhands that have got some similarity with my backhand and defense and being able to adapt. I think that’s been my personal strength for many years, and he has it too. So I haven’t played a player like him, ever, to be honest. Roger and Rafa have their own strengths and weaknesses…Carlos is a very complete player. Amazing adapting capabilities that I think are key for longevity and a successful career on all surfaces.”

What Djokovic now lacks in youthful energy, he makes up for with experience. This version of Djokovic, at 36 years of age and 23 major titles, isn’t the fastest, fittest, or most consistent version we have seen, but he is the most complete. The serve is more precise, and elements of his game that were awkward and rough-edged in his youth have now been polished in the competitive grit of the tour. So while Alcaraz was showcasing his own quick adaptions to grass—with his block return, his slice backhands, and an overall calmness in his movement—he was still being denied when small openings presented themselves, like this brilliant point at 0-30:

The very next point Alcaraz was denied again by the Serbian’s defense. Djokovic just takes you to deep waters. He takes your best hits and then turns the screws with precise, measured hitting. He asks questions of you in both corners over and over again. However, with ever more consistency, Alcaraz had the answers. Note how measured Alcaraz’s own hitting and movement is in this point:

And if you’re watching that and not seeing it, then cast your eyes back to their recent semi-final match at Roland Garros. There, Alcaraz’s forehand was torn to shreds as he attempted to unload with power even when rushed and out of position. Here’s an example:

Now let’s focus in on some of the subtleties of Alcaraz’s movement on clay versus grass in the running forehand. These side-by-side clips are just isolated shots from the two clips just above.

Note how there is a “running through” the ball on grass here. He hits and lands on his left foot first on grass, rather than the typical open stance forehand that unloads, or “jumps” into the ball with the right foot and lands with the same right foot. While tennis is taught from the “ground up”, that is, you use your legs to drive your hips and then into the smaller muscles of the arm and wrist, as always there is a nuance to be had in different situations. The Alcaraz forehand on the left has more leg drive and therefore more rotation, and that means more moving parts (or the same parts moving faster). It’s the typical forehand on clay and hard courts, but against Djokovic’s phenomenal redirection it rushed Alcaraz into errors. What we see on the right clip is a great example of how Alcaraz has adapted his movement and forehand to the lower and quicker grass. Here we see him willing to absorb the shot and simply redirect it back. By running through the shot and finishing on his left leg he is able to stay lower and keep his upper body quieter. The emphasis is on timing the ball, rather than hitting with power, and as a result, the forehand side of Alcaraz was much tighter in this match than it was at Roland Garros. By my count the Spaniard actually finished with fewer forehand errors than Djokovic, and you can see how the match scores ebbed and flowed with the forehand:

It was pretty cool to watch in real-time as Carlos patched a weakness and blended so many elements together. The point below is a great example:

There are ghosts of many players in that point. The chip forehand return is Wawrinka-esque, the lasso forehands like Nadal, carved slices for the purists, drive backhands like his opponent, and that final Federer-esque forehand that he runs through up the line. Perhaps this was the most bullish sign for me; Alcaraz was winning long rallies by subtle change-of-direction with his own forehand. That was not his MO, like, two weeks ago.

The second set tie-breaker decided the match, in hindsight. Djokovic broke out to a 3-0 lead, but Alcaraz found some spot serving to claw back to 3-3. At 6-5 and with a set point to Djokovic it was a virtual match point. Djokovic was riding a long tie-breaker win streak, he was on grass, he was up a set. We’d seen this movie before. And then Djokovic missed two regulation backhands in a row. When it rains it pours. Down set point now, Djokovic serve-volleyed out wide to the Alcaraza backhand:

And just like that, we had a match on our hands.

Third Set

Alcaraz broke immediately to start the third set. Again, the Spaniard was holding his own in the forehand exchanges, then finding ways to draw errors out of Djokovic:

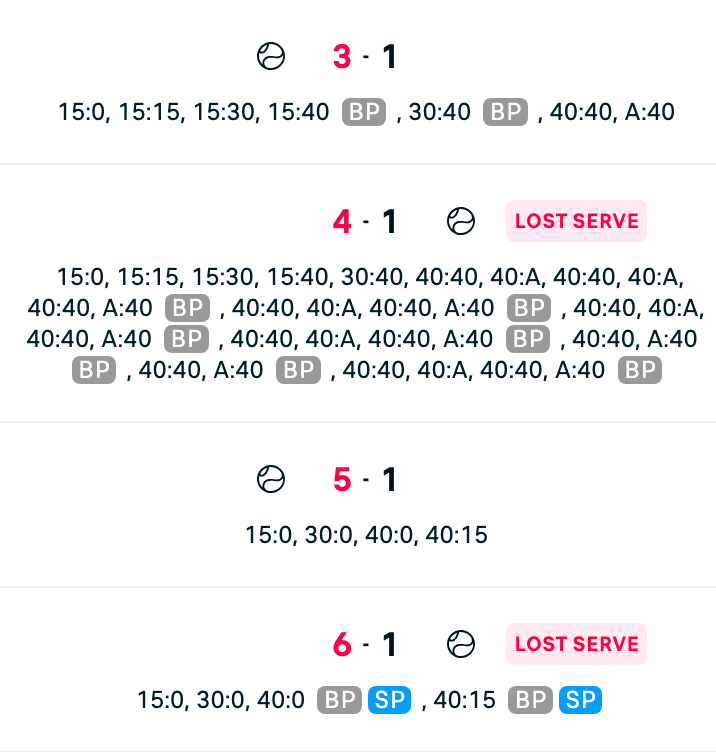

At 3-1 and with Djokovic serving down a break to hang on in the set, the pair played out a pivotal 26-minute game that killed Djokovic’s will to battle for the third set. Check out the point-by-point:

This was a set where Djokovic’s forehand really went off. Alcaraz threw in some higher and slower balls, and coupled with the wind, it wreaked havoc on Djokovic’s timing.

Amazingly, after three sets of tennis Novak Djokovic had only managed two aces against Alcaraz. He wouldn’t hit any more in the match.

Fourth Set

At 2-2 and 30-15 Alcaraz missed a high forehand volley that would have given him 40-15. Instead, he dragged it wide. Often times these higher volleys are harder because it’s much easier to overplay and swing too much on them.

And despite some brave second serving from Alcaraz, the wide forehand return from Djokovic struck again at deuce. It’s so effective if you can attack a player’s serve because even great movers and defenders like Alcaraz are still inside the court and recovering; you neutralize their footspeed and catch them out of position:

Djokovic would break serve at 2-2, and he did well to steal ground in this set:

With momentum on his side the pair went into a fifth set. Djokovic’s last loss in a fifth set at Wimbledon was in 2006.

Fifth Set

Djokovic served first in the opening game and boy was it a heater. Too many great points to show. Here’s one with some locked wrist backhands emphasised (sidenote: look closely on the last ball and you see Alcaraz switch from continental — as he’s anticipating a move to his backhand — to forehand grip with just the hitting hand. Just flicks it around in the palm of his right hand then whips the forehand):

Djokovic held on and then immediately put Alcaraz’s serve under pressure. At 15-30 Alcaraz served tee and feathered a short backhand volley crosscourt. In theory this is a great play against a deep returner who goes through the middle like Djokovic does, but it’s ridiculously hard to do, let alone in a fifth set in the Wimbledon final. Even Novak smiles.1

Something else starts happening in this fifth set. Alcaraz finally starts threading the drop shot. By my count, Alcaraz had gone 1/6 on drop shot points in the first four sets, but in the fifth he would go 5/6. Unlike most players, Alcaraz uses his drop shot more on his forehand side, and it’s usually a good barometer for how well he is hitting his drive forehand (one complements the other), which was starting to catch fire:

I’ve often noted how Djokovic builds pressure in subtle ways, using depth and line balls rather than outright power or rushing:

“Corner defence married with controlled depth and subtle change-of-direction may not make for good highlight reels, but it allows him [Djokovic] to effortlessly tear apart quality top-20 opposition without getting out of mid-gears.”

But Alcaraz’s pressure is more akin to Federer. It’s the relentless attack from every part of the court, and then using every part of the court to expose his opponent. This is the unique quality of Alcaraz’s game; he’s the first player to thread every inch of the court so willingly on offense and defense, with the ball and with his movement.

The added bonus for tennis is that this makes him a highlight machine. In an era where our attention is fought for by a saturated sports and media market, Alcaraz’s dynamic and colourful game will no doubt draw new fans to tennis:

After Federer’s retirement I wrote a piece on the Swiss legend. An excerpt:

“…part of his [Federer’s] appeal was also the aggressive forecourt nature of his game in an era where, even for casual observers, implicit in that style was a degree of risk that was courageous and admirable. Wandering from the mode of topspin baseline attrition is usually a sign of fatigue or desperation, but Federer managed to splice power and spin with finesse in a way we hadn't seen before. Looking back, it was always going to fall short of the consistency of Nadal and Djokovic’s baseline games in terms of winning. But crowds care about more than just winning.”

Alcaraz is in that Federer mold. If there has been criticism of some champions, it’s often that they are too clinical for casual fans. Sampras’ cool and serve-lasered game was often branded as such, and juxtaposed against Nadal and Federer, Djokovic has probably come under a similar framing. It’s important to remember that sports are in the entertainment business at the end of the day, and players like Alcaraz are a boon for bottom lines.

To blend excitement with winning is a talent in itself because so often their interests run counter to one another. Ali, Jordan, and Woods had that quality about them and transcended their respective sports. Kyrgios achieves the former at the expense of the latter. Alcaraz has certainly found the balance, seen here serving for the biggest title of his life:

And on match point, with the winds of youth at his back and a lack of scar tissue that tends to accrue with tough losses against a rival, Alcaraz finished the match with that all important forehand hammer:

Although not the highest quality final we’ve seen (the wind and swings of momentum made that difficult to award), the fifth set was incredibly good tennis given the stakes, the conditions, and the fatigue that must have surely been felt by both. I think it’s important to emphasise how well Djokovic made Alcaraz play to win that title. Despite strategically throwing games in the third and looking in poor form for short stretches, the fifth set was gold-standard Novak, and Alcaraz beat him with forehands, backhands, slices, drop shots, volleys, lobs, and serves. He was simply too good.

I had Alcaraz with 21 point-winning forehands to Djokovic’s 20:

Even on the backhand, I had Alcaraz with 11 point-winning backhands to Djokovic’s 7. For backhand errors, I had 20 for Alcaraz, and 18 for Djokovic.

Here’s a surprise: Alcaraz served 9 aces to Djokovic’s 2!

As always, Djokovic was gracious in defeat, and in the post match press conference was full of praise for Alcaraz:

Novak Djokovic: “Amazing poise in the important moments for someone of his age to handle his nerves like this and be playing attacking tennis to close out the match the way he did. I thought I returned very well but he was just coming up with some amazing, amazing shots.”

Some quotes from Alcaraz:

On confidence not being necessary for great performances:

“Probably before this match I thought that wasn’t ready to beat Djokovic in five sets, an epic match like this. To stay good physically and mentally, for five hours against a legend. That’s probably what I learned about myself today.”

On being compared to some fusion of Nadal, Federer, and Djokovic, by Djokovic:

“It’s crazy that Novak said that. I consider myself a really complete player. I think I have the shots, the strength physically, the strength mentally. Probably he is right. But I don’t want to think about it. I want to think that I am Carlos Alcaraz.”

On winning the all important second set:

“In the second set I knew that I was going to have my chances. I had to stay there and wait to be up and close on the score. After winning the set it was really good for me, because if I lost that set I probably could not have lifted the trophy.”

Alcaraz is now the third youngest ever men’s Wimbledon Champion (behind Becker at 17 years, and Borg at 20 years):

“It’s a dream come true for me. Wimbledon Champion is something that I really wanted. I didn’t expect to get it so soon.”

Alcaraz used this play to great effect against Medvedev in the Indian Wells final also.

This is the best writing on tennis I've seen in some time. Too often, the big writers/commentators/podcasters eschew technical analysis (bc they can't do it) in favor of narrative. That's all find and good, but this kind of smart tennis writing is really rewarding for fans who have a grasp on the game.

Suggestion for a future article: The gap between Alcaraz and the young field feels massive now. I'd love to see some analysis on how Sinner/Tsitsipas/Zverev/Rune etc. lack adaptability. So much talent and athleticism but seemingly so little intelligence/nuance to their games.

The consistency bump on Alcaraz's groundstrokes was essential, especially in the irregular conditions of the final. Great analysis and focus on the forehand adaptations to improve ball control on the run instead of out-blasting Djokovic (as we saw in the RG duel, you're absolutely not going to have a fun time trying to overpower Novak with raw strength). I could feel not just the technical changes and the talent to adapt to the conditions, but also the grit that it takes to keep executing these controlling 60%-70% power shots when you know that you're likely receiving another corner / court-side pressure shot when the ball comes back. After a few seconds in that situation, the average player can feel the temptation of a desperate low-percentage bailout shot emerging in their mind from the pressure and exertion.

I think the backhand side also was better than usual in analogous fashion. He did not overhit that much and even when he was putting more power in them it was in the form of extra linear speed/acceleration/pushing with the whole chain instead of "rotational whippyness" at the end, producing safe high-margin aggression instead of blazing balls smoking the grass somewhere near the corner of the court. Again, great preparation and execution since control, consistency and direction are dangerous enough on their own in grass (as proved by the regular Djokovic sweep after the Fed era).

At a few critical moments in the match, we could also see the champion factor, the seventh gear, the ability to execute the impossible when no other option is left. And the heroics adapted as well; they were there not just in the form of side-to-side hopeless chasing sprints (though there a few of those as well), but also as a set-winning outside-in stretched backhand return or as a flying drop volley when serving for the win. That's stuff from myths and legends.