Andrey Rublev lost his quarterfinal Roland Garros match last week to Marin Cilic in a fifth-set super-tiebreak. It was Rublev’s fifth slam quarterfinal and his fifth defeat. In the press conference after the Cilic match Rublev’s performances in the slams were questioned, and the Russian attributed his 0-5 record to his mental game:

Reporter: “Andrey, you have a fantastic record on the tour, but at Slams you just seem to get to the quarterfinals and not be on. Do you know why that is, or is it just a matter of time for you?

Rublev: “No it’s mental. Everything’s mental. I couldn’t manage the emotions the previous times and now was the closest ever I was able to go through and be in semis, but again, the same thing. I didn’t manage the emotions.”

In a prior piece, I made the argument that Rublev’s issues were not all mental, or more accurately, that they could largely be explained because of his tennis and his opponent’s tennis. An excerpt from that piece:

“In Rublev’s case, I’m not sure mentality is where he is really lacking. Let’s keep in mind he’s top-10 in the world. Sometimes taking the next step isn’t possible because your peers just take bigger steps (ask Andy Roddick). He works hard and has won plenty of titles. The players ahead of him are simply a little better at tennis—for now.”

It’s easy to accept the mental narrative when the player in question admits as much, but if we step back and analyse each of these losses, to put these performances down to Rublev’s mental game does a disservice to his opponents (who were all higher-ranked at the time except for Cilic) and assumes his game is on par with these players when an aggregate look at each match-up suggests otherwise. The five quarterfinal losses:

2017 US Open Nadal def. Rublev 6/1 6/2 6/2. A 19-year-old Rublev got outclassed in this match. Simple as that. Nadal hit more aces, fewer double faults, more winners, fewer errors, and won a monstrous 63% of points. Looking at the highlights you get a sense of just how physical it is playing Rafa; he took Rublev’s fearless teenage hits and just chewed them up. One interesting technical observation from this period in Rublev’s career: his backhand take-back appeared longer and more in line with a traditional full-turn/buttcap facing the opponent. More on that later.

2020 French Open Tsitsipas def. Rublev 7/5 6/2 6/3. While Rublev had beaten Tsitsipas in a tight three-setter in Hamburg just prior to the October-held French Open (due to Covid) Tsitsipas was the higher-ranked player, the bookie’s favourite, and on balance a better clay-courter than Rublev. I can’t find meaningful highlights or a full replay of this match, but Tsitsipas dominated on first-serve (both made 64% of first-serves, but Tsitsipas was winning 80% of his to Rublev’s 66%) and won 63% of second-serve return points to Rublev’s 32%. Their H2H is close, with Tsitsipas leading 5-4, and I am willing to concede that Rublev may be a better player than Tsitsipas on a hard court right now, but on clay, Tsitsipas leads their H2H 3-1, has more big clay titles, and has performed better at RG every year save for this year’s edition.

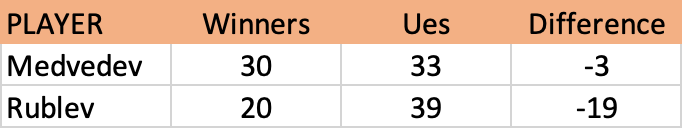

2020 US Open Medvedev def. Rublev 7/6 6/3 7/6. Again, Medvedev was the higher-ranked player and the strong favourite. I replayed the full match and took some stats. I tracked the winners and errors of each player’s forehand and backhand when under pressure/moving to that side, and when set in position from the baseline. Short ball winners were not counted. I prefer these metrics to the reported winner/error figures as this cuts the noise of easy putaway shots and puts a microscope on a player’s ability to handle pressure from the back of the court. I also tracked how many serves went unreturned on first and second serves.

We can see a huge difference in how many free points Medvedev got on his serve compared to Rublev (Medvedev only hit 2 more double faults as well). 16 more free points to be exact. Interestingly, that’s also the difference in total points won for this match (90 to 106). Off the ground, a few tendencies were evident to me across all three sets.

Medvedev defended off his backhand far better; it was very hard for Rublev to get Medvedev in a position where he had to take his left hand off the racquet. In contrast, Rublev often resorted to the chip when he was forced to move to that side more than a couple of steps, and it allowed Medvedev to dictate a lot of rallies and hit more winners overall.

Medvedev made a lot of uncharacteristic unforced errors in the first set (and probably should have lost it) but his serve was so much more dominant.

Medvedev hit 17 backhand winners to Rublev’s 2. This isn’t that surprising—Medvedev has a better backhand for sure—but what I think hurts Rublev is his lack of variety on the backhand side; he doesn’t defend as well on that side, but he also doesn’t attack as well either. I’ve written about the technical limitations that I think hold back the Rublev backhand before, but his backhand is still very good, he just doesn’t hit many line balls with it. However, what was interesting (and the same thing held for the Cilic match) was that Medveved completely out-winnered Rublev on the forehand side (7 to 16). I think Rublev’s forehand is one of the best in the business—better than Medvedev’s—but he didn’t create the space to find an open court with his forehand and Medvedev didn’t offer many forehands either; Medvedev was happy hitting backhand cross and when he went line it was often to pull the trigger rather than change direction (which partly explains his high backhand error count).

In light of recent months watching Alcaraz, it’s painfully obvious how much better Rublev would be if he had a transition game or drop shot in his arsenal. Medvedev played from the stands and Rublev didn’t drop-shot or come in much, and when he did he didn’t look completely comfortable/convincing. Nevertheless, he had good conversion rates at the net in this match when he did come in, and I think he needs to do more of it against the top guys ahead of him.

4. Australian Open 2021 Medvedev def. Rublev 7/5 6/3 6/2. I couldn’t find anything beyond the linked highlights, but similar to their US Open encounter, Medvedev hit more aces, more winners, fewer unforced errors, and won more return points on first and second serves. In the highlights Rublev did look to take wider stances with his serve to get a better open court with his forehand, and I think this was a smart change up, but I’m not sure that will ever be enough to get the odds in your favour; you need to be able to generate the open court off the ground so you can break serve. Again, if you watch those highlights, notice how wide Medvedev can take a two-hander; full-stretch and he still plays two hands and gets some interest on the ball.

5. 2022 French Open Cilic def. Rublev 5/7 6/3 6/4 3/6 7/6. Many thought this was Rublev’s turn to finally get over his quarterfinal hump. He was a slight favourite, but remember that Cilic beat Rublev in the third-round of the Australian Open only five months ago. I replayed their French Open match and took some stats.

After watching the replay of this match my general feeling was that the fate of this match rested mostly on Cilic. Rublev played his best and most aggressive tennis in the first set, and if Cilic found his best tennis he would have won this in four. Some thoughts:

Rublev generated 6 of his match total’s 7 break point chances in the first set. On numerous occasions this was off the back of backhands that went into the Cilic forehand corner.

Cilic’s serve earned him more free points, but also a lot of serve +1 short balls.

The biggest difference between these two was the quality of their second serves. Like Medvedev, Cilic hits a much bigger second serve, and although they posted comparable URS’s on the second ball, most of Cilic’s were just poor returns. As the commentator said in the fifth: “…that’s been the frustrating thing for Marin Cilic in this match. He’s just not been able to take advantage of the second-serve when its presented itself.”

Similar to the Medvedev matches, Cilic was content to trade backhands, and he looked to use his forehand into the Rublev backhand a lot. Although he posted a huge number of unforced errors, that in itself showcases that this match largely hung on Cilic’s strings; he was generating far more short balls and he caught fire in the back-end of the fifth set.

Commentators noted that of the eight quarterfinalists (Nadal, Djokovic, Zverev, Alcaraz, Ruud, Rune, Rublev, and Cilic) Rublev had the slowest average second serve speed of 145km/h (Ruud had the fastest at 154km/h). Cilic was repeatedly allowed to take big swipes on second serves and he started many return points on the front foot.

Rublev’s first serve was really good. In fact, I would summarise this match as an excellent first-serving display from both, but an average match off the ground. Again, though, Cilic (like Medvedev) out-served Rublev (10 more free points), and their total points won was Rublev: 170, Cilic: 175.

Key Takeaways

Rublev is a great player. He’s got a great first serve and a great forehand. He’s lost these matches to players who simply have bigger weapons and smaller weaknesses and their performances were pretty close to what was expected. Here are three key areas I think Rublev needs to improve if he is to take the next step and become a top-5 player.

The Backhand. As I have written previously the Rublev backhand—much like the Alcaraz backhand used as a comparison below—is a little whippy. It generates initial racquet-head speed with lag on the hitting side rather than gravity down the back. Can you have a great backhand like that? Absolutely. But as the video states, “there is a cost to everything, and the cost is going to be consistency and accuracy.”

There are certain technical landmarks that repeatedly show up in the best exponents of a given shot. As I have touched on previously with forehands and backhands, the best two-handed backhanders tend to hit two technical landmarks:

They get the racquet-tip upright in the power position.

They get the racquet-tip facing the back fence in a full turn (sometimes coaches encourage this by telling pupils to “show me the buttcap”).

Rublev doesn’t do either fully. His backhand is a shorter and wristier shot that does well holding the baseline and hitting cross court when in a set position, but he struggles to hit on the stretch, which is why I suspect he resorts to the slice much more often compared to great two-handers when he gets pushed wide. A higher, fuller take-back on the backhand (like the Djokovic video from above) does two main things that absolutely make it easier:

You can get more power on the stretch because you’re relying on gravity to get the racquet head initally moving rather than your wrist (gravity will always assist you consistently. Your wrists? Less so).

By taking a longer take-back you can play your backhand later. Something you need to do when on the stretch.

Now does he have to change his technique to get results? No. I think just committing to hitting more line backhands will give him better outcomes against these top guys, but sometimes your technique dictates your tactic; it’s harder hitting line with a wristier swing, and as I said in Part I “the screams of frustration that bubble over after missing the backhand may convey a mental breakdown, but the origins of these ‘mental collapses’ are often baked into the technique.”

The Second Serve. Rublev’s second serve is a liability for a top-10 player. He has spoken of this before:

“Also, I need for my second serve to be faster. It would be a huge advantage, since it would be harder to break me. In part, that is mental as well, because in practice I hit second serves harder and I rarely make double faults. But in the match, when I feel pressure, sometimes I am afraid to go for it, particularly when it is 30–30 or break point or advantage. Then I just push the ball in order to start the point. I need to say to myself ‘just do it’.”

Some of this is mental, but again, the best second serves (and servers in general) tend to start the swing on the front side of their body, as I have described in Serves and Returns:

“They tend to move the racquet quickly through a lot of space. If we look at great servers—not just tall guys, but brilliant servers relative to their height—we tend to see the racquet head maintain or build speed through the backswing (where the racquet head moves from right-to-left behind the players head).”

The one-minute video below demonstrates how Federer improved this aspect of his serve over his career.

Djokovic also made a similar change, and players like Kyrgios, Medvedev, and Lopez display similar actions on their serves. This is something I think Rublev could work into his serve over the course of an off-season and I think it would increase racquet head speed and, in turn, belief in his ability to hit a big second; more racquet head speed can generate more spin which helps with control.

Intangibles. Drop shots, slices, sneaking. Everyone’s probably familiar with some version of the ‘jar full of stones, pebbles, and sand’ metaphor. In tennis, the stones may represent the forehands, backhands, and serves. But the pebbles and sand make the jar ‘full’, and in terms of tennis, to make a player ‘full’ or ‘complete’ the drop shots, second serves, slices, and sneaking volleys are the pebbles and sand. They are things Nadal does nearly better than anyone (on top of having some rather solid rocks in his game jar) and it’s something that is sorely lacking in Rublev’s game. Working in better volleys and a forehand drop shot would make him far more dynamic as a player; Medvedev wouldn’t stand so deep and Cilic would probably bleed more errors. This is something that the top guys have improved over their careers, and Rublev needs to do this if he wants to be a better player; his game is big, but it isn’t big enough to warrant not having these shots.

Closing Thoughts

As hard as Rublev reportedly works, sports are not justice; his physical and technical limitations make his ascension to the ATP summit more difficult to a certain degree compared to the Medvedev’s, Nadal’s, and Djokovic’s. As it stands, I believe Rublev could make consistent semi-finals of slams if he made some adjustments to his tennis more than his mentality. I think he needs to hit his backhand line more, he needs to be able to defend his backhand better when pushed wide, he needs to improve his net game/intangibles, and he needs to hit a bigger second serve. Whether he can achieve that by purely changing his perspective and mental approach is yet to be seen, but my overall thesis of great tennis remains the same; the best performers tend to have technical similarties that allow this high level of tennis to manifest.

Rublev is currently number 8 in the world. He’s right where he should be with his current game. I would love to see him find another level—he plays the game with passion and works hard—but the guys ahead of him won’t give him a slam semi-final. He’s got to find a way to take it.

Below are some world-class backhands. Note the full take back and drop in each of these players. Rublev at the end for comparison.