Changing Technique

interference — mindsets — adaptations

“The world is quite ruthless in selecting between the dream and the reality, even where we will not.”

—All the Pretty Horses, Cormac McCarthy

The off-season weeks of December allow players a window to recuperate their bodies and tinker with swings and equipment. While the thesis of this newsletter is that technique plays an over-sized role at the top of the game and is often overlooked (at least in most media/commentary), pointing out cracks in a player’s strokes is still the low-hanging fruit of analysis and coaching. The million-dollar question is ‘How do you change technique?’

Beyond the biomechanics there is also the player’s traits to consider: their openness to change, their willingness to experiment through trial-and-error, their ability to adapt and integrate new movements, and their ability to stay disciplined with the change.

You have to get comfortable being uncomfortable.

It’s not a philosophy shared by all. Among some coaches there is a belief that the best path forward entails accepting weaknesses and focusing on a player’s strengths. Brad Gilbert is perhaps the latest example of this. He recently teemed up with Coco Gauff during her maiden grand slam run at the US Open this year. He made no technical changes to Gauff’s often criticised forehand throughout the North American hardcourt swing.1 Instead, Gilbert encouraged Gauff to make tactical changes (such as standing deeper to give her more time, and using more height and spin to reduce errors) and focus on the strengths of her game, such as her movement, backhand, and serve.

Darren Cahill also admitted that he overlooked Federer’s early promise because he was too focused on the Swiss’ weaker backhand:

"As an early coach, I was looking for areas that were going to hold him back, and I ignored a little bit the stuff that was going to make him great."

—The Master, by Christopher Clarey

However Federer’s backhand did develop into a reliable shield and a subtle weapon. To call it a glaring weakness only applied to specific matchups, such as against Nadal on clay, and it had little to do with his technique and a lot to do with Nadal’s extreme game style.

The current depth on the men’s tour does not allow for a baseline weakness if you want to occupy the world number 1 ranking or win grand slams. The five players who have managed to win slams this decade — Djokovic, Nadal, Thiem, Medvedev, and Alcaraz — boast groundstrokes that allow them to play offense and defense from both wings.

Before I continue I want to outline that changes can occur either by degrees or by kind. Changing technique by degrees is easier than changing technique by kind. Dominic Thiem shortening his swings in the 2019 season is an example of keeping the same kind of stroke and only changing it by degrees (i.e., swing length) to help him hold the baseline on hard courts. In the professional game it’s rare for technique to change by kind (e.g., changing from a one-handed backhand to a two-handed backhand, or going from an Eastern to a Western forehand grip) but there are plenty of examples of player’s changing by degrees. In fact, across the arc of a career it’s rare not to see a player’s technique drift by degrees.

Often technical drift occurs unconsciously. Perhaps a racquet change, or the speed of the game, forces a player to make adaptions without even knowing it. It’s not always for the better. However, I would wager that many players are: (a) aware of their weaknesses; (b) working on changing them; and (c) achieving minor tweaks with deliberate practice.

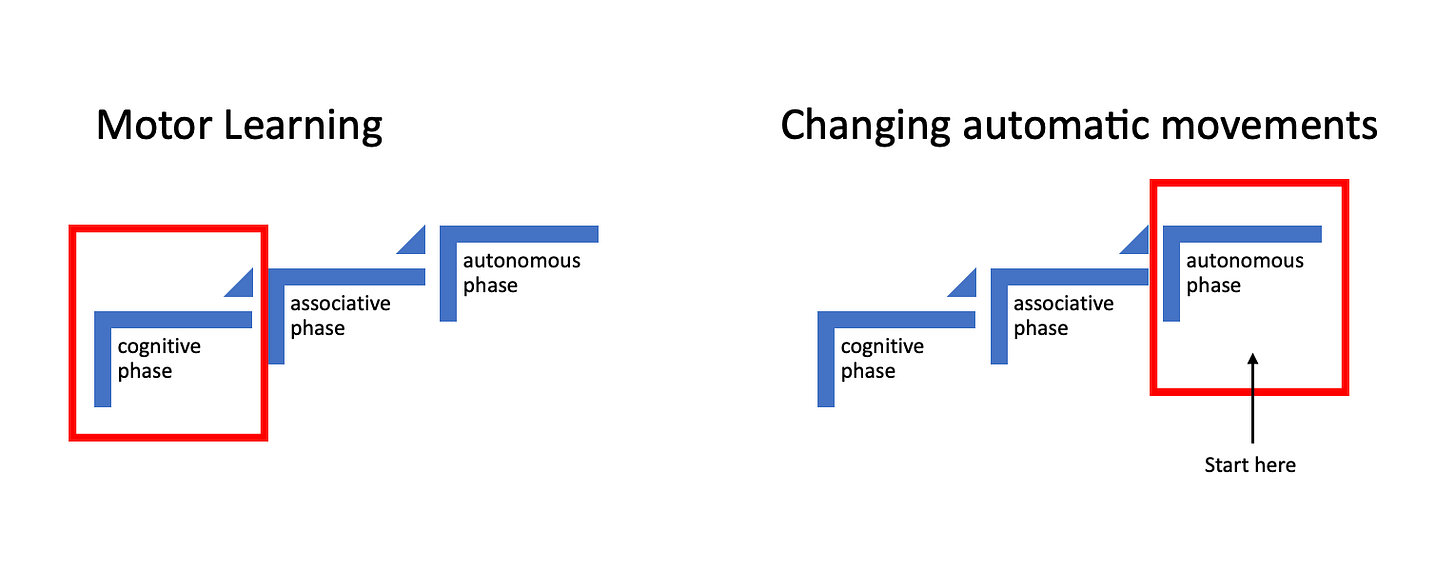

Literature on changing automatic movement patterns is scarce. Part of the problem is that different researchers use different terms, such as relearning, error correction, or adaptation learning.2 That doesn’t mean it isn’t a hard and worthy problem — especially at the very top of the game. The difficulty lies in the fact that your brain has a motor pattern deeply ingrained that has worked against 99.9% of players. Making a change means swimming against the strong neural currents of your motor pattern. Below is a diagram of Fitts and Posner’s (1967) three stage model of learning with the different starting points for a novice versus an expert on a particular skill.3

While technical changes have the goal of enhancing athletic performance, they can often result in an initial performance slump.4 Additionally, even if a player starts performing well with the new technique in practice, it does not always translate as smoothly to the competitive environment. For these reasons, Panzer et al. (2002) suggested that changing an existing skill is perhaps harder than learning a new skill, precisely because the athlete can’t start tabula rasa. It’s like watching a tattoo artist tasked with covering up some god-awful ink: they have to work with what they’ve got.

There are two distinct mechanisms at play when existing motor patterns are already ingrained. Positive transference is when an already acquired motor pattern helps the athlete in a novel situation.5 This is the argument David Epstein makes in his book Range, and is the phenomenon people are referring to when Djokovic credits his childhood skiing experience for his movement on the tennis court, or when people suggest playing soccer is good for your tennis footwork. The existing motor patterns map to the new environment in a way that enhances the athlete’s performance. Contrary to this, negative transference — labeled as interference — is when an existing pattern leads to performance decrements:

“the old, automatized and still dominant movement pattern competes against the new, to-be-acquired movement pattern…This kind of interference can disturb both the acquisition and recall of new memory contents, especially when situations are similar and cues for the old behaviour are active.” (p. 25)

— Baxter et al.,(2004) as cited Sperl & Canal-Bruland (2019)6

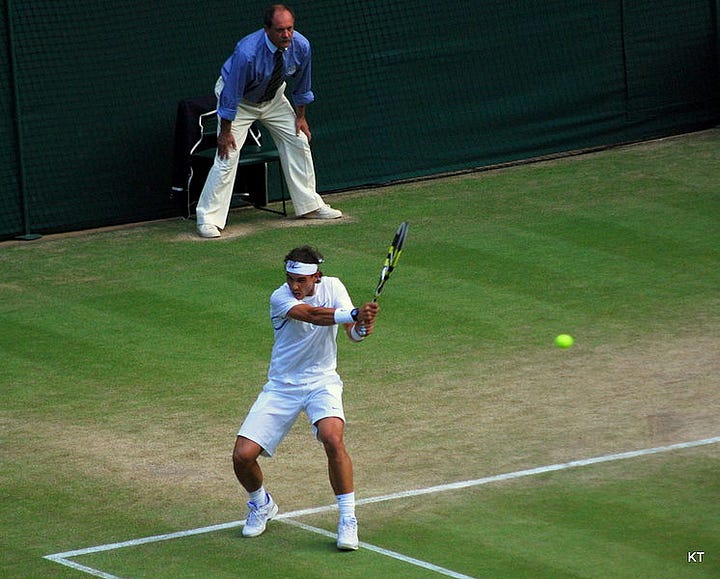

One of the clearest examples of interference I saw repeatedly when coaching in Australia was getting cricket players who bat left-handed but played tennis right-handed (and vice versa). Their batting stroke meant they played their tennis backhand like an inside-out push-slice (read: off-drive, if you are familiar with cricket parlance). The racquet would get steep in the backswing, and then the hands would push the racquet on the Ferris Wheel, rather than the merry-go-round, to use some terminology familiar to readers. You can see how Sachin Tendulkar’s elbows are vertically aligned in his cover-drive follow through, the left elbow high above the right, versus Nadal’s horizontally aligned backhand drive, the left elbow below the right, in the images below.

Photo credits: Tendulkar by Flying Cloud. Nadal by Carine06.

And if you want to see an amazing example of transference, have a look at Nadal’s golf drive. What does that swing remind you of?

There are a number of proposed interventions for changing movement patterns. However, these approaches have been tested in limited cases and contexts. The success of applying them to complex ingrained motor patterns that are inherent to professional tennis remains unclear. Two are summarised below.

Method of Amplification of Error (MAE). By exaggerating the incorrect movement — the principal error — the athlete receives internal feedback. Most error correction strategies involve coaches verbally instructing (external feedback) the athlete what the error is. MAE proposes that amplifying the core mistake triggers an internal search strategy for alternatives and also helps the athlete discriminate what are the incorrect movement patterns.

Old Way New Way. Coaches bring awareness to the athlete of the incorrect movement who are then taught to discriminate between a correct and incorrect pattern. The intervention involves three phases: (1) a preparation phase where the athlete learns to discriminate between the ‘old’ versus the ‘new’ way; (2) a mediation phase involves the athlete describing the old way before then performing the new way. Following this, the athlete then explicitly reflects on similarities and differences between the two patterns, before undergoing the mediation process again on another trial; and (3) the new skill is generalised and applied with repeated practice.

Mindsets

Despite the inherent difficulty of relearning an existing pattern and the lack of a proven method, I believe the very best players carry a mindset that is willing to take risks and embrace change in search of better outcomes.

Sometimes these changes are less obvious in an isolated, technical sense. Perhaps the player has embraced a tactical adjustment to become more aggressive, or more patient, in certain situations, but we do often see players making technical changes in search of better outcomes. Jannik Sinner is the best example from this year: his serve technique was tweaked multiple times in the past 18 months before settling on his current, much improved, motion; he has continually worked in the forehand drop shot off the back of his power hitting; his improved shot tolerance and rally-ball change of direction was evident during the recent indoor swing; and his willingness to come forward was showcased in multiple wins over Medvedev after trailing their H2H 0-6 (now 3-6).

There is a certain courage required when you’re already ensconced high in the rankings. It would be completely understandable if Berrettini didn’t make a change to his backhand, or if Medvedev didn’t work on his volleys (I’m not saying this is the case) because re-doubling their efforts on their strengths would still yield positive, top-10 in the world, multi-million dollar results. There’s a lot to be said for doing what you’re good at once you’re in the money pit, but the very best tend to continually search for improvements.

I came across this short thread from the twitter user ‘Mental Golf Coach’ (@joshlukenichols) that I felt perfectly encapsulated what a clear, process-oriented training program might look like to create meaningful change. I’ve fleshed it out below.

Exaggerate practice swings. “I did the same drill for hours a day, 6 days a week, for over a year, and it probably changed my arm movement just a couple of inches.” You see golfers doing this all the time to get a desired feeling on a swing. There are multiple methods of doing this. I’ve heard of coaches amplifying the movement outside of the sport to get the athlete feeling the desired move without the judgements that come with poorly struck tennis shots. For example, getting the player to throw a baseball and work on the internal rotation of the shoulder, before taking it to the court with the racquet. This is an example of engineering positive transference. Contrary to this, there is also the ‘Method of Amplification of Error’ (MAE) that I mentioned earlier.7 Anyway, here’s Tiger doing some exaggerated swings on a bunker shot:

Tracking stats. Tennis isn’t great at this yet, but getting your hands on some objective data regarding consistency, speed, spin, etc., helps to track your progress and gives clues as to what you need to do better. The stats don’t lie. “What this encouraged was a process mentality, rather than needing results right now. It kept things much less emotional and more logical.” Alongside this I would include the use of video tracking software. High-speed cameras allow modern day players the ability to detect patterns of movement that lead to successful execution. There are similarities in good strokes and there are often similarities in incorrect strokes, and athletes can use video to separate the ‘feel’ versus ‘real’ phenomenon.

"Very little in nature is detectable by unaided human senses. Most of what happens is too fast or too slow, too big or too small, or too remote, or hidden behind opaque barriers, or operates on principles too different from anything that influenced our evolution. But in some cases we can arrange for such phenomena to become perceptible, via scientific instruments.”

— The Beginning of Infinity, by David Deutsch

Practice planning: planning practices ahead of time removes the emotional practice urge (to practice what you didn’t do well that particular day) and helps you practice the right things for long-term improvement. It’s human nature to gravitate toward what we do well; no matter the level it’s uncommon to see people enjoy working on their weaknesses, but setting aside time to seek out better movements/outcomes on a particular shot is necessary if you want to improve.

Post-evaluations. “Journaling and reflecting on stats”. It helps you get clarity on your performance, rather than relying on our shoddy memories. Reflection is considered the key to experiential learning by some researchers. Gilbert and Trudel (2006) quoted something similar on coaching: “ten years of coaching without reflection is simply one year of coaching repeated ten times” (p. 114).8 I think most top players are obsessed with tennis, and this obsession means they reflect a lot on their matches, they watch a lot of other matches, and are genuinely curious about all facets of the game. This curiosity can then bleed into their own game as they pick up on strategies and techniques. Alcaraz said he watched Murray and Federer’s footwork in preparation for his Wimbledon title.

This process-oriented approach reflects similar notions of mindfulness and acceptance protocols that are in vogue with sport psychology (and psychology more broadly). From a piece on competence and confidence and the direction of that relationship:

“Clients begin to accept their hardships and commit to making necessary changes in their behaviour, regardless of what is going on in their lives and how they feel about it.”

— Psychology Today

The difficulty with professional tennis is the length of the season and the constant competition that makes adopting changes a risky proposition; players simply don’t have time to practice without the threat (or obligation) of competition for a few months. Yet, we still see players make changes during the competitive season, and we have seen them payoff: Ruud changed his backhand midway through 2022 on his way to his best season; Sinner tweaked his serve in 2022 and 2023 and his current iteration is paying dividends; Thiem shortened his groundstrokes in 2019 and began dominating the Big-3 on hard courts; Alcaraz adjusted his movement after Roland Garros for the lawns of Wimbledon in a matter of weeks and defeated Djokovic in the forehand battle; Sabalenka fixed her double faults with the help of a biomechanics expert.

To quote the Australian Sports Psychologist, Jonah Oliver:

‘In life and sport we’ve got to focus on bringing people’s competencies out, not searching for this idea that we have to be confident before that can happen. You know, confidence actually follows competence. Do you want a competent team or a confident team?”

As I mentioned earlier, there is a prevalent meme in professional tennis that you need to focus on your strengths and accept your weaknesses as a matter of best course. I think this is true in terms of helping to clarify a player’s identity, or player DNA, on the court: you want Berrettini, Auger-Aliassime, and Rublev attacking with their forehands after the serve; Cressy needs to serve and volley; Dan Evans needs to slice the backhand and be patient. Knowing your style is essential, but I do think there is often a disconnect between a player’s dreams and their actions. Reality cares little for our dreams or our words.

Fates are determined by physics.

To quote a line from the Toronto final analysis between Sinner and de Minaur:

“When you cede technical inches in your strokes that are crucial to generating controllable power, your fate is largely dictated by the opponent.”

As important as it is for players to have a clear identity of how they play on the court, it needs to be malleable enough for them to be able to adapt. That word — adapt — is perhaps the most important word in tennis, as Djokovic reflected on Alcaraz’s game after his Wimbledon loss:

“Roger and Rafa have their own strengths and weaknesses…Carlos is a very complete player. Amazing adapting capabilities that I think are key for longevity and a successful career on all surfaces.”

It’s possible that better players are simply the ones who have a talent for adaptation. It’s also possible that the players who tend to adapt well do so because they have certain psychological traits that predispose them to get ‘caught’ learning. What I mean by that, is that they allow learning to happen because they embrace changes and are willing to try new things, even within the stressful environment of competition. They probably lose matches they could have won trying to incorporate changes.

Very early subscribers may have read a piece I wrote on contextual interference and interleaving: the necessity of variation for effective learning. This theory runs counter, or contradicts, the “high repetition” meme that is also prevalent in sports. “Feed them 50,000 balls in practice and it will be better.”

Maybe.

Or maybe coaches confuse performing with learning. Another quote from the contextual interference piece:

It’s very easy to assume learning has occurred when you watch someone groove a stroke and hit it better and better over the course of a closed drill, but that’s not learning well, that’s performing well. Learning is about retention and transfer.

As Bjork and Bjork (2011) explain when discussing desirable difficulties (emphasis added):

“Conditions of learning that make performance improve rapidly often fail to support long-term retention and transfer, whereas conditions that create challenges and slow the rate of apparent learning often optimise long-term retention and transfer.”910

By now it should be clear that changing technique is hard; more art than science, perhaps. Coaches and players alike may be able to identify what is going wrong, but navigating a clear path toward biomechanical efficiency remains unclear. Still, if you want to be number 1 in this sport I believe it to be a prerequisite. Coaches and their players need to align dreams and actions, and to do that there needs to be a culture of honesty. Jeff Bezos sat down for an interview recently and said as much:

“Truths often don’t want to be heard. Important truths can be uncomfortable, awkward, exhausting, challenging. They can make people defensive, even if that’s not the intent. But any high-performing organization—whether it’s a sports team, a business, a political organization, or activist group—has to have mechanisms and a culture that supports truth telling.”

On top of that, athlete self-awareness and humility is paramount for creating action. From Steve Magness:

“You are what your habits are. This sport is won and lost on what your 85% game is. Whatever that is, is what’s going to show up when it matters.”

— Gavin MacMillan, for On The Line.

The 2024 ATP season kicks off in Brisbane in two weeks.

For an in-depth look at changing automatic movement patterns, you can read part of a chapter by Sperl and Canal-Bruland here from a book titled, Skill Acquisition in Sport. I can email a full PDF on request.

Fitts, P.M., & Posner, M.I. (1967). Human performance.

Panzer, S., Naundorf, F., & Krug, J. (2002). Motorisches lernen: lernen und umlernen einer kraftparametrisierungsaufgabe. Deutsche Zeitschrift Für Sportmedizin, 53(11), 312-316.

Müssgens, D. M., & Ullén, F. (2015). Transfer in Motor Sequence Learning: Effects of Practice Schedule and Sequence Context. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 9, 642. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00642

Baxter, P., Lyndon, H., Dole, S., & Battistutta, D. (2004). Less pain, more gain: rapid skill development using old way new way. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 56(1), 21-50.

Milanese, C., Facci, G., Cesari, P., & Zancanaro, C. (2008). “amplification of error”: a rapidly effective method for motor performance improvement. The Sport Psychologist, 22(2), 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.22.2.164

Gilbert, W., & Trudel, P. (2006) ‘The coach as a reflective practitioner,’ in R. L. Jones (ed.) The sports coach as educator: Re-conceptualising sports coaching. Routledge.

Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In M. A. Gernsbacher, R. W. Pew, L. M. Hough, J. R. Pomerantz (Eds.) & FABBS Foundation, Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (pp. 56–64).

One theory for this is that the variation forces the athlete to “re-load” the memory trace after it is “forgotten” between differing skills. Here’s an excerpt from a paper I wrote on teaching motor skills (emphasis added):

Bjork and Bjork (1992) proposed that the distributive practice schedule that is a hallmark of interleaving forced participants to “re-load” memory traces by allowing them to be “forgotten” to some extent and made a distinction between the storage strength and retrieval strength of skills (Bjork & Bjork, 1992; Yan et al., 2019). Storage strength reflected how engrained a skill was within a wider set of knowledge and skills; a former professional tennis player could easily execute a forehand many years after retirement as the memory trace is deeply embedded in their motor cortex and is not dependent on situational cues or recency. Conversely, retrieval strength related to the present moment accessibility or current motor activation of a skill and was influenced by how recently it had been called upon. Blocked practice improved retrieval strength: the skill was effortlessly recalled because it was never “forgotten” in the first place. The athlete never had to re-load the skill under blocked conditions. The paradox is this: our brains need to repeatedly “forget” a skill so that we are forced to generate the mental effort necessary to recall the skill and increase its storage strength (Bjork & Bjork, 2011; Wright & Kim, 2004).

It’s important to recognise that this research has been conducted with amateur’s of simple motor tasks and that research with complex motor tasks have found weaker relationships for the contextual interference effect. There are also differences in measurement. Some studies measure retention (a time component) and some measure transfer (a context component).

Very interesting! This made me think of second language acquisition which is way more difficult than first language acquisition because you already have a functioning first language pattern. Which can and does interfere with your second language learning. (In the analogy, a second language wouldn’t be something completely new, which I agree in sports is easier, because the function of t he „pattern“ is the same as your first language.)

The bit about MAE is interesting. I think that's why those merry go round forehands don't get trained out, because in training under no pressure they can crunch forehands with huge topspin. And the players train a lot more than they play matches