Contextual Interference

Random practice—play more matches

One of the perks of tennis is the endless variety and creativity the game fosters: forehands, backhands, slice serves, kick serves, volleys, drop shots, smashes, backhand smashes, tweeners, two-handers, one-handers, topspin, slice, angles, lobs, and approach shots. That list is still not exhaustive. Compared to, say, distance running, the game is forever refreshing. Check out this one game from Andy Murray and Michaël Llodra at the 2012 Australian Open.

Despite the endless variety a tennis match can produce, much of modern tennis training is centered around repetitive, closed drills: fifty forehands cross-court, twenty serves down the tee, one-hundred shots through the middle. I’m not saying this is wrong. It’s just an observation. Tennis is as much (if not more) about feeling in control of your own game as it is about taking control away from your opponent, and drills of this sort help foster a feeling of mastery and control within the athlete.1

Last week I wrote about implicit motor learning—you acquire a skill without knowing the nuts and bolts of how said skill is performaned. The theory (and much evidence) suggests that when we know too much about how to do something—when we have explicit knowledge of a skill—we are likely to lean on that explicit knowledge in pressure moments in a desire to perform the skill effectively. Overthinking of this sort hijacks the automatic processes the athlete trained so hard to build. The motor pattern stutters, and you miss the shot. It’s very counterintuitive for us—a species that likes patterns, plans, and a sense of understanding of reality—to ‘let it happen’ and trust the instinctive, but that’s exactly what we need.2 In a similar vein, contextual interference is another counterintuitive learning protocol that fools coaches and learners alike.

What is it?

“Contextual interference involves mixing up your practice structure, either by adding different tasks and/or adding practice variability when learning a skill.”3 A tennis example might be feeding forehands and backhands randomly, as opposed to fifty forehands only. The ‘interference’ refers to the (usually) worse practice performance of the skill during the random practice structure, but a greater ability to retain and perform the skill later on. As Hodges (2012) describes (emphasis added):

“blocked practice facilitated performance during acquisition trials, but that the random group facilitated learning as a result of these practice trials.”4

In a nutshell, blocked practice (i.e., 50 forehands in a row from the same court position) makes you perform better during training. You groove the stroke and find a rhythm. However, when it comes to a match the next day, those who have undertaken random practice (e.g., random groundstrokes/point play) perform better. It’s very easy to assume learning has occurred when you watch someone groove a stroke and hit it better and better over the course of a closed drill, but that’s not learning, that’s performance. Learning is about retention and transfer; making it work in tomorrow’s match. As Bjork and Bjork (2011) explain:

“Conditions of learning that make performance improve rapidly often fail to support long-term retention and transfer, whereas conditions that create challenges and slow the rate of apparent learning often optimise long-term retention and transfer.”5

That quote was from a chapter about desirable difficulties, something we touched on in Death of a forehand - Part II. None of this is ground-breaking in 2022, yet I would wager that most training sessions (in most sports, probably, too) fall into the blocked practice group. Buszard et al. (2017) theorised two drivers of this behaviour:

The immediate improvement in the practice task when done with blocked practice is intepreted as learning, rather than performance.

Blocked practice is familiar to the coach’s own experience of his/her own training as a player.

Professional tennis is an interesting sport with regards to contextual interference. In light of what I just touched on, it seems the ultimate practice is matchplay; it’s random, effortful, and confidence-building. It’s rare a player comes off the court proclaiming that they played very well—it may happen 10% of the time—but for the most part, winning a match is about finding a way through, and often times you will play better in your next round (if not for mean reversion, perhaps contextual interference?). Win the match, and you get a chance to play tomorrow. Lose the match, and you’re on the practice court waiting for next week’s event, and likely practicing in a more blocked fashion than your match-playing competitors.

The nature of the pro tennis tour means that better players (i.e., players who win more often) are perhaps getting the highest dose of best practice by virtue of playing more matches. I tracked the total number of matches played across the 2021 season for the current top 100.6 This is what it looks like:

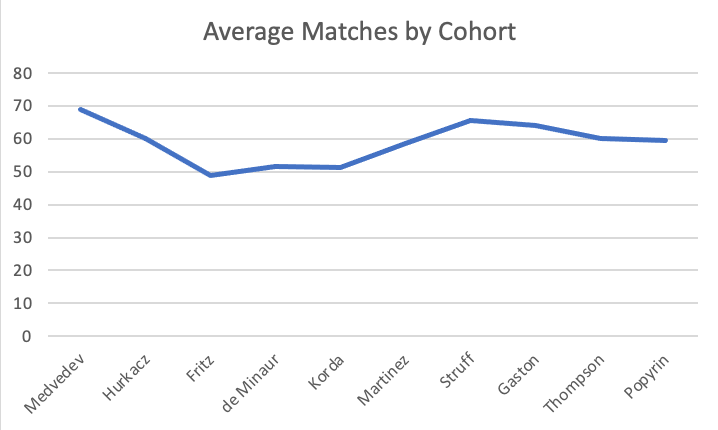

the average number of matches in 2021 for the top 100 was ~57. If we group players by cohort (e.g., 1-10, 11-20…) we get a clearer idea of which cohort played more or less than the tour average:7

I think the main reason for this bimodal pattern is due to ATP rules. Players ranked in the top 10 are barred from entering challenger level events—the tier of tournaments just below ATP—yet they get plenty of matches because they win a lot (hence, top 10). Players ranked 11-50 are also prohibited (however, they can apply for a limited number of wildcards). Players ranked 51 and lower can play as many challenger events as they like. What this means, is that players ranked 11-49 averaged around 16 fewer matches in 2021 than the top-10, and 7 fewer matches than 51-100 ranked players. I don’t know if that makes a huge difference or not, or if that effect holds every year, but it’s interesting to consider that an ATP rule reduces matchplay once a player breaks into the top-50.

There are very few sports I can think of that lead to such disparities in invaluable game-time experience. Most sports are fixtures-based, where each week each team/player plays an equal amount to their competitors. One other sport I can think of is golf, in terms of making the cut.

The video below provides a backstory to Aslan Karatsev’s meteoric rise at the 2021 Australian Open. If you don’t have time to watch it, the tl;dr is this: during the Covid-19 pandemic, and just prior to the 2021 Australian Open, Karatsev played a heap of matches while everyone else was basically sidelined. Did that contribute to his semi-final run at the Australian Open? Probably. Was that the only reason? Absolutely not.

It’s impossible to tease apart why winning matches is good for a player; is it mostly confidence? Does it just signal fitness and motivation? Is there some contextual interference benefit? A bit of luck? It’s likely an amalgam of all these factors and some others.

Nelson Mandela has a famous quote: “I never lose. Either I win or I learn.” In light of the ATP’s top players and contextual interference, it may be more a case of “I win, I get to learn.”

As mentioned last week regarding errorless protocols, easy repetitive drills seem to have their perks too.

Assuming sound technique in whatever domain you are in.

https://sportscienceinsider.com/contextual-interference-effect/

Hodges, Williams, A. M., & ProQuest. (2012). Skill acquisition in sport research, theory and practice (2nd ed.). Routledge

Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In M. A. Gernsbacher, R. W. Pew, L. M. Hough, J. R. Pomerantz (Eds.) & FABBS Foundation, Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (pp. 56–64). Worth Publishers.

Includes ATP 250, 500, 1000, Challengers, Futures, Davis Cup, Olympics, NextGen finals, and Grand Slam matches. Does not include exhibitions or league matches.

Minimum 30 matches played. Nadal (#4), Federer (#27), Thiem (#51), Goffin (#68),Johnson (#93), and Pella (#100) were excluded.