Alcaraz vs de Minaur: Rotterdam Final

heavyweight forehands — north-south movement — defensive slice — serves

Carlos Alcaraz defeated Alex de Minaur 6/4 3/6 6/2 in the final of the ABN AMRO Rotterdam 500 on Sunday to clinch his first ever indoor title. It was the Spaniard’s sixth ATP 500 title and seventeenth career title (17-5 record in finals).

“I'll be a really good player on indoor courts, I'm sure about it.”

— Alcaraz in 2024

While I believe Alcaraz will be a really good player on indoor hard courts when all is said and done, the reality is that Rotterdam has been one of the slower indoor tournaments in recent years.1 The commentators mentioned as much in the warm-up:

“It seems as if the conditions really suit him, going for his first indoor title, but for an indoor hard court these are relatively slow, quite grippy, you know, we’ve seen a lot of kick serves and heavy topspin on the forehand really working, time to use the drop shot, so he [Alcaraz] looks to really be enjoying the conditions.”

— Tennis TV

In the opening minutes Alcaraz showcased how explosive he is when things slow down, courtesy of a mistimed return.

He’d blasted more than 30 winners off that wing in his semifinal win over Hurkacz, and it’s the shot that often steers the fate of his matches.

A comparison of de Minaur’s flatter and eastern-gripped forehand with Alcaraz’s more semi-western and spin-oriented one showcases why the Spaniard has more of a heavyweight shot compared to his Australian opponent (a distinction that I also touched on with respect to Sinner’s versus de Minaur’s backhands in the 2023 Toronto final). From the slot position the Spaniard has got a longer path to swing out toward the ball, from a lower position relative to the ball, and with a more closed racquet face. More spin and more speed.

These differences are what dictate much of the speed and spin data of players:

Players like de Minaur (you could include Mannarino, Medvedev, and McDonald, who are other notable players in the bottom left of the chart) benefit from livelier balls and faster courts where they can almost ‘touch’ the ball and be aggressive, using their timing to create ball speed and aggression. Given the repeated criticism since Covid of balls becoming softer / fluffier / slower, swinging in-to-out with speed seems to confer an advantage in the current era of big hitters.

Despite the swing limitations, de Minaur has tried to beef up his body and his game, especially on serve and with the forehand, and the results have come accordingly in the last 12 months.

But Alcaraz’s ground game is in a different weight class, and he was the aggressor in the opening set, rushing de Minaur for errors to obtain the early break, and then using his north-south movement to conjure shots like this:

But de Minaur would break back soon for 4-4, using his court speed and flat middle consistency to extract errors from the Spaniard, who tends to produce them in bunches. The Australian puts in more balls than nearly anyone, and has the wheels to back them up:

“de Minaur put 68 per cent of his first-serve returns in the court this season [2024], which is six percentage points higher than the Tour average of 62 per cent. De Minaur put an impressive 91 per cent of second-serve returns in the court, nine percentage points higher than the Tour average of 82 per cent.”

As you might expect between the tour’s two premier returners, Alcaraz would answer right away, breaking at 4-4 off the back of a weak approach from the Aussie:

Alcaraz took the first set 6-4, but de Minaur got the perfect start in the second, breaking out to a 3-0 lead off the back of some loose Alcaraz backhands, and some exceptional ones of his own:

The serve and forehand improvements were also paying dividends:

But for all of the Demon’s improvements in his aggression, he still isn’t a big hitter, and Alcaraz’s ability to flip points was given numerous chances, like this gem of a two-shot pass at 30-30:

de Minaur would save that break point with another big serve-plus-one forehand, and would go on to hold courtesy of two more big first serves (the last of which was 211 km/h).

Serving for the set at 5-3, Alcaraz dropped back on second serves and played one of his trademark North-South return points:

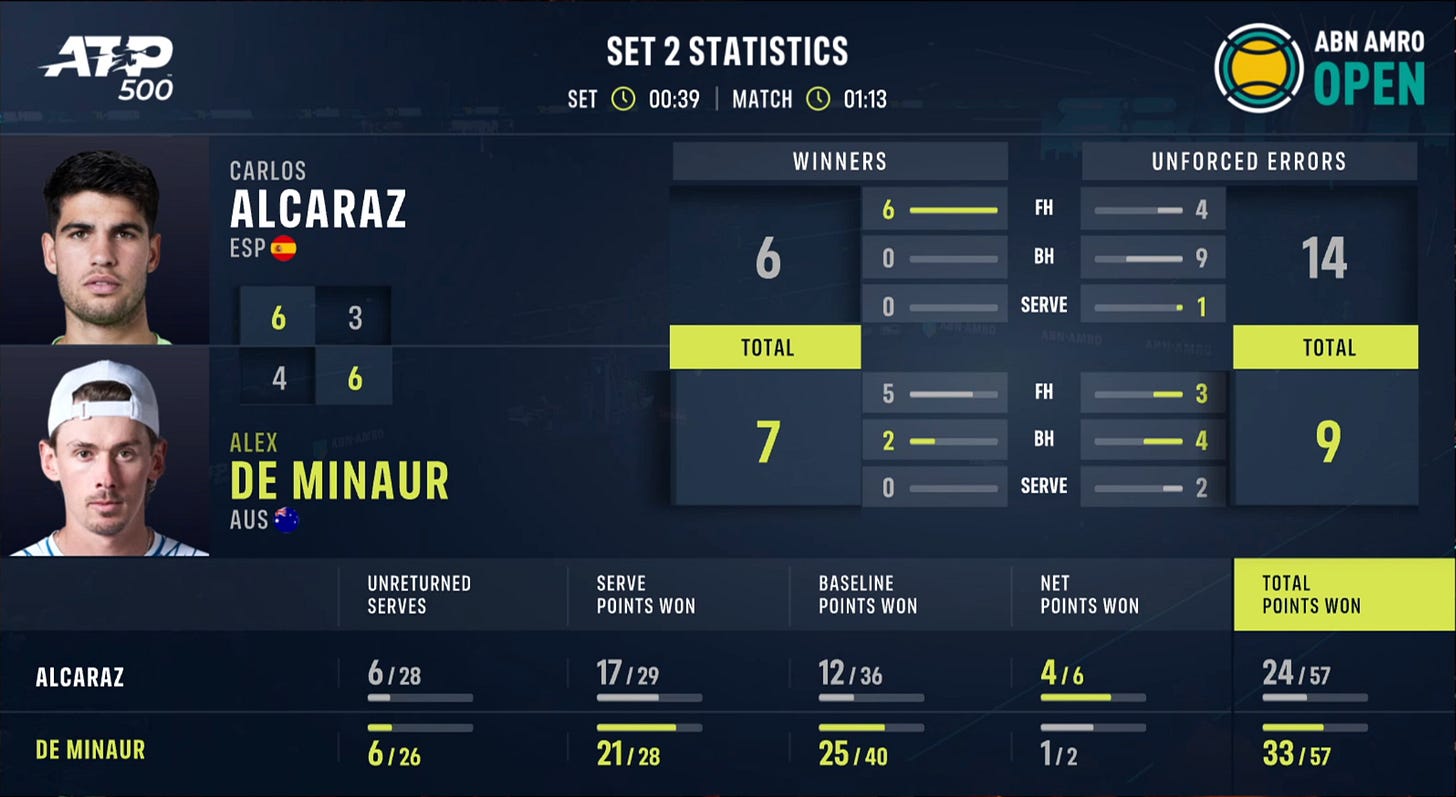

Despite those impressive backhands, it was the shot that let Alcaraz down in the second set, spraying nine unforced errors from that wing for no winners (although that stat fails to account for how the above point was won largely with the backhand, not the final rudimentary volley). De Minaur would take it 6/3:

While the topspin backhand may have gone walkabout, the defensive slice backhand — a trademark of the Spaniard — made its appearance in the third set, feathering this below the net with remarkable feel from behind the TV scoreboard. De Minaur does admirably to run through his split step and take this volley closer to the net, but he played it a little too hard; it’s tough to take speed out of the ball while you’re sprinting forwards. But really, this point is over as soon as Carlos hit the slice well enough to dip it below the net and start his recovery forward. From there, it takes a phenomenal shot to out manoeuvre him.

And it’s not only the passing shot aspect that he possesses. As he did against Shelton in last year’s Laver Cup match, Alcaraz has gifted feel on the defensive slice lob as well, seen here escaping with a win from this:

I really can’t emphasise enough just how freakish this ability is for a young Spanish two-hander raised on Murcian clay. Have we seen anyone recently with comparable feel on their slice? Sure, *Federer and Evans join the chat*, but those guys grew up slicing and defending and scrapping from that wing from young ages; their slices came stock along with their single-handers. Alcaraz has this shot perfected to such a degree despite it being an auxiliary to his two-handed backhand wing. In this regard he’s tennis’ version of a polymath, or Renaissance man, displaying an almost limitless skillset to an extremely high degree.

By comparison, this was de Minaur’s only attempt I could remember:

A few points later Alcaraz held for 2-2, this time hitting a forehand defensive slice off a great counter backhand from de Minaur:

Alcaraz wouldn’t lose another game, as the Aussie’s level fell away, perhaps due to the illness he had been battling all week as well.

A look at the rap sheet:

While both men bled plenty of errors, I think this is more reflective of their court speed and ability to get balls back, as well as both men’s intent in this match to hold the baseline and pressure the other. It was close-quartered, frenetic, middleweight tennis. Still, the Alcaraz backhand did genuinely get loose at times in this match, and while such a compact swing may prove beneficial to his overall strategy of being ultra-offensive (he certainly looked relentless and Agassi-esque at times), it remains to be seen if it can stay consistent enough against the very best.

On another note, it’s still fascinating to me how the very best players — the ones already winning all the slams — seem to be the ones most open to change.

Sinner was testing blacked-out Head frames in October last year, after one of the greatest seasons of all time.

Alcaraz added weight to his frame, changed his backhand, and changed his serve technique after winning the Channel Slam last year.

Speaking of serve technique, despite de Minaur’s speed improvements, he is hitting against a technical ceiling he cannot overcome unless he changes it. So far he’s found improvements in beefing up the body, but he’s leaving plenty of technical muscle on the table. Here’s a comparison between the two (this video was taken in 2024, so this is Alcaraz’s old motion).

These two screenshots were taken at the moment the leg drive was initiated, which you could say is the start of the serve swing in earnest (ground reaction forces start the swing). First of all, look at the different orientations of their bodies. Alcaraz is more turned away from the court with his hips, torso, and shoulders, meaning he can uncoil more when he drives his legs and right hip up and around. His leg drive is also much more balanced between the legs, whereas de Minaur is mainly using his left leg (an important driver of power in the serve is getting the right hip engaged, and being able to push off the back leg can help facilitate this). Then we can see the different hitting arm and racquet structures. Alcaraz’s shoulder is far more internally rotated, so he has more space to build speed as he externally rotates it, which helps create that stretch-shortening cycle as he internally rotates it into impact once more.

Here’s an excerpt from Technique Development in Tennis Stroke Production (emphasis added):

“The shoulder is the funnel for the transfer of energy from the trunk to the racket arm… The pause in changing racket direction from backswing to forward swing should be small to optimise the return of elastic energy to the concentric muscle contraction responsible for this forward motion.”

To make that pause smaller, you want more speed heading into the racquet change of direction.

The win puts Carlos within Masters striking distance of Zverev, and de Minaur’s efforts are rewarded with a return to his career high #6.

There are three 250s this week in Metz (indoor hard), Delray beach (outdoor hard), and Buenos Aires (outdoor clay) to kick off the Golden Swing.

I’ll be back with a recap next week. See you in the comments. HC.

Per the Tennis Abstract site: “uses ace rate — adjusted for the servers and returners in each match — to rate each tournament by surface speed. Thus, the number indirectly accounts for everything that influenced play: temperature, humidity, wind, balls, and of course the physical surface. Ratings greater than 1 are faster than average. For example, a rating of 1.25 indicates that the players hit 25% more aces than they would have on a tour-average surface.” Data from the last four years, with 2024 as the most recent: 1.24, 0.96, 0.99, 0.94.

I watched this Mark Kovacs video a couple of weeks ago on serving. You're right about the back hip. The biggest determinant in serve speed is how fast you can get your back hip to rise vertically https://youtu.be/krKYy4eqgdQ?si=Fmx_vulit2PdmnGC&t=345

I've been tweaking my 1st serve, and I've noticed that I have put too much of my weight on my front leg in a platform stance. That's something you discussed with De Minaur. That has caused me a hip flexor issue. I am now practicing jumping up into the ball with both legs equally.

You mentioned "A comparison of de Minaur’s flatter and eastern-gripped forehand with Alcaraz’s more semi-western and spin-oriented one showcases why the Spaniard has more of a heavyweight shot compared to his Australian opponent (a distinction that I also touched on with respect to Sinner’s versus de Minaur’s backhands in the 2023 Toronto final). From the slot position the Spaniard has got a longer path to swing out toward the ball, from a lower position relative to the ball, and with a more closed racquet face. More spin and more speed." When you explain the de Minaur eastern grip FH technique in this instance being inferior to the Alcaraz semi-western FH technique, is this a generalized carry over for every eastern FH compared to a semi-western FH or just those two in particular. I say this because in the death of the forehand Del Potro and FRAUDerer were amongst the top tier FH models you mentioned yet they are eastern and had plenty access to spin so I'm confused if de Minaur's issue is partly due to his eastern grip for today's FH metagame or the actual "elbow high" take back, "back-to-front" swing or are both factors. Is the eastern grip a grip to be wary of using today? (I myself have an eastern grip with a trigger finger hold).

You also mentioned "That slice from Alcaraz is really quite effective against a flat and underpowered hitter. It’s difficult for de Minaur to attack it with his flatter strokes compared to someone like a Sinner (or Alcaraz) who can wail on that kind of ball given they produce a lot more spin and racquet speed." Does that slice bother the likes of Del Potro who despite his ability to clock the ball insanely hard he is on the flatter side albeit he isn't underpowered, FRAUDerer also had the first strike abilities and has had spin rates clocked at levels second to Nadal at one point despite his eastern grip? does the slice bother those two despite them having the ideal "global maximum" eastern FH?

You also mentioned "Alcaraz gets farther beneath the ball and with his strings still closed compared to de Minaur, who’s racquet face is already “on edge” or perpendicular to the court. These differences are what dictate much of the spin and speed data." So for example here correct me if I'm wrong but in the case of having a closed racquet face as you swing with a more classic grip like eastern is nothing a conscious effort to just tip your racquet face "more" closed as you swing can't fix? You wouldn't propose that an eastern grip player is technically capped as a result of that grip naturally guiding through the ball instead of the more natural extreme upcut of the semi-western on the ball today's FH metagame seems insistent on? Think an eastern grip FH can top the charts today/or future on a heaviness/speed/spin chart or is there a glaring limitation you notice with the eastern grip FH.

P.S: Congrats on being a dad. Didn't realise you were till I listened to the podcast weeks ago.