Jannik Sinner defeated Daniil Medvedev 7/6 4/6 6/3 in the final of the Vienna ATP 500 on Sunday to clinch his fourth title for the season (10th overall, fifth indoors) and improve his H2H against the Russian to 2-6.

After their Beijing match I wrote:

Sinner has been one of the youngsters who has continually showcased a willingness to change and tinker—technically and tactically—in search of improvements right before our eyes.

In Beijing Sinner showcased improved netplay, patience with his forehand, and an overall level of athleticism and fitness that has earned him the world number 4 ranking; a reflection of his consistency across the year. This from Twitter user Vansh.

While Sinner’s performances in Slams in 2023 haven’t been exceptional (only at Wimbledon, where he lost to Djokovic in the semifinals, did he reach the quarterfinals or better) the young Italian has been slowly building a game that is looking more and more ready to breakthrough with a final at the majors in 2024.

The serve numbers have improved since he changed his motion and today it was the key to salvaging the first set tiebreak from 1-4 down. The drop shot is a tool he is using more often. The serve-and-volley—a feature of his win against Medvedev in Beijing—is also getting plenty of reps in match-play.

What I liked from Sinner today was his willingness, and perhaps more importantly, ability, to spread the court with both his groundstrokes, especially his backhand down the line. In the third point of the match Sinner displayed fantastic shot selection in the 19-ball rally, absorbing Medvedev’s attacks with crosscourt defense, until finally an opening presented itself, and he took his backhand line with margin.

Robbie Koenig after this shot: “Such an important shot in the modern game, that backhand down the line, because so many players enjoy playing out of their backhand corner—dominating from that area of the court. This one, exposes them.”

A look at Sinner’s backhand shot map from their previous final in Beijing and from today in Vienna shows that Sinner made a concerted effort to take his backhand down the line more today:

Sinner has often been compared to Djokovic in terms of game style, a comparison I have rejected because at their core I felt Sinner was an offensive baseliner and Djokovic a counterpuncher.

But Sinner has shown in his last two matches against Medvedev that he is willing to eschew pace and speed for control and direction in a Djokovic-esque manner.

As Koenig mentioned in the above quote, many players like to play out of their backhand corner—especially with their forehand—but I think most players prefer to, or feel more comfortable, defending out of their backhand corner also; the running forehand is the loosest shot on the court in most matches.

In recent slam performances, I’ve highlighted how Djokovic has exposed many youngsters early in matches with his off-backhand and line backhand (vs Alcaraz in Paris, and Tommy Paul and Stefanos Tsitsipas in Australia) against forehand-hungry players. Here’s an example:

I felt Sinner displayed an ability to change direction today with more patience and margin—in terms of his shot as well as his position—than I can remember him using. Here’s an example:

The perils of hitting down the line are clear to all who play: the net is higher at the singles lines, and the shot is shorter in length compared to going crosscourt (from corner to corner the crosscourt shot is four-and-half feet longer!). These two factors alone mean the risk of missing—either in the net or long, is higher.

Furthermore, timing the ball so you don’t miss wide is also harder because you have to change the angle of the incoming ball. In my opinion, the best exponents of change-of-direction backhands are those players who hit it with the locked wrist follow-through, or an absence of top-hand roll: Djokovic, Korda, and Agassi come to mind. As I touched on with Hurkacz in Shanghai, the racquet tip often finishes pointing left with the right elbow very high:

Sinner’s backhand, while exceptional at creating speed and spin due to his enlarged takeback and closed strings (Nadal is similar) has a strong left-hand finish. It means timing a change-of-direction ball is a little harder because the strings don’t remain “on-target” for as long as the locked-wrist backhand, although you typically can get more topspin. As always, tennis is a game of tradeoffs.

For a crude demonstration from my living room in socks, looking to nail a backhand down the line (or the broomstick, in this case). Here is the swing path of a locked-wrist “push” backhand like Korda et al.:

And a Sinner-esque roll backhand:

When we track the swing paths of each, you can see how the locked-wrist backhand–while not generating as much spin—enables a player more margin for error in timing the ball as the strings stay “on-target” for longer:

Of course, the roll backhand does enable a player better crosscourt angles, and Gill Gross pointed out several times in his breakdown how well Sinner did get Medvedev outside the singles lines with sharper angles than usual. That was something I didn’t pick up on in my viewing—I was too focused and impressed with his down-the-line balls from both wings—but is certainly a strength of the Sinner game because it suits his roll-backhand swing.

But back to the line ball. Beyond making your shot, there is also a risk that if you don’t hit it well and your opponent gets there easily, you are now well out of position because where the true “middle” of the court is has shifted.

This video from Online Tennis Instruction does a good job outlining the geometry and risk of line balls

Hence why I have suggested the importance of the off-backhand as a real gem of a shot to have in your bag.

You hit it from closer to the middle, so now the net clearance required is lower, you aren’t out of position if you drag it middle, and hitting it well means it continues to run away from your opponent.

When you consider that Medvedev’s MO is to play deep middle—especially to a player’s backhand—it is a shot that can have a huge impact on your ability to undo the Russian’s defenses.

When I watched Sinner today, I felt he was very disciplined with when and where he changed direction on his backhand side. Sinner did a great job changing from position B—closer to the middle—and staying cross-court from position A unless he was really set in position (and by that, I mean he usually had time to get on the front foot and/or play it further inside the baseline). I also felt Sinner was disciplined with his change-of-direction off the forehand wing.

With that being said, and as well as Sinner played, you can see how difficult this matchup is for the Italian because it requires him to play outside his comfort zone. He needs to use more variation—slices, drop shots, higher balls, and angles—if he wants to make an easier go of defeating Medvedev. Cahill was heard saying as much when Sinner was down a break in the second set. There were instances where he showed this:

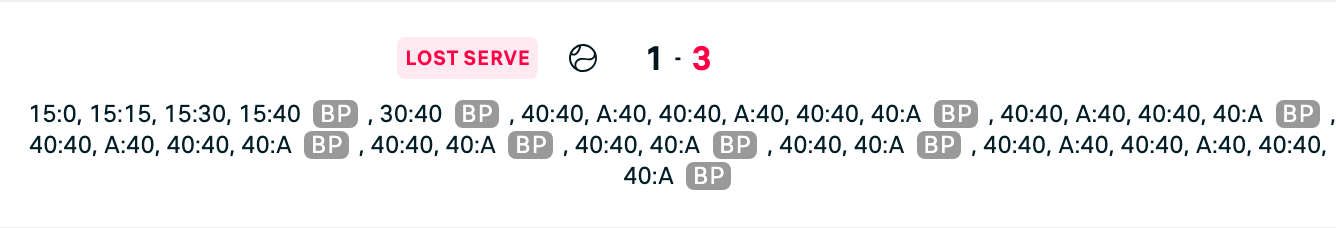

But overall this was just a truly physical war of attrition between two baseliners. Sinner didn’t come forward as much as he had in Beijing, as Medvedev had punished him with brilliant returns early in the encounter. This made the match more of a slog, and Sinner held strong. The 2-1 game in the third set was 20 minutes and an unbelievable test of each man’s physical and mental strength.

Perhaps Sinner didn’t look to use as much variation or attack because he has more confidence in his movement and fitness now. The match overall was a quality baseline battle: lots of punishing exchanges that pushed each man to the limits physically and skill-wise. That Sinner came out on top in that test bodes well considering his fragility has often been a question mark. Sunday’s final was another data point suggesting he is figuring out that aspect.

In other news, Felix Auger-Aliassime returned to the winner’s circle with his defense of Basel, taking out red-hot Hubert Hurkacz in two busters.

The Paris Masters is underway already and I’ll be back with a final analysis next week.

See you in the comments.

Great piece H! It's been a treat to see Sinner evolve his game and begin to turn the tables on a guy who's had his number for some time...in b2b finals no less!

A couple questions I'm curious to get your thoughts:

1) Can you elaborate on why "the running forehand is the loosest shot on the court in most matches"?

2) For the backhand technique, is it possible to develop both to have the option of using the locked-wrist backhand or the roll backhand? Or are they so technically different that it simply makes sense to commit to one style for the sake of muscle memory, stroke consistency etc? Based on what you wrote, there are distinct advantages where it might just be ideal to have both options at one's disposal.

One of the things I noticed after Beijing was that, compared to Rotterdam and Miami, Sinner went for way more Deuce-wide first serves. It worked a lot in Beijing. This time, Medvedev had done his homework and burnt Sinner with the CCFH return multiple times in the first set. Sinner's win rate on Deuce-wide first serves went down from 78% in Beijing to 61% in Vienna.

The fact that he still managed to win, is mighty impressive. Shows that he is adding more and more tangibles and intangibles to his game.