Djokovic def. Shelton 6/3 6/2 7/6

Before this match I tweeted my thoughts on this first semifinal:

“Hot and humid day session with the home crowd. Best possible conditions for Shelton if he’s to have a chance. Will need the first set to keep the crowd involved. Djokovic is too good of a front runner. I think Novak will try to keep Ben moving: he’s [Shelton] still a little heavy and ND is so good at changing directions and keeping players from feeling set on their shots. Shelton needs to find his forehand early and go hard with it. No point screwing around.”

This was another masterclass from the Serb, who dismantled Shelton’s power game with his ability to blunt the big serve and then turn the screws from the back. One of the talking points of the tournament has been Shelton’s serve power (twice he sent down 149mph thunderbolts this fortnight. Today he thundered down a 144mph second serve). Truly huge serving has always drawn an excited gasp from the crowd the same way long drivers do for golf, but as they say in that maddening game: “Drive for show, putt for dough”.

The same notion holds for tennis, although it isn’t exactly clear what tennis’ putting equivalent is. Perhaps it can simply be one’s ability to redirect groundstrokes at 70mph. This isn’t particularly sexy or exciting to casual observers, in fact it sounds downright benign, but much like compound interest, it pays off handsomely over time, and it didn’t take long for the cracks to appear in Shelton’s game. He was broken in the sixth game, committing four unforced errors that were all the result of pressing too hard and too early against elite defense. In contrast, Djokovic was using his innocuous rally pace ball, the below example off the backhand wing in that silent killer fashion: down the line, catching opponents leaning on the crosscourt anticipation. It’s rarely a winner, but nearly always earns a short ball or forced error. No one else extracts so many errors from rally-ball pace placed in aggressive areas. No one.

So while the power was squarely on Shelton’s racquet, the ability to dictate the terms of the match largely rested on Djokovic’s all-absorbing strings:

There is still a lot of upside for Shelton. First of all (and I don’t have any map data on this yet) it seemed to me that Shelton’s serve accuracy isn’t great yet. He doesn’t quite stretch the court as well as he could—especially as a lefty. When he did, he looked great:

Marrying that huge power with sharp and accurate angled serves would make him that much harder to break.

Secondly, he lacks great intangibles—slices, block returns, volleys, drop shots—those gritty cat-and-mouse elements when you’re flying in the forecourt by dead reckoning and require slick feet and slicker hands. But Shelton is a great athlete, I like his technique, and we can expect him to add these elements and refine his physique as he gets accustomed to life on tour and grows with experience. It is his first year on tour, after all.

In the end, while Djokovic let a routine third set become a little more complicated, Shelton was just too raw to present as a genuine threat to the 23-time slam champion, and his ability to be consistent while moving was tested beyond his means. As predicted, Djokovic made his younger foe do most of the legwork, and came out with a more favourable winner:unforcer error ratio:

Djokovic: “The Grand Slams are the ones that motivate me the most to play my best tennis, perform my best tennis. I knew prior to the quarter-finals that I would play an American player and that is never easy. To control the nerves and be composed in the moments that matter. Today things were going really smoothly for me and then he broke back and it was anyones game at the end of the third set. This is the kind of atmosphere we all like to play in, so I am really, really pleased with this win today."

Medvedev def. Alcaraz 7/6 6/1 3/6 6/3

The opening games of this match featured themes we have covered before: Alcaraz’s forehand susceptibility and tendency to bleed errors out wide; and his ability to serve and volley on Medvedev’s deep return position. Tied at 3 games a piece in the first set, all six of Alcaraz’s unforced errors had been committed from the forehand wing, and he’d let slip several chances on Medvedev’s serve by mistiming a handful of second serve returns. At 4-4 in the first set, Alcaraz had ventured forward 15 times already and won all 15 points, with the vast majority of these volleys played short, even when faced with unfavourable positions, in a bid to get the Russian taking the longest route possible to the ball.

Although their previous two encounters, at Indian Wells and Wimbledon, had been blowouts in favour of the Spaniard, Medvedev has overall been playing well in 2023, in part attributed to a string change that allowed him to get more spin on his forehand. In my US Open preview I wrote:

“I think Medvedev’s losses recently haven’t been bad; he’s run into form players in de Minaur and Zverev and he’s played some big points poorly. Overall he’s still a menace at the US Open…”

Tonight, he showcased what a hardcourt menace he is when he gels his brick-walled groundstrokes so relentlessly. He reminded most of us—me included—that you should never count out a US Open champion with a great record against world number one players.

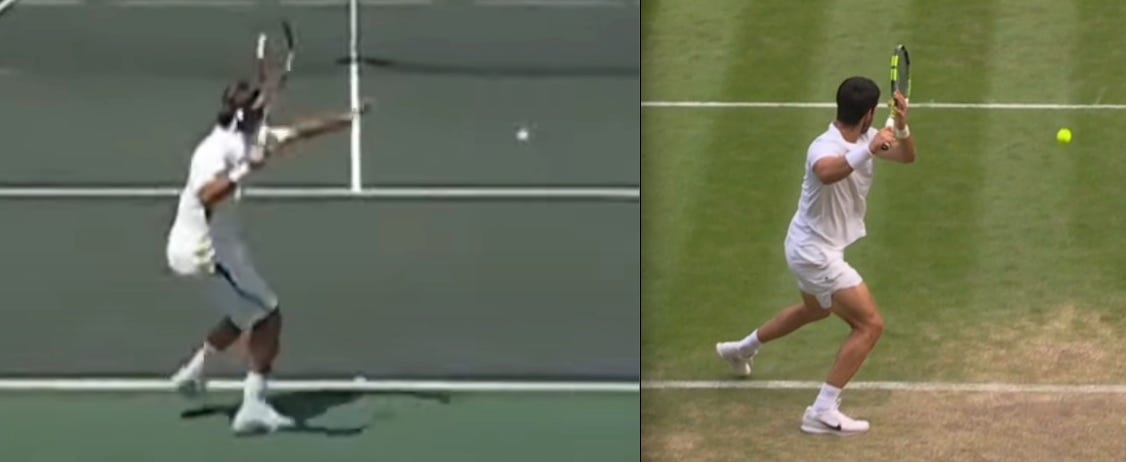

Despite lacking firepower—a weakness that probably cost him that famous Australian Open final against Nadal—the Russian has exceptional racquet face control, courtesy of minimal wrist action and very little lag. His backhand down the line—a feature of Djokovic’s game also, with both men having takebacks that start from inside the line of the ball—was on fire this evening, catching Alcaraz off guard over and over again as the Spaniard looked for ad-court forehands:

Robbie Koenig: “That backhand down the line has been kryptonite for Alcaraz this evening.”

Medvedev: “I said I needed to play eleven out of ten, and I played twelve out of ten.”

Ultimately, I felt Alcaraz was a little too aggressive and impatient for the first few sets here. His Wimbledon victory was so great because he played a contained brand of tennis for much of the encounter. When he finds the balance between patience and tornado offense he is a different player. Yet, at just 20 years old it’s natural that such harmony is yet to be achieved consistently, especially given how exceptionally broad his repertoire already is. Still, this match should serve as a reminder that you can expect to be punished if you lack discipline this deep in slams. What turned the match around in the third was in part a willingness to take some heat off and build the points. The average rally length jumped from around 3.5 shots to 4.5 shots during that momentum swing.

Koenig: “He went into Medvedev beastmode. Tactical masterclass today, the way he used his backhand down the line and forehand crosscourt to breakdown Alcaraz’s forehand.”

“He [Alcaraz] couldn’t bring his A-game and he wasn’t allowed to bring his A-game.”

The rap sheet shows just how tidy Daniil was, and how erratic Alcaraz was:

In a repeat of the 2021 US Open Final, Medvedev will take on Djokovic.

Medvedev: "The challenge is to play a guy who won 23 Grand Slams and I have only one. When I beat him here, I managed to play better than myself and I need to do it again. There is no other way."

Always cagey, what has often separated these two are two key areas:

First serve percentage

Forecourt ability: slice/drop shots/volleys etc.

Because both are natural counterpunchers, the rallies tend to extend when the free points on serve dry up. As both defend so well with their stock groundstroke games, their ability to execute short slices, drop shots, and sneak volleys has often played a crucial role in unsettling the other. Djokovic has come out on top recently in such matches, winning four of the last five. However, with Medvedev’s newfound confidence in his forehand and improved ability to dictate with that wing, we might see the Russian surprise us once again.

Let’s hope both men bring their best.

I think Daniil's FH deserves some more love – that shot felt equally instrumental to breaking down Carlos' FH in the same way he so expertly used his BH dtl. He was hitting it so flat and striking through it so well and with so much precision tonight that he was finally able to trouble Carlos' FH wing in a way that felt overdue. Not only was he doing a good job of rushing that wing despite not having the strongest weapons (in terms of straight power), he was also stifling that wing and frustrating Carlos in a way that he had seemingly overcome after the Novak final, and to some extent the little adjustments vs Zverev in the QF.

I think there's a weak spot that low, flat & particularly short balls can access against his FH that can keep him tied down. I mentioned it in my piece on the WIM final and tweeted about it here (https://twitter.com/AnettKord/status/1700346229887017446), if you're interested, because I've seen Novak & Zverev use it when they've beaten him (dating back to his 1st meeting w/Novak).

My view of it is that it's a trade that dangles the carrot without moving the ball close enough into Carlos' body that he can successfully unload on it, which means he pulls up on/away from it as he's very square-on, leaving his right leg with nowhere to go. I'm guessing that if he had a more Rune-esque FH technique, he'd more easily let the ball come into him and move through it to redirect and use pace with relative ease, but because he tends to explode through the shot instead, he ends up redirecting with a lot of unintended air in the ball. That made for a lot of soft redirects tonight.

When it has happened in the past, it's then limited him to playing almost exclusively cross court (Zverev @ RG nailed this imo with very short depth, mixed in with aggressive rushing), and that's how he then becomes frustrated by the lack of options. It's too far in front of him to power through the cross court angle, so then he either loses patience (= netted balls trying to power it dtl without a good base/overcooked cross court shots) or he uses the short angle, which players like Daniil, Novak, Zverev, etc. can easily retrieve. And, when they do get it back, it's usually with interest (Novak countered from out of position that way this year @ RG, of course, and there's a good example of Daniil doing so in the thread of mine I linked) to ensure that his redirect into the vacant space is retrievable. It's also a hugely beneficial strategy because it allows Carlos' opponent to stay close to the baseline, which takes away the dropshot.

Hopefully what I've said makes actual sense and maybe you can correct me on it or the finer details of why that's the result of it, but it's definitely a stand-out pattern I've noticed. Obviously, the aspect of rushing the FH, getting it on the run, etc. are all greater points of focus, but I think it compounds it well. As to why he unravelled without solution tonight, I think the H2H factors in (as well as Daniil's insane level), because he'd been made to learn by defeats to Novak, Zverev, etc, so this was a whole new challenge.

(just realised how excruciatingly long this message is, sorry about that, hope it's ok.)

Stellar analysis as usual. Despite having a technically sound forehand, what do you think hinders Medvedev from getting more pop on it, as opposed to players with “livelier” arms or “easy” power (Alcaraz, Sinner, Shapovalov)? Do you think it’s simply his overall game plan that encourages him to take off pace? Or are there some technical flaws that are harder to notice?