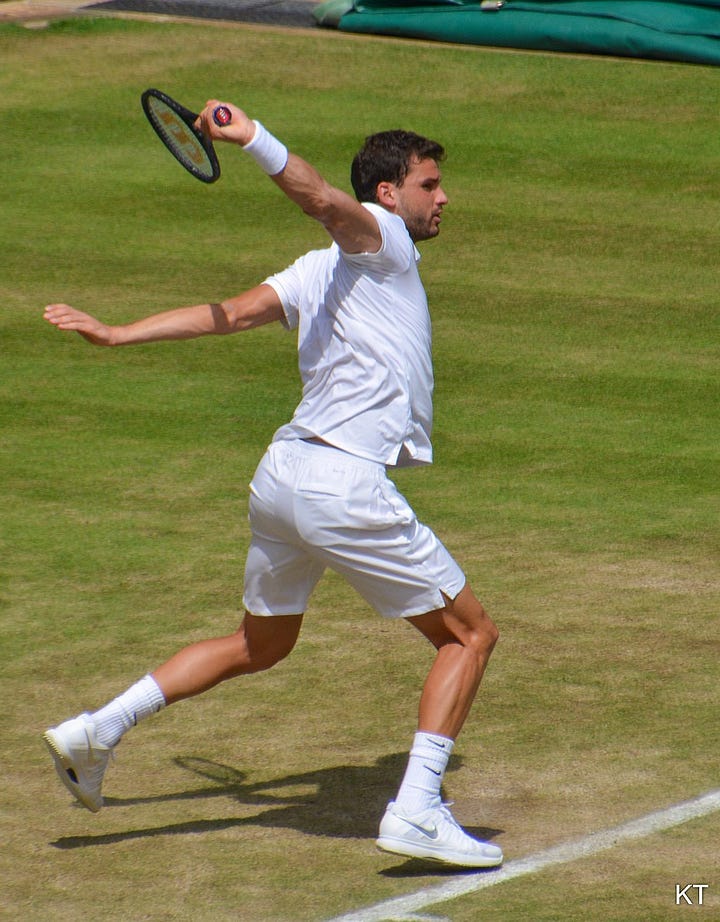

Few things in tennis get people waxing poetic more than a well-struck one-handed backhand. The cocked wrist and huge shoulder turn load the racquet tip high into the air before dropping into a long and unwinding arc that produces unrivaled spin and power and makes it the obvious aesthetic choice for many aspiring players. Observe this 103mph steamer from Richard Gasquet:

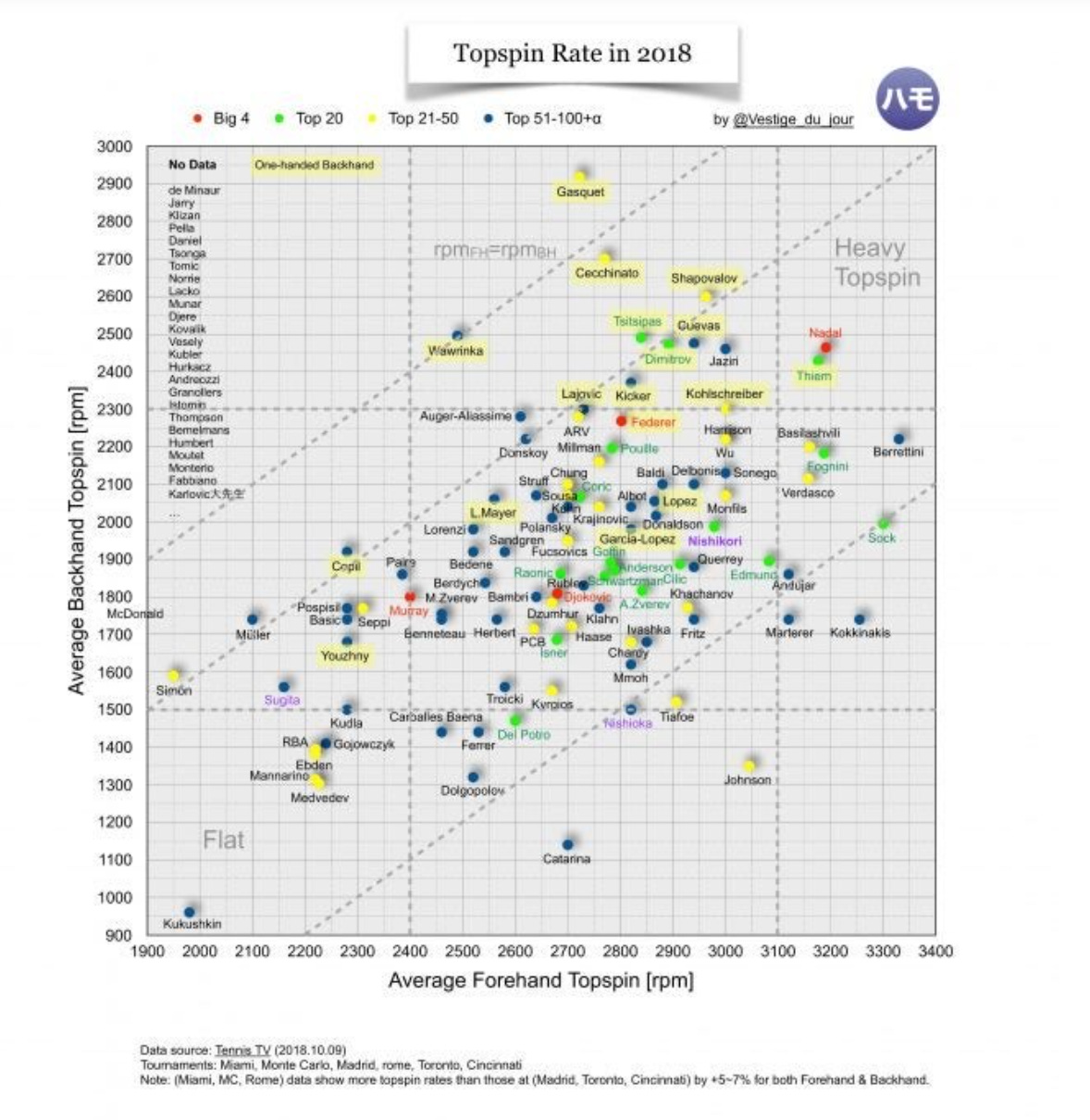

A popular 2018 graph from Twitter user Vestige du jour clearly shows a general pattern of spin dominance for the one-handed players, with Gasquet firmly on top:

And yet, at the professional level the one-hander has been on the decline for decades. In any given year roughly 10% of players continue to give it life support in the top 100. The current crop includes Tsitsipas, Musetti, Dimitrov, Evans, Shapovalov, Gasquet, Lajovic, Cecchinato, O’Connell, Altmaier, Wawrinka, and Thiem. Why it has declined I’ll get into later in the piece.

In a recent post, a Twitter user named “The Big Three” posted a thread (found here) arguing that Federer’s backhand struggled against Nadal more than Wawrinka’s because of the racquet angle during the drop and at the bottom of the swing.

While it’s impossible to answer this question definitively, it didn’t really sit as a satisfying answer to me, mainly because I don’t think a prime Federer did struggle more than Wawrinka et al. against Nadal, and also because a player who arguably had the most success against Nadal on clay—Dominic Thiem—often has an open racquet face just like Federer’s (and a similar grip).1

But the post did get me thinking about the one-hander more, and a few subscribers have asked for an analysis of the one-hander, and I am on a 14-hour flight to Vancouver, so let’s dig in.

Commonalities

There are certain traits in a swing that are shared by all players of the modern one-handed backhand. The unit turn is initiated with the non-dominant hand on the throat of the racquet. The racquet tip initially points toward high noon to create a lot of leverage with the wrist in an extended position. The left elbow often lifts to shoulder level to raise the racquet head higher in the takeback as the chin rests over the hitting shoulder. You can see in Dimitrov and Gasquet below that the tip is slightly pointing toward the opponent. This is creating even more leverage/a longer swing to generate more racquet head speed.2 From here the swing is "loaded" and ready to drop and rip.

If you see a one-handed backhand in the top 100 it really can’t deviate from this loaded setup too much without being heavily penalized, and of all the strokes the one-handed backhand is the one that is the most similar across the board in top players. All players rotate or unwind their hips and shoulders to some extent, but there are differences by degree, and these differences come with tradeoffs, and this is where my interest lies.

Differences

Grip: Perhaps the most important factor in the one-handed backhand is the grip. At the conservative end you have players like Dimitrov, Haas, and Federer. More extreme eastern backhand grips are seen in Kuerten, Gasquet, Almagro, Lajovic, and Shapovalov, and plenty of players are somewhere in between, such as Wawrinka, Thiem, Kohlschreiber, and Musetti.3

The more extreme grips are usually better suited to spin and handling higher balls as their more closed racquet face promotes a steeper swing path, and the more conservative grips tend to excel at lower balls and driving it flat, but that doesn’t mean we don’t get outliers. For example, Dimitrov has the most conservative grip of any one-hander but also registers huge spin, and while I don’t have any data, Almagro was always a pretty flat crusher of the ball despite a more extreme eastern grip. As always, swing paths, racquet setups, and tactics play a role.

Hitting-arm structure and swing length: Another point of difference is the hitting-arm structure during setup. At contact, the one-hander has a straight or near-straight arm, but when exactly the arm straightens differs from player to player. Thiem and Shapovalov are outliers in this regard, in that they straighten the arm extremely early in their setups and use high and long takebacks to generate huge power. Shapovalov's hitting hand (left) gets so high it is often at head height, with the racquet head parallel to the ground.4

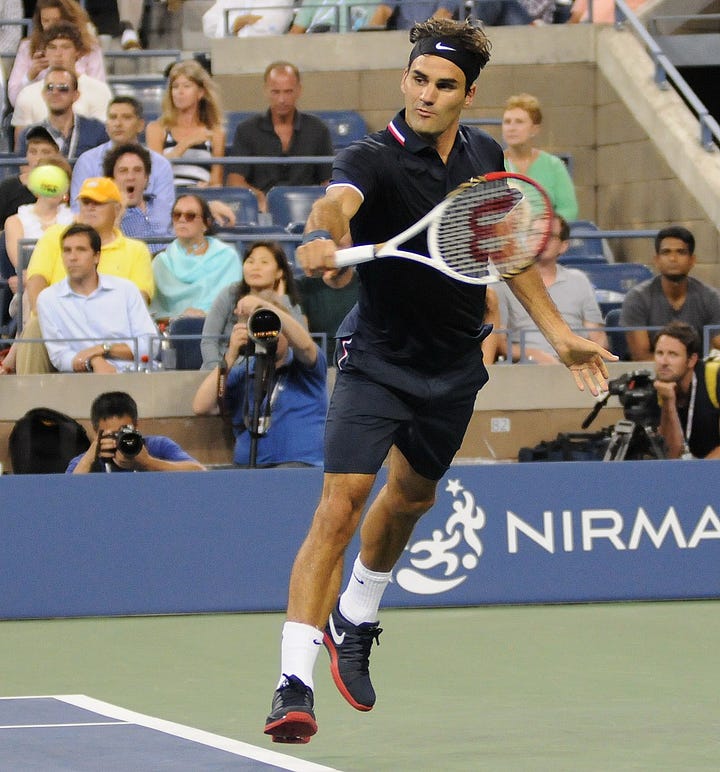

Compare this to Federer, who has a more compact take back and straightens very late, as seen below still bent well into the downswing.5 Haas, Blake, Gonzalez, Sampras, Tsitsipas, and Dimitrov are similar in this regard.

The perk of straightening the arm earlier is that it makes timing a little easier by reducing the degrees of freedom during the stroke; you can just release the shot with your non-hitting hand and let your hitting arm swing freely around your body. The downside is that the straight-arm setup probably reduces your power a touch and takes more time to prepare, so you usually require a longer swing to get power, and this in turn requires a deeper court position or you risk getting rushed.

Contact and follow-through: Follow-throughs vary based on the stroke hit, but the main distinction is how “open” the players are on contact and when finished and what the hitting arm, non-hitting arm, and wrist do post-contact. Generally, we see a more open contact position with the hips and shoulders more active/open for more extreme grips, as contact can be made further in front of the body with an extended wrist.

Almagro (and Kohlschreiber) are interesting cases because they use extreme forehands and backhands and return using the same side of the racquet. Observe Almagro’s sneaky switch on return below. It allowed them to hit mainly topspin returns as one-handers.

And the video below is more of a block return that he plays more closed/side on.

Return tricks aside, more conservative backhand grips tend to have a slightly more closed body during the swing/open up later and produce more of those arabesque finishes seen in Federer and Dimitrov.6

We can also note the role the non-dominant arm plays in the contact and follow-through phase. The non-dominant hand gets released from the racquet around the back hip before accelerating backward as a counterweight so that there is resistance to push against with the hitting arm. It’s often more pronounced on return or when abbreviating the swing (such as taking it early or on change-of-direction balls) but this occurs irrespective of grip and initial setups.

Is there an ideal for the modern game?

Many people will immediately think of Wawrinka. What does Wawrinka do that makes his backhand so good? Two things for me:

A smaller loop and takeback compared to most means he gives himself more time to prepare.7

Wawrinka keeps the racquet closer to the body with a lower left elbow and racquet head. Importantly, he is still storing plenty of power by keeping the racquet tip upright. Unique to Wawrinka (Thiem is a little like this) is the use of his hips and body to make his backhand more rotational and connected as he also straightens his arm quite early in the downswing. He doesn’t use the left-arm counterforce very much and instead lets his shoulders unwind more like a forehand. The racquet head finishes way behind his body.8

By using more hip and shoulder rotation, straightening the arm early, and relying on the bigger muscles of his body, Wawrinka can afford a compact backswing but still get huge power, and this is why I think his backhand is so good.9 He’s basically made it a simpler skill to execute. Compared to, say, Dimitrov, who must coordinate elbow and wrist angles with minute adjustments of wrist flexion around contact, and then use a huge left arm counterforce, Wawrinka’s is very simple. Check out this video of two of the best one-handed backhands of all-time. Note how Almagro uses the left-arm counterforce exceptionally well, which means he appears to "push" the backhand more, or swing in a more linear fashion down the court, whereas Wawrinka's racquet flies "around" his body more.

Both are amazing backhands that reduce arm and wrist action, and when I talk of global maximums in technique10 it's hard to argue against Wawrinka's rotational shot; he's evolved the one-hander for modern baseline conditions. But it is still a tough shot to play in the modern game for the simple reason that the return of serve is more difficult with the single-hander. Even with the tricks of Almagro (who flips the racquet), the two-hander offers so much more stability and control, and on the return that's what it's all about. And for the single-handers currently playing, the best way to improve their return is to improve their chip and block ability. If we look at the 52-week return ratings of the ATP tour it's not really a surprise that the top performing single-hander is...Dan Evans at #17. A man who barely plays topspin backhands. Next is Dimitrov, another excellent slice exponent, and then Gasquet (a block aficionado of first-serves). It’s probably also worth mentioning that they use more eastern forehand grips (as does Tsitsipas), so the change of grips is minimal for these guys as well, and was all features Federer had that allowed him to post great return stats. For players with more extreme grip changes, like Musetti, Shapovalov, Thiem, and Lajovic, the return ability is hampered as they don’t flip the racquet like Almagro. They too should look to do what Wawrinka does: chip the damn return. Players with great first-strike ability after the serve (Nadal, Federer, Berrettini, etc.) usually punish this tactic a lot, but as Wawrinka showed, putting plenty of returns in the court with depth is a great way to build pressure over time, and the tactic earned him three slams where he slayed Big-3 members each time.

A final thought. While Wawrinka’s backhand is pretty much accepted as the best backhand of the last 20 years, it wouldn’t be my choice if I could pick one. I’d still take Federer’s. One aspect that is often overlooked is how the racquet specifications both enhance and inhibit certain shots and abilities. Let’s take Gasquet and Evans as an example. Gasquet uses an extended frame, 324mm balance, and is very high in swingweight. It allows him to crush the ball 5 metres behind the baseline, but it’s also less maneuverable than Evans’ very headlight Wilson Prostaff. What do you see when you watch those two play? You see Evans able to adjust and flick short balls and slices close to the baseline and up inside the court, and you see Gasquet able to roll very heavy and hard balls from way behind the baseline. You don’t see them do each other’s shots very well, and I use these two as examples because they are essentially opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of equipment and tactic. Wawrinka used a hammer of a stick that was great for blocking returns and crushing balls from deep, but he didn’t have the passing ability or variation that Federer had, and he couldn’t play up in the court like Federer either. As always tennis is a game of tradeoffs, and the result of swing and equipment choices is a complex interplay of court position, speed/spin rates, and shot selection ability. An excerpt from the Federer piece:

…part of his [Federer’s] appeal was also the aggressive forecourt nature of his game in an era where, even for casual observers, implicit in that style was a degree of risk that was courageous and admirable. Wandering from the mode of topspin baseline attrition is usually a sign of fatigue or desperation, but Federer managed to splice power and spin with finesse in a way we hadn't seen before.

In the modern game I would rather have Wawrinka’s backhand in a rally, but as a complete package—the slice, half-volley, return, blocks, flicks, lobs, and passing shots— Federer’s backhand at his best was severely underrated. He went toe-to-toe with peak Nadal on clay (their 06/07 clay battles were always very competitive) and could adjust up in the court on the grass a week later with slice and flick passes. He traded heavy baseline blows for finesse with swing and equipment decisions (unconscious or otherwise). He could have had a better baseline backhand perhaps by using a heavier and more even-balanced frame, but it would have then hurt his ability to play up in the court with variation. Maybe the modern game rewards the Wawrinka backhand more, but that is up for argument.

I’ll probably come back and expand on this article in the coming weeks—I have some thoughts for the youngsters still out there on tour—but I’m releasing it as it is for now before Indian Wells gets underway.

Of single-handers only. Djokovic has had the most success of any player against Nadal on clay.

Almagro photo credit: robbiesaurus. Dimitrov photo credit: Christian Messiano.

Shapovalov photo credit: JC. Thiem photo credit: Francois Goglins.

Photo credits for Federer's backhands: Christian Messiano (left) and Charlie Cowans (right). Tommy Haas: Carine06. Stefanos Tsitsipas: JC.

Photo credits in order for Federer (top left), Dimitrov (top right), Federer (bottom left) and Federer (bottom right): slgckgc, Carine06, Christian Messiano, Kadellar.

Wawrinka phot credit: Fred Romero

Photo credits — Wawrinka: Fred Romero. Gasquet: Fred Romero. Haas: Carine06. Wawrinka: Carine06.

Thiem made adjustments to his forehand and backhand in 2019 that made his strokes more compact and was a huge reason for his success.

Lohse, K., Miller, M., Bacelar, M., & Krigolson, O. (2019). Errors, rewards, and reinforcement in motor skill learning. In Skill Acquisition in Sport (pp. 39-60). Routledge.

Just discovered your site. Really great stuff.

One additional point on technique: Thiem and Musetti have their thumbs on top of their pointer fingers, whereas most other players have the pointer finger on top. I believe the thumb-first affords a firmer grip and more locked wrist, whereas the traditional technique of pointer-first allows you to break the wrist on the follow through and roll over the ball easier. Would be interested to hear your take on this.

I asked and you delivered, thanks so much on this piece it was needed. I am seriously on the fence about switching to a one-handed backhand from my two-handed backhand and wanted a more technical input about it rather than "they time it well" or "they've used it since they were kids" so I really appreciate the time gone into this analysis which I will refer to a lot.

I do have a few questions.

1. What do you think about the "simpler" approach to the one-handed backhand by Wawrinka on a much faster court with his racket specs coming in so heavy?.

2. Is an open stance one-handed backhand on the regular a viable shot in the modern game or a fad? I did see this brought up in a forum a while ago and thought it could cut down time for preparation for players like Wawrinka or Gasquet that swing super heavy frames when playing on a quicker court?.

3. Is it possible for someone wielding heavy rackets like Wawrinka and Gasquet play much sharper, harassing one-handed backhands in a similar manner to Nikolay Davydenko in which he could pick up the ball on the rise and cut it off extremely early robbing time off opponents and also neutralising any special effects added on the ball (spin) and playing ridiculous angles, is this a realistic shot that kind of heavy frame allows a player have in his repertoire provided they are strong enough?

Thanks again and have a safe flight.