Hubert Hurkacz edged Andrey Rublev 6/3 3/6 7/6, saving a match-point at 6/7 in the third-set tiebreaker with an ace, to clinch his second Masters 1000 title (Miami 2021 def. Sinner) and put himself in contention in the race to Turin, jumping 5 spots to number 11.

It was another masterful serving display from the Pole, who fired 21 aces (for 0 double faults) and won 81% of first-serve points. Leading into the final Hurkacz had absolutely crushed the serving stats:

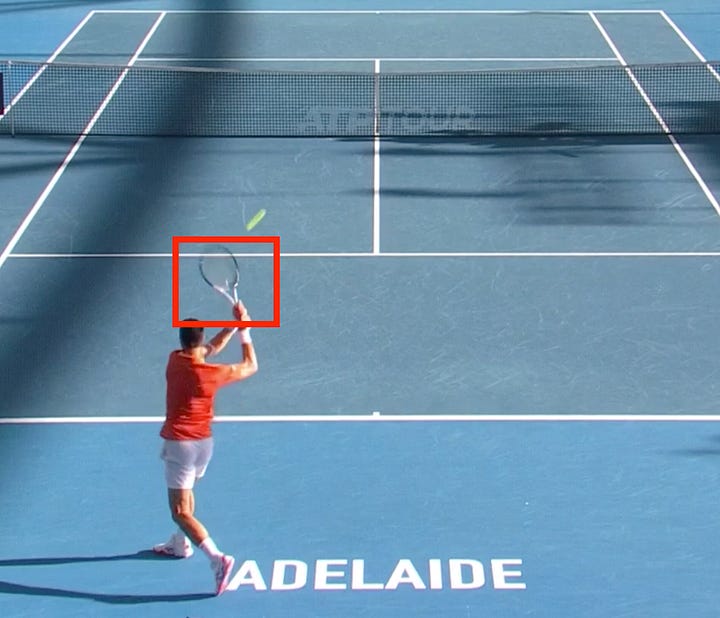

A look at Hubi’s mechanics showcases a key feature of great servers that I have touched on here and here. Understanding and identifying these mechanics makes a player’s performance on a particular shot a little more predictable. An excerpt:

The arm position that helps develop a heavyweight serve is the internal rotation of the shoulder prior to acceleration with the leg drive (there are other factors of course).

In the above quote, I used an image of the all-time ace leader, Ivo Karlovic, alongside MLB slinger Stephen Strasburg, to highlight the similarities between powerful throwing and powerful serving. Here it is again:

Here’s an excerpt from Technique Development in Tennis Stroke Production (emphasis added):

“The shoulder is the funnel for the transfer of energy from the trunk to the racket arm… The pause in changing racket direction from backswing to forward swing should be small to optimise the return of elastic energy to the concentric muscle contraction responsible for this forward motion.”

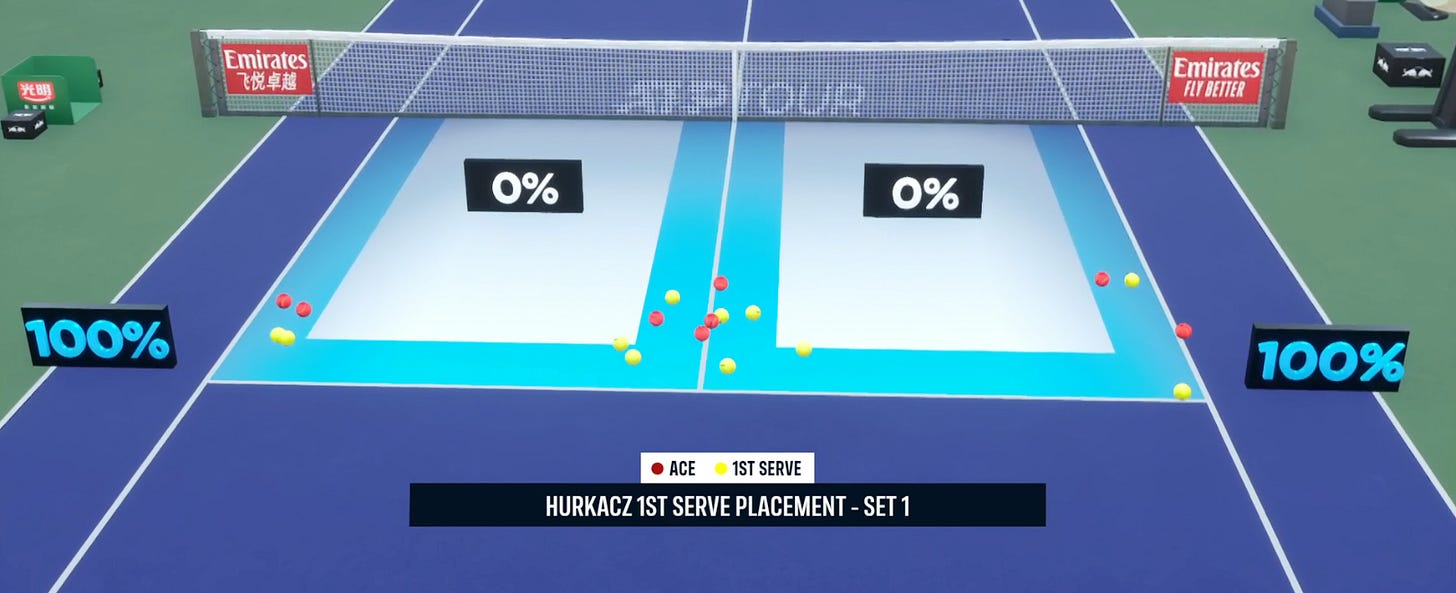

Not only is it a fast serve, but in the first set the Pole’s serve accuracy was very impressive, finding the lines of the service box (within ~2 feet) every time:

And while the serve is absolutely a heavyweight shot, Hurkacz’s game is in a similar mold to other giant baseliners Alexander Zverev and Daniil Medvedev in that they all are considered counterpunching baseliners. They also move incredibly well for their height, but all lack a huge “plus-one forehand” after the serve like the previous generation of top-tier tall players (such as Soderling, Tsonga, and Berdych). Similar to Zverev, Hurkacz’s forehand has that flexed-wrist/outside set-up that is increasingly seen on the ATP tour these days, and it is the shot that can let him down when under pressure:

And what about Rublev? Well, he has one of the simplest and most vicious actions out there. A very upright racquet head and compact swing means he has very little to “undo” as he unloads on the ball. Just drop with gravity and unwind:

Conversely, Hurkacz’s backhand is a very effective shield that enables him to stay in rallies and apply pressure on return games. Like other effective flat backhands, Hurkacz employs the “locked-wrist” follow-through where the racquet tip points left (from a back perspective) and is a commonality he shares with Djokovic, Fritz, Korda and—at times—Alcaraz.

TennisTV commentator quotes on Hubi’s backhand:

“One of the flattest two-handers in the men’s game, Hurkacz.”

“That’s why it’s tougher to attack off that backhand, isn’t it? Because it’s so flat and stays so low. It’s a hard ball to change direction on.”

“Yeah, the backand is really effective. It’s such a strong shot. He might not hit a lot of winners, but it’s really tough to attack. He holds his position well. Very effective shot.”

And what about Rublev’s relatively more fragile backhand? Well, he tends to “roll” his wrists through contact. It may help him get a little more spin, but it makes timing the ball more difficult with his initial outside setup position.1

And so the potential of these contrasting baseline abilities—Rublev’s forehand being superior to Hurkacz’s, yet the inverse occurring on the backhand wing—is often baked into the technique. Swing mechanics can predict much.

As I’ve said before, “technique dictates tactic” and what we found on Sunday was Hurkacz looking for Rublev’s backhand, and Rublev looking for Hurkacz’s forehand. In the backhand exchanges in particular, Rublev went down the line (into Hurkacz’s forehand 37% of the time), whereas Hurkacz was happy to trade through the backhand channel, only taking his backhand down the line 25% of the time.

The tie-breaker was highly entertaining.

In contrast to their strengths, Rublev raced out to a 3-0 lead off the back of some impressive backhands down the line as well as a timid backhand miss from Hurkacz.

Then normal habits resumed.

The Pole fired two aces.

At 3-2 Hurkacz missed a forehand long and Rublev then earned a serve-plus-one forehand to lead 5-2.

At 5-2, Hurkacz missed a first serve and Rublev was finally in a rally on the Hurkacz serve, two points from the title. This is where the merits of a shot are truly tested (if you will remember Hurkacz at Wimbledon playing Djokovic, his forehand broke when presented with chances also). If there was a shot that was predictably going to break, it was the Hurkacz forehand or the Rublev backhand.

Rublev pulled a very easy backhand wide. 5-3.

The next point Hurkacz fired another unreturnable serve. 5-4.

At 5-4 Rublev missed another backhand return off a weak second serve (an area of his game that I have also written on as a weakness). 5-5.

On the next point, the Russian found a wide serve to go ahead 6-5 with a match point.

Hurkacz fires an ace out wide at 218 km/h. 6-6.

Change ends. Hurkacz walks up to the line, ace down the T at 226 km/h. 7-6.

Now down match point, Rublev rips a few balls into Hurkacz’s forehand that the Pole timidly brushes and pushes long. 7-7.

But at 7-7 Hurkacz finds a forehand down the line that was beautifully placed. 8-7. A rare forehand winner under pressure.

Then Rublev gets a great read on Hurkacz’s 227km/h serve out wide and manages to find an inside-out forehand later in the point that he rips for a forced error. 8-8.

Hurkacz fires an unreturnable serve out wide at 202 km/h. That’s now 6/9 serves in the breaker that didn’t get returned at all. Match point Hubi.

And here I thought Rublev didn’t look to go to Hurkacz’s forehand down match point again. In fact, although it was a 16-shot rally, Rublev only hit one ball into the Hurkacz forehand corner. Hurkacz redirected a flat backhand down the line after some great defence, and Rublev then rushed a forehand into the net.

It’s easy to see from the couch—and with the benefit of hindsight—that Rublev perhaps should have gone to the Pole’s forehand again in that moment, but it was a great display of how strengths and weaknesses are often magnified in pressure situations, and in the end, it was perhaps just one poor decision that changed the outcome of the match.

This was a quick and late recap, but I’ll be back soon with some thoughts on Pickleball and Padel tennis in a more long-form piece, as well as some coverage from either Tokyo, Antwerp, or Stockholm.

See you in the comments.

Hi Hugh, great analysis as always.

That final set tie-break was such a great encapsulation of what this substack taught me over the last months.

Even though he lost to a firing Hurkacz (who is looking more and more like an ATG server, feels like just like Isner in his time he can fire an ace whenever he wants to), Rublev is undeniably having his best year results-wise.

However, I can't seem to find any noticeable change in his game, technique or physical-wise. So I personnally give it to a bit of draw luck and tactical/mental improvements/being braver in his shot selection (that BH DTL he pulls off to make it 3-0 in the tie I don't think he tries it last year, for example).

However, one reddit user I follow because he has great technical knowledge and has a similar approach to you (JimKirk1) said he actually tweaked his backhand and it's now a fuller takeback (still noisy, but fuller) that allows him to try those riskier shots. But I can't seem to see it. If we focus on those 2 easy misses, yes he isn't quite 90° facing the net but he is far from a 180°/back fence also (additionnaly to serving down to up). Have you noticed any change?

Another great read! But Sinner does the same rotation thing with his BH. Doesn’t he?

Also, what about Rublevs 2nd serve. Seems like a weakness too.