Djokovic v Korda: Adelaide Final Analysis

locked wrist backhands—changing directions—clutch play

Novak Djokovic saved a championship point to clinch victory over Sebastian Korda 6/7 7/6 6/4 in 3 hours and 11 minutes in the final of the first Adelaide International 250 on Sunday. It was the 16th time the Serb has won from match points down (Djokovic has only ever lost 3 (!) matches from match-point up. Wild).

Early exchanges showcased the technical excellence of both players. Back in March of last year, I wrote a short piece on Korda. An excerpt:

“What I love about his game is the simplicity in all his strokes. At 6’5’’ there is an easy tap of power that is reminiscent of Tomas Berdych. His 52-week serve statistics are promising, although not crazy considering his height. What makes me bullish on Korda overall is his return-of-serve ability; he currently sits at 28 in the 52-week ATP return rating, and if we look at hard court matches only against top-10 players, he rises to 17th, just behind Daniil Medvedev and Emil Ruusuvori. Such a well-balanced game lends itself to really reap the rewards if Korda can take his fitness and athleticism to another level in a similar fashion to what Medvedev did in 2019. It should be expected that his serve improves into his twenties as he builds up more strength as well.”

Despite a relatively lackluster 2022, Korda’s ‘ATP Return Rating’ has improved to 15th, and he showcased why on Sunday, where newfound confidence has him looking very dangerous in the quick Australian conditions.

First set

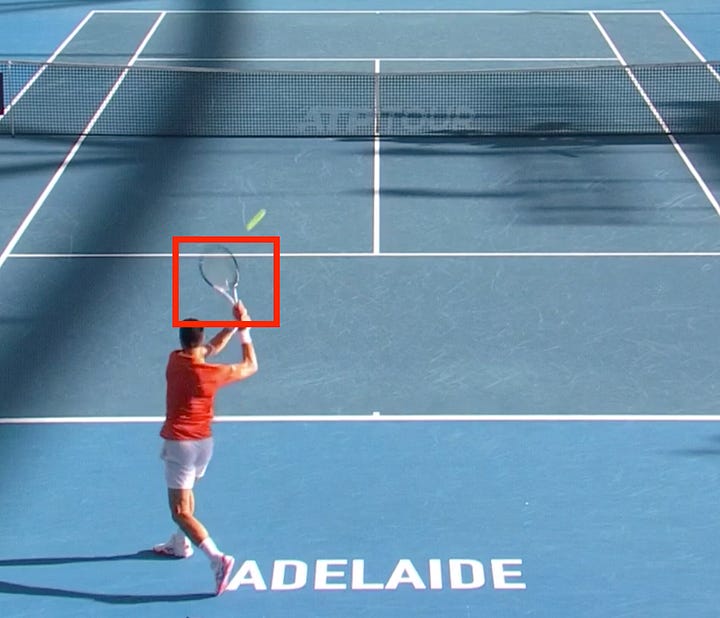

Both men displayed an ability to change direction easily off both wings, and Korda’s baseline game was the superior of the two in the opening set with Djokovic looking a little fatigued, defensive, and off-balance at times. Korda’s backhand down-the-line in particular created plenty of headaches in the opening set. Then, with the young American serving for the first set at 5-4 40-0, Korda made five backhand errors in a row—one was an absolute sitter on top of the net. Up until that point his backhand had been world-class. That’s pressure, combined with Djokovic down the other end. The commentators mentioned midway through the first set after this passing shot:

“I think him [Djokovic], Rafa, Andy…when they/re playing their best, they’re just scrambling, something that you’re like “How on earth?” and then making you play another shot, and then another one, and never anything easy, and it starts draining you.”

Korda regathered, however, taking initiative in the big moments of the tie-breaker—again with his backhand—and he closed out the first set on his seventh set point.

Korda looked very comfortable exchanging backhands for most of the match. He has traits that are similar to Djokovic in the follow through, however, his set-up is outside the hands. It’s very similar to Taylor Fritz’s backhand and both these guys excel on hard courts with their flat penetrating strokes.

Locked wrists

Korda’s follow-through has locked wrists, meaning the wrist position on contact is maintained post-contact. Joel Myers has an Instagram clip explaining the same trait in Djokovic’s backhand (second clip of the post). We see the same thing in Fritz and Alcaraz (sometimes).

Inside v outside

However, Korda starts his backhand outside the hands, something I think makes timing and topspin a little more difficult. There are exceptions, however, and one thing that makes it viable is having a flatter swing path and/or more conservative grip setup. A flat swing path and conservative grip are seen in the backhands of Norrie, Fritz, Kyrgios, Paul, Tiafoe, and Hurkacz. I wrote last week of tradeoffs, and I think here the distinction is usually due to court position. If you want to play up in the court and be aggressive, starting outside with a flat swing path might save you time, but my hunch is that the very best tend to still get the racquet with a full turn. Safin, Davydenko, Nalbandian, Rune, and Djokovic have (had) no issues on quick courts or with aggressive court positions.1

Change of direction

One thing that is not well quantified in tennis is tracking how often players change the direction of the ball. It is often discussed how well Djokovic can change directions during rallies. It’s a weapon that doesn’t appear on stat sheets directly unless you end up actually hitting outright winners off your changes, but watching Korda give Djokovic a taste of his own medicine on Sunday was eye-opening. It shows that you don’t need huge spin and power to dominate the best movers if you have directional control. ‘Stats on the T’ did a review of change-of-direction metrics during the 2020 French Open. It showed that Nadal dominated opponents in change-of-direction, but there was one player who created more angles when they played each other, and that was Djokovic. On both serve and return the Serb gets players moving. It’s easier said than done. An excerpt from the Stats on the T article:

“Yet this also reminds us that a high degree of redirection is likely to come with a lot of risk and this turned out to be Novak’s undoing against Nadal in their last Roland Garros meeting.”

Changing direction has risks, of course. The net is higher and the court is shorter when going down the line. But with simple mechanics Korda did it over and over again to great effect, and it’s a skill that few players have off both wings.

Many players are adept at changing directions with the forehand, but the backhand down-the-line is a shot that I think has been a major reason for the plateau in results of several players that come to mind: Auger-Aliassime, Rublev, and Berrettini. If you can’t threaten opponents with a line backhand during exchanges, they aren’t going to feel as much pressure once they find your backhand. Of course, those three players mentioned all have great forehands, so they look to run around more than most, but in the matches I have covered of them—especially Felix here—his backhand has been his Achilles heel, and one that I think will stop him from making significant strides further up the ranking unless he makes changes.

Clutch play

As I mentioned in the opening paragraph, Novak has now won 16 times from match points down and has only ever lost 3 matches from match-point up. While deep dives into “clutchness” haven’t shown Djokovic to be significantly greater than most other players (unlike Kyrgios) on big points, he has a style that balances aggression and safety that is so well suited to modern tennis, and he commits point-after-point. An extract from a Tennis Abstract piece:

“…of the most effective returners, Novak is the one who splits the difference between staying safe and swinging big. Or, more accurately, he is able to play both ways as the situation demands.”

The ATP’s “Under Pressure” leaderboard—calculated by adding the percentage of break points converted and saved, percentage of tie-breaks won and percentage of deciding sets won—shows that he outranks all his peers since this kind of data has been available. A familiar group, plus a future star:

Heading into next week’s Australian Open, he’s still firmly the man to beat. Young guns like Korda and Holger Rune will be dangerous, and Medvedev, Tsitsipas, and Fritz look in form, but the gap between him and the rest is still significant, and he’s been dominating tough matches now for several months.

Every player at times swings from the outside: on return, when rushed, etc. in these moments you have to shorten the swing otherwise you will be late. My issue is when players have time. In that instance, I think a full turn is better.