Technical weaknesses with the Tsitsipas backhand

the setup — stances and drop steps — eye dominance — returns — all that is old is new again, or, what Tsitsipas needs to change

Note: Lots of gifs and a long piece. Best viewed with good internet and a big screen.

“While fitness, motivation, and tactical prowess are undoubtedly important attributes in tennis, the mechanical efficiency of an individual’s strokes often determine the level of success experienced by the recreational, competitive, and elite tennis player.”

— Reid, M., & Elliott, B. (2002). Tennis: The one‐and two‐handed backhands in tennis. Sports Biomechanics, 1(1), 47-68.

Few examples illustrate this quote better than Stefanos Tsitsipas’ backhand struggles. In 2024 the Greek ranked among the worst in Tennis Insights backhand winner percentage relative to in-play percentage — a damning stat for a player with top-five talent.1

In a previous interview with Gill Gross, I was asked if Tsitsipas’ backhand was fundamentally sound. My answer then — and now — is yes, but "fundamentally sound" can be a dangerously low bar at the elite level. A stroke can check all the basic biomechanical boxes and still be technically inferior to its peers for reasons rooted entirely in mechanics.

“The more you learn about the biomechanics of strokes, the more you realize how much the benefits or limitations of certain techniques are variable and contextual.”

— Duane Knudson, Biomechanical Principles of Tennis Technique

This line from Duane Knudson has always stuck with me when assessing pro strokes, because it suggests that many issues are less about violating fundamentals, and more about how their particular swings move within them.

So I started to devour a lot of Tsitsipas footage (I obsess so you don’t have to), and a lot of footage of other great one-handers from more recent eras: Kuerten, Gaudio, Almagro, Gasquet, Wawrinka, Kohlschreiber, Federer, Thiem.

This piece is about those differences: the cumulative, almost hidden, biomechanical flaws that, when stacked on top of each other, turn a "technically sound" backhand into a liability.

The setup

Professional one-handed backhands tend to vary less than other shots in their setup, because the grip and nature of the shot constrains what is possible to make an effective swing. Some YouTube coaches have lauded Tsitsipas’ backhand for its ideal setup position, where the strings point to the side fence with the racquet tip able to “balance a coin on the top”, and the non-dominant elbow lifted very high:2

While this position may be a helpful cue for amateurs to ensure they close their strings in the drop, Tsitsipas’ setup is rarely a position we’ve seen in the crème de la crème of professional backhands. Observe the direction of the racquet tip in the following setups, as well the location of both elbows.

I tried to time them all where the ball was at a similar point/slightly post-bounce, with players just stepping onto their front leg.

You can see that there are various setup positions and backswing lengths among these pros, but note how all except Tsitsipas have their racquet faces more open (towards the sky to some degree), and slanting on an angle over their non-dominant shoulder; you want that coin falling into your back pocket.

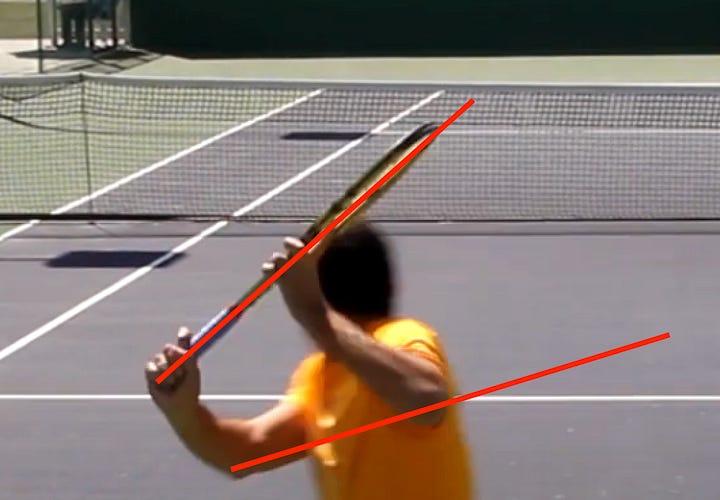

What is important to observe here is that there is a relationship between a player’s elbow positions and the racquet orientation. More compact backhand setups, like Federer, Tsitsipas, Gaudio, and Wawrinka, have lines more upwards, as they keep their hitting elbow/hand lower, whereas longer backhand setups, like Kuerten, Shapovalov, and Gasquet, produce more horizontal lines, as they take their hitting elbow/hand back higher and/or straighten the hitting arm earlier.

Whether the lines are more horizontal or more vertical, what is important is that they move up towards the right (for a right hander, like in the above images, except for Tsitsipas), signalling that the racquet head is going to be dropping more on the inside of the hitting hand. That is, the higher the non-dominant elbow gets, the higher (or farther away from the torso) you want your hitting elbow to get, so that you can help maintain this ‘pre-slot’, or ‘inside’ racquet position in the setup.

What gets Tsitsipas into trouble is that he keeps his hitting-arm very low and tucked. This alone is not a flaw. What kills Stef is that he pairs this tucked/low right arm with his non-dominant elbow getting very high, meaning his racquet head is poorly situated to drop into a good slot position.3

Here’s an example:

Familiar readers may have started to develop an eye for seeing the traits that emerge in so many suspect shots: a lack of in-to-out path, coupled with a cocktail of moving parts in the moments before contact (wrist, elbows) that are simply not there — at least not in such an extreme degree — in some of the best exponents.

Let’s look at the greats of the last 25 years, with an emphasis on their setup position, and their slot position, which I will pause at its maximum depth.

Keys to look for:

How far back does the racquet tip get? The strings are visible behind the torso.

Notice how the non-dominant elbow also, therefore, gets a long way behind the torso in the depths of the backswing.

Note the space between the hitting elbow and the torso in the setup.

Notice how early the hitting arm extends (straightens), making the swing into contact very clean. There’s very little movement from the arm or wrist. It’s the shoulder that moves.

Kuerten

Gaudio

Gasquet

Wawrinka

Almagro

Thiem

Federer

Kohlschreiber

Notice how all these great backhands “pair” or sync their elbows. If the hitting elbow is lower and closer to the torso, the other elbow stays lower as well (Federer, Gaudio, Wawrinka a bit), and if the non-dominant elbow gets higher, the hitting elbow/hand gets pushed farther/higher from the torso (Gasquet, Thiem, Kuerten, Almagro). This ensures that the arm and racquet have a longer in-to-out runway before contact, or that the racquet has a long runway on the “transverse plane”, to use a ten-dollar term. Depth of swing always trumps height of swing. This is important because research has shown that single-handed backhands require more time to create their maximum pre-impact horizontal racquet speeds compared to two-handed backhands.4

Now some astute observers may have noticed that I have used a neutral stance example from Tsitsipas, but used closed stances for most of the others, thereby exaggerating the differences in slot position.

Well spotted if so.

It doesn’t change much for the best:

Nor does it help Tsitsipas’ case. Most examples of matchplay show how he rarely gets the racquet tip very deep in the slot, even when playing from more closed positions. It’s an incredible short and busy motion:

But here’s the other interesting thing about Tsitsipas’ backhand…

Stances

More than any other player I have closely watched, the greek opts to play neutral (front foot down the court, or towards the net like Kuerten above) stances on his backhand far more than other single-handers.5

There are times when front foot backhands are beneficial: you’re moving forward to steal time, or perhaps to catch a ball from getting too high (or too low), or you want to easily inject pace with your body momentum.

Here’s Kohlschreiber sweetly timing one against Nadal:

Federer in 2017 became much more willing to do this as he upped his aggression:

But outside of taking the ball on the rise and flattening it out, the best strikers of the backhand tend to hit a lot of backhands from more closed stances as this naturally turns the hips and shoulders more.

Wawrinka, Federer, Gasquet, and Kohlschreiber were excellent at this, and below is an example from Wawrinka, where he uses a drop step to get more side on to this Djokovic return coming into his body.

The drop step here facilitates an in-to-out swing as it automatically turns your hips and shoulders more, irrespective of racquet setups:

Ditto Gasquet. Look how far back the racquet head gets in the depth of the backswing as he creates a closed stance from middle rally situations:

I don’t think I’ve ever seen Tsitsipas use a drop step on his backhand. Part of this is probably how forehand hungry he is; drop steps are more common when the ball is coming more toward you, and Tsitsipas is great at finding forehands, but the point remains that the Greek gets himself in a closed position for backhands less frequently than his single-handed peers. Like the first gif I showed of him in this article, he usually just steps forward, irrespective of position and shot selection.

I wonder if Patrick Mouratoglou had an influence on his backhand development. He certainly emphasises the exaggeration of the elbow and wrist to hit the ball (which is not seen to a large degree in the great single handers I’ve just shown), as well as using a neutral or even open-stance foot position based on eye-dominance (Yes, seriously. Everyone now, let’s roll our eyes together). Eye dominance is another piece piling up in my drafts, but some important quote(s) I’ve assembled thus far (emphasis added):6

“…tennis is not primarily an aiming sport. The critical visual components in tennis are depth perception and binocular visual acuity (as well as peripheral awareness?). With these two components, the direction and speed of the ball can be anticipated.”

“Body position is probably judged in relation to these fixed reference points and this is the means by which aiming is achieved.”

— Orient, L., Squad, G. J., Dom, C., & Rifle, D. C. A. F. Eye dominance in sport. Eye, 87, 3-1.

I can’t un-see this Tsitsipas backhand footwork anymore. It’s so common compared to all the other one-handers, and I wonder if the footwork is somehow related to the swing. Maybe he needs to be more open with his body to allow his hips and torso to fire more aggressively, as he lacks arm speed given how bent and upright the swing is, much like a two-handed backhand.7

Such compensatory movements do little to stem the damage. While the first graph in this post displayed Tsitsipas’ poor winner-to-in percentage numbers, even when the Greek does manage to find his backhand inside the lines, it makes for sober reading. TennisViz provided me with some one-handed analysis of tour players, and what stood out to me were the numbers in the bottom of the spreadsheet: a high net clearance, a high percentage landing short, and a high percentage landing in the middle of the court.8 That translates to batting practice for the Sinner’s and Alcaraz’s of the world.

But perhaps the sorest point of Tsitsipas’ backhand woes occur even before rally situations unfold..

Returns

Nowhere is Tsitsipas’ backhand more susceptible than on return. The serve is the fastest shot in tennis, and if there is one way to expose Stef’s slice-deficient/high-takeback/low-depth backhand return, it is to rush it when serving.

Only recently in Indian Wells we heard Andy Murray give this return advice to Novak Djokovic during a match:

“Novak, prepare at the height of the ball on the return.”

In that instant I’m guessing it was about Djokovic getting his hands and racquet higher in the bouncy Indian Wells conditions.

Getting your hand/racquet at ball level for first-serve returns is necessary as it’s more of a blocking shot; you don’t need racquet head speed as much as the ability to quickly find good contact angles when deflecting 200+ km/h serves.9

Given Tsitsipas’ stubbornness to return serves from closer to the baseline a la Roger Federer, he would do well to take note of how low and compressed the Swiss kept his elbows and racquet head when doing so:

I mean, everyone remembers that backhand return that Federer hit from on the baseline against Roddick’s 140mph serve.

And while this takeback is natural for Federer as he always takes his left elbow low, there are other examples of players with higher elbow lifts operating a very compact swing for returns specifically.

It’s been six years since Tsitsipas first broke into the ATP top 10 as the ‘next big thing — and oh look, he’s got a one-hander!’ Back then his backhand was the clear weaker wing, but he masked it with a youthful confidence and a lack of scar tissue. It was more ornamental, less fatal. That’s no longer the case, and more perniciously, over the past decade the game has only gotten faster. Even de Minaur is rushing Tsitsipas on returns more than most of the Greek’s original top-10 contemporaries he first encountered:10

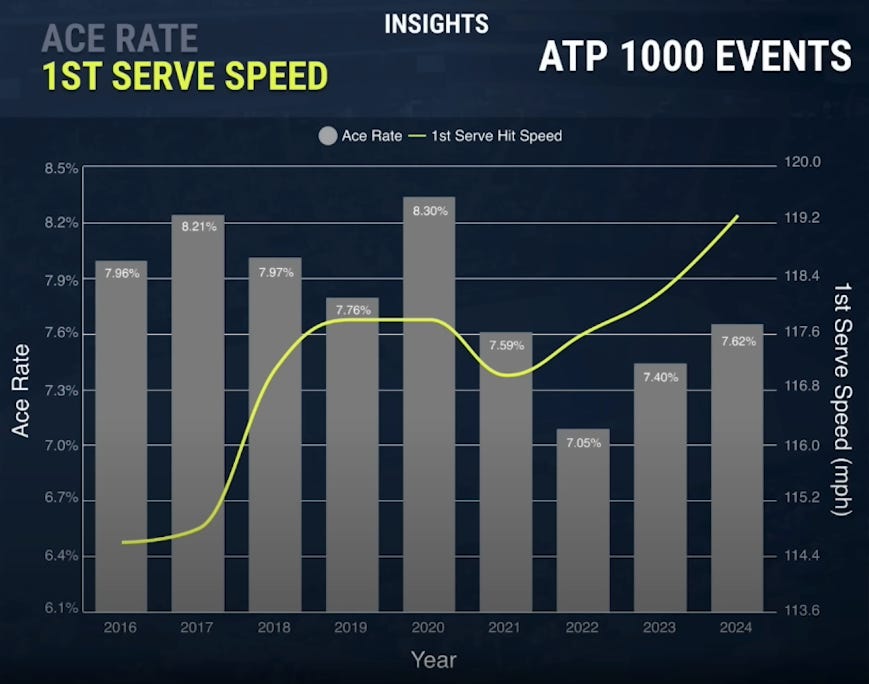

If you’re more of a visual learner, Gill Gross recently aired some Tennis Insights data with this graph on serve speed trends at the Masters 1000 events over the last nine years, showing an uptick in first serve speeds of ~5 mph since 2016:

Such a trend makes one wonder: can the single-hander survive in this frenetic era we find ourselves in?

Lorenzo Musetti is keeping it on life support in the top 10 for the moment, and at first glance he has a very Tsitsipas-ish setup:

But there are several stylistic differences beyond their setups that make Musetti’s backhand far more robust: the Italian creates more space with his hitting elbow, uses a more extreme grip, stands much deeper to return (and in rally), can block returns very effectively, slices in-rally far better, and plays more closed stances. And for all that he still doesn’t spit out all-time-great backhand numbers or vibes (go back to the top and check where the Italian landed on the Tennis Insights chart with the black circle). He’s also got a very skewed natural surface resume, where the time afforded on clay, and the slice-friendly nature of grass, mask his topspin weaponry in fast play.11 He is yet to crack the code on hard courts, and maybe Thiem will be the last for some time.

Or maybe…

All that is old is new again, or, what Tsitsipas needs to change

If there is one single-hander that I am curious to follow, it belongs to a young Swiss: Henry Bernet.

I first caught a glimpse of his game when he won the Australian Open Junior Boys title in January:

In four minutes and 10 backhands I can tell Bernet will have a degree of proficiency on his topspin one-hander that Tsitsipas could only dream of.

Look how low and simple the backhand return is:

TC Old Boys producing the goods again.12

Perhaps Bernet is the blueprint for the one-hander going forward. The ‘power position’ is toned down, but the slot position is beautifully deep. And as I wrote earlier when observing the great single-handers: depth of swing always trumps height of swing.

Maybe this technique will become ubiquitous in future one-handers, and it should be no surprise to see that it has emerged in a youngster, whose game has been built from within the faster playing environment..

But this isn’t anything new. We are going Back to the Future in terms of setups.

Laver. Llendl. Muster. Vilas. Korda. McEnroe. Depth always trumped height.

Given all this, the real question is: “what should Tsitsipas change?”

There are numerous setup changes he could make, but the easiest, and most obvious adjustment would be to play more closed stance backhands.

Doing so would help facilitate a better in-to-out swing without having to make any adjustments to the swing itself. In my viewing, he hits the backhand better when doing this.

Of course, this isn’t always possible — especially on return — so I would look to Kohlschreiber for inspiration as a model for playing a low left-elbow return backhand. Adding that to the toolkit would do wonders for his return woes. Such suggestions reminded me of this quote from a prior piece:

Technique is really just a form of technology.13 You can use it to leverage your capabilities beyond what is possible without it, just as the fastest runner can’t keep up with a mediocre cyclist. That’s why I’m prone to saying that tennis is a backswing game. How you set up for shots dictates what kind of tech you’re playing with.

The problem with Tsitsipas’ backhand isn’t that it’s a one-hander—it’s that it’s a compromised one. It mimics the form without mastering the function. In today’s game, that’s not enough. The one-hander, when built right, is still a viable weapon (just ask Wawrinka, Federer, and Thiem), but it has to be biomechanically precise. Tsitsipas has the raw talent to rebuild it. Whether he chooses to do so, or whether he continues to rely on a motion that flatters only to deceive, may define the rest of his career.

Not a knock on 2 Minute Tennis (I’m a fan of his channel), as he was specifically referring to amateurs. I don’t have much experience working with amateurs with a one-hander.

Like Federer, Sampras and Blake kept their non-dominant arm well tucked. Sometimes Thiem appears to have this lack of in-to-out path but could consistently deliver huge power and control. The reason his worked is that he straightened the hitting arm very early, so he created a lot of horizontal space early (longer runway) to build speed, but by virtue of that also had very few moving parts in the forward swing courtesy of the early straightening. So he often hit winners with a lot of sidespin/flat, but he could control that. Regarding Thiem’s straight setup, note this excerpt (emphasis added):

“Conceptually and in general terms, comparable linear racquet velocities at impact are achieved by either increasing the radius of rotation of the racquet swing in the 1BH, and by increasing angular velocities because of a shorter hitting radius in the 2BH technique.”

— Genevois et al. (2015)

Reid, M., & Elliott, B. (2002). Tennis: The one‐and two‐handed backhands in tennis. Sports Biomechanics, 1(1), 47-68.

For a review of relevant literature of the one and two-handed backhands see also:

Genevois, C., Reid, M., Rogowski, I., & Crespo, M. (2015). Performance factors related to the different tennis backhand groundstrokes: a review. Journal of sports science & medicine, 14(1), 194.

Note that all players use all the stances (open, neutral, closed), but I am saying Tsitsipas often chooses neutral more often, where a lot of others would use closed.

Orient, L., Squad, G. J., Dom, C., & Rifle, D. C. A. F. Eye dominance in sport. Eye, 87, 3-1.

“Thus it is evident that the 1BH and 2BH involve different strategies to develop horizontal racquet velocity at impact. Indeed, 2BH strokes rely comparatively more on trunk rotation whereas the 1BH does the same with the rotations of the upper limb joints of the hitting arm (Kawasaki et al., 2005).”

— Excerpt from Genvois et al., (2015) (Full citation in footnote 4)

— Kawasaki, S., Imai, S., Inaoka, H., Masuda, T., Ishida, A., Okawa, A., & Shinomiya, K. (2005). The lower lumbar spine moment and the axial rotational motion of a body during one-handed and double-handed backhand stroke in tennis. International journal of sports medicine, 26(08), 617-621.

Tennis Viz analysed players: GMP, Kovacevic, Dimitrov, Eubanks, Lajovic, O’Connell, Wawrinka, Evans, Musetti, Gasquet.

I’ve seen a chart from Hawkeye data in a book called Tennis Science by Reid, Elliot, and Crespo that showed top male players averaged ~12 inches of net clearance on their first serve returns, a good 4-6 inches lower than their second serve return and rally ball average net clearance. An excerpt from the book (pages 70-71) related to the graph:

“…net clearance for the majority of male players is shown to be less on first-serve returns, intuitively brought about by a player’s need to keep their swings short, with less opportunity to impart spin on the ball.”

When Tsitsipas first moved in there was Zverev, Anderson, and Isner as a kind of outlier group of big-servers. Anderson and Isner were gone a few months later though.

Musetti is currently ranked 9th but is 23rd on hard courts by Tennis Abstract’s elo rating.

TC Old Boys is a Swiss tennis club where Federer (and Bernet) started their careers.

Both technique and technology derive from the same Greek root word “tekhnē”, which roughly translates to “skill, art, or craft”.

Great stuff! I really enjoyed this breakdown of the different aspects of a swing, and how you can create something "incorrect" despite using "correct" parts.

It's a bit much to ask, but I'd like to hear your thoughts on Dimitrov's backhand. You didn't bring him up very much here, probably because his BH doesn't really hold up as well compared to other big names. What is it about the Dimitrov backhand (other than the flexed wrist at contact you mentioned in a previous post) that doesn't help his case?

Another great piece, H!

I've been reading your posts for a long time and always appreciate the level of technical insight and analytical rigor you bring. Out of curiosity, have any players or coaches ever reached out to you for consultation? Your perspective would clearly be valuable to anyone looking to refine or change aspects of their game.